OMA wilfully subverts expectations at its Glasgow Maggie’s Centre, which melts unassumingly into the background.

‘Fluorescent tube lights reflected in the shiny vinyl floor, swing doors in vomit-shaded veneer and armoured kickplates, sickly green walls and the omnipresent dado of protection hardware — protection from trolleys, wheelchairs, architecture.”

This is the language of the contemporary hospital, as described in the Architecture of Hope, Charles Jencks and Edwin Heathcote’s recent book on the Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres initiative — and one of the main motivations to start the programme in the first place.

More precisely, it is a description of a photo of a corridor in Glasgow’s Gartnavel General Hospital, within whose grounds a new £2.6 million Maggie’s Centre by OMA has just opened, funded by cancer charity Walk the Walk.

“This was our key image from the very beginning,” says project architect, Richard Hollington. “We were trying to create the antidote to the NHS corridor: something light, open, full of views out.”

He is speaking to me from Qatar, where the office has just won a vast airport project, and where several other buildings by Rem Koolhaas’ firm — for Doha’s satellite Education City — are beginning to rise out of the ground. Before Maggie’s, Hollington was masterplanning a new 70ha district for Milan’s outskirts.

Nestled into a raised, sloping site to the west of the hospital, barely legible among the trees, this little cluster of glass boxes is quite a leap of scale. It looks out upon a jumbled NHS-scape of brutish structures, from the 1970s high-rise fortress of the main hospital, to the beige-clad expanse of the Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre, built in 2007 — the second largest such facility in the UK, serving a population of 2.8 million, and the reason for locating the new Maggie’s centre here.

OMA chose a site removed from this din across a car park, retreating into a wooded slope beneath the looming Gothic facade of an abandoned institutional building. Built as the Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum in 1843, East House is now a spooky vacant shell, awaiting renovation as flats. It provides a charged backdrop to this quiet corner of the sprawling campus — detached from the world of sheds floating on the sea of tarmac below — where the centre now forms an atmospheric relationship with the Victorian pile. It shimmers like an ethereal pavilion, dropped into the grounds of the derelict manor.

This is the eighth new-build Maggie’s Centre since the first opened in 1996. Rem Koolhaas joins an all-star cast of Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Richard Rogers and Richard MacCormac — soon to be accompanied by Piers Gough, Kisho Kurokawa and Ted Cullinan, among others. Every architect is given the same brief — a light and welcoming home from home (“a home people wouldn’t have quite dared build themselves”) — yet each reinvents it in their own inimitable style.

“Each building is like an experiment in a petri dish,” says Jencks, who helped his late wife Maggie Keswick set up the cancer care centres. “They are all mini icons.”

It is as if a Case Study House has been chopped up into chunks and redeployed across the site in a scrambled cloister

The idea that each centre is the distillation of a celebrity architectural hand, a condensed trinket-treatise, has not gone uncriticised. There is a certain magpie promiscuity to the collection, in a similar vein to Rolf Fehlbaum’s Vitra campus, or Alain de Botton’s holiday homes — only ennobled by a healing agenda.

“People accuse me of saying that iconic architecture can cure cancer,” says Jencks. “We only argue that bad buildings make people feel worse — and mean that doctors don’t show up.”

As the grandfather of current-day architectural criticism, Jencks is well placed to argue the case, and to draw on an illustrious network of former students and friends to help him do it.

“It was inevitable that Rem would do one,” he says, recounting his long friendship with Koolhaas and Madelon Vriesendorp, the architect’s wife and co-founder of OMA, since they were his students at the Architectural Association in the early 1970s — along with his late wife. “We were a great foursome,” he says. “Rem was the student who didn’t understand me.”

That Koolhaas was the stubborn student is not difficult to believe, although it is particularly interesting in this context. His wilful contrarianism continues unabated: unlike most of the centres to date, Maggie’s Gartnavel bucks the trend for formal novelty and signature styling. With its low-lying orthogonal walls of blank concrete and seamless glass, the building seems determined not to join Jencks’ menagerie of mini icons.

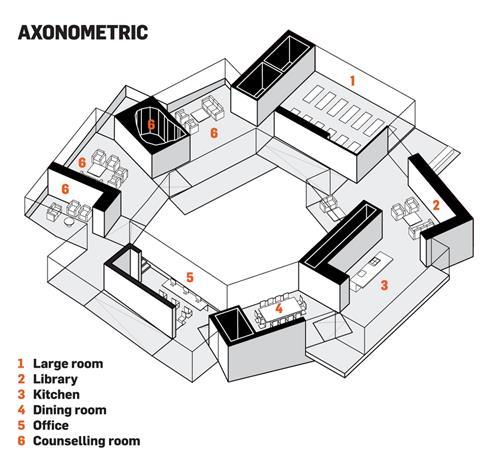

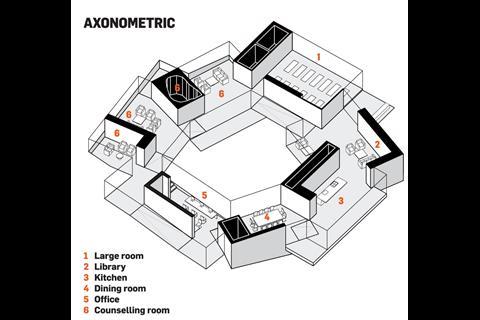

“The last thing you need as a cancer patient is to be aggressively confronted by architecture,” says Hollington, explaining that the firm wanted to make the building as “background” as possible. Its approach was thus pragmatic: the centre is disaggregated into its constituent rooms, each expressed as individual blocks, arranged in an interlocking circle around a planted courtyard, according to adjacencies of use. The more private spaces, including the three counselling rooms, are to the north, slightly submerged into the sloping site, while the public functions of kitchen, dining room and library lie to the south, open to both sides and flooded with light.

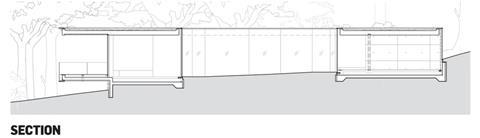

Exploiting the site’s gradient, the rooms step down to the south, via gentle ramps, and up to the north, creating different levels of intimacy through subtly changing ceiling heights. The whole structure is unified by a 350mm-deep concrete slab roof, a continuous datum that ties the building together under one plane, oversailing the facade in places to shelter small external terraces. Its depth comes from the vast spans required, cantilevering up to eight metres at points, which makes it read like a chunky, overhanging lid — earning the project cheeky comparisons with the Flintstones’ house during its development in the office.

Now built, there is little of the primitive about it. Instead, the building is expressed in the sleek, anonymous, language of classical modernism. It is a product of Koolhaas’ recent pursuit of the “generic” in architecture, the desire for “unspectacular buildings with spectacular qualities,” as OMA has called it, in a conscious rejection of the icon project.

In the office, the scheme has been run by partner Ellen van Loon — the one who knows how to build — who is also responsible for the De Rotterdam building and the forthcoming Rothschild headquarters in London, both examples of stripped, slick office blocks, referencing Mies or Yamasaki in turn, but with a knowing twist.

Glimpsed through the trees, with its full height glazing, cantilevered floors and deep, projecting soffits, the Maggie’s Centre has strong echoes of a Case Study House — as if one has been chopped up into chunks and redeployed across the site in a scrambled cloister. It is another accomplished riff on the modernist archetype — clearly of the Van Loon stable.

“It should feel like visiting the house of a friend.” says Tricia Crosbie from Maggie’s, as we step past a tree-trunk bench — a quotation from the Rotterdam Kunsthal — through the sliding glass door of the main entrance. (“If your friend lives in a John Lautner house,” I think to myself). The sleek 1950s feeling continues inside with the choice of materials, such as the planks of beech plywood, cast flush into the concrete ceiling, that follow the direction of each room (mirrored in concrete planks on the roof), and the use of full-height sliding walls that allow rooms to open up into a continuous fluid space.

It is perhaps the most open-plan of all Maggie’s Centres to date, the circuit of interlocking rooms defined only by a series of L-shaped figures, some the thickness of the wall, others swelling to incorporate shelving or services.

“We thought about it like a series of stage sets,” says Hollington. “What is the minimum you need to evoke a certain type of domestic space?”

The library is defined by a corner of timber bookshelves, the dining room by a low L-shaped bench against the wall. The kitchen — always the most important room in a Maggie’s Centre, life revolving around the welcoming cup of tea — is framed by a full-height translucent resin wall of storage cabinets, lit from a hidden rooflight to the rear. Built by resin king and long-time collaborator, Vincent de Rijk — who produced similar bookcases for OMA’s 1998 Maison à Bordeaux — the wall glows a pale blue, providing cooler north light to balance this south-facing room. In each case, extraneous parts have been eroded, the sequence of domestic spaces reading a series of deconstructed room sets.

The westernmost room, furthest from the entrance, houses the staff office. Just as open and accessible as the other areas, its

L-shaped wall is pulled back from the outer facade to provide a subtly ramped corridor — the transition space from the social, domestic world, to the more withdrawn, private sphere of counselling rooms.

It is a powerful space, entirely glazed on one side, with sliding doors leading out to a woodland landscape — designed by Harrison Stevens and Lily Jencks, Charles and Maggie’s daughter — and entirely clad in mirror-polished steel along the inner wall. Walking along the corridor, your pace is slowed by the slight gradient, there is a strange perceptual shift, as though you have been transported to the centre of the forest, with trees reflected on all sides. It is a place for pause, providing a distancing step outside on your way from public to private. It is also one of the few areas visually screened from the rest of the centre, the glazed cloister form and continually framed views allowing for little privacy in general.

Tall, generous spaces

One place you can be sure of seclusion is the loos — the brief specifies that they must be “big enough to take a chair and a bookshelf” and “private enough to have a cry”. Lined in walnut laminate, they are tall, generous spaces, although they feel a little too executive for tears.

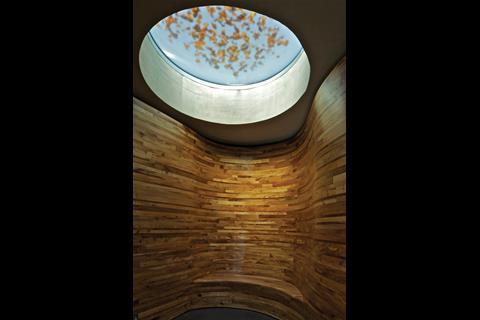

The northern edge of the building is composed of three counseling rooms, as well as a larger multi-purpose room and a tiny “womb room,” a grotto-like space of undulating elm walls, wrapped with a curvaceous bench and lit from an oculus rooflight. Produced by local furniture maker, Paul Hodgkiss, the warm, organic form provides an effective foil to the crisp, linear language of concrete and glass used elsewhere.

The other rooms are straightforward affairs, a sense of seclusion and cosiness provided by the lower ceiling heights, the fact you are semi-submerged into the landscape and the fireplaces floating in the walls. While the feeling of much of the project is positively Fosterian — immaculately poured concrete abutting frameless glazing and panellised veneer — I am reminded it is Koolhaas when the contractor points out the 6m-long timber door to the end room, which slides back to disappear into the wall — and which would require complete removal of the toilet to fix.

The brief for the loos specifies they must be ‘big enough to take a chair and a bookshelf’ and ‘private enough to have a cry’

The triumph of idea over practicality continues into the large multi-purpose room, whose entirely glazed corner walls can be slid back to open up the space to the entrance — although since they weigh half a tonne each, one might question this logic, given the weaker health of its users.

And where practicality triumphs elsewhere, aesthetics have slipped: doors used throughout the building were intended to be glass-reinforced concrete panels, but these proved too heavy to hang.

The resulting choice is a standard door blank, covered with polished plaster. It is a strange, smeary finish that jars with the in-situ concrete walls it is meant to ape.

Jencks is pragmatic about such details — not at all precious about the primacy of the architect.

“One always has to design a building twice,” he says. “Once when the architect designs it and once when the client takes control. We always have to tweak our centres when we move in — it’s a process of fine-tuning.”

He is rightfully pleased with this latest addition to the Maggie’s network. His only concern is that all the hard surfaces might be too reverberant. “We may have to put rugs on the ceiling,” he jokes.

And is he disappointed by its anti-iconic form?

“It is iconic in its minimalism,” he retorts. “It is the disappearing icon!”

This is, of course, true. Although, I can’t help but think that there are other architects who do well-detailed minimalism on this small scale — the “generic” archetypal villa — better than a practice that is more concerned with bigger, rhetorical questions.

Project team

Architect OMA, Client Maggie Keswick Jencks Cancer Caring Centres Trust, Implementation architects Keppie, Structure Sinclair Knight Merz, Services KJ Tait Engineers, Landscape Lily Jencks, HarrisonStevens Fixed shelves Vincent de Rijk

2 Readers' comments