Rehabilitation rates could be improved by better design, says RIBA-backed report

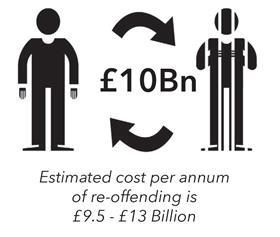

Reoffending rates could be cut and the welfare of prisoners and staff improved if some simple design measures were adopted in the next generation of jails, according to the authors of a new report.

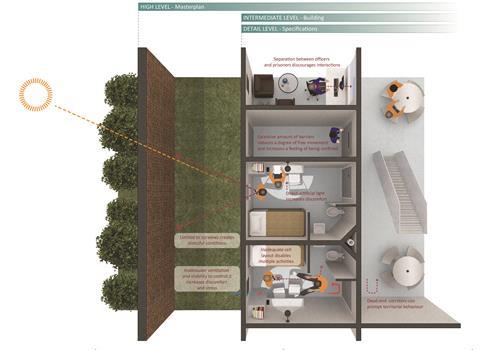

It argues that the way in which prisons have been commissioned and built in the past has been a barrier to rehabilitation and the welfare of the workforce.

Putting full-length windows in cells to give prisoners views of greenery, doing away with long, straight corridors, using timber doors and softening lighting are among the recommendations.

Wellbeing in Prison Design was written by Matter Architecture co-founder Roland Karthaus with environmental psychologist Lily Bernheimer and prison experts in consultation with the Ministry of Justice prison estate transformation programme. It was funded by the RIBA and Innovate UK.

It suggests independent design review should be part of the planning process and that modern construction methods should be explored.

It says layouts should be designed to encourage positive interactions and relationship building, with fences, gates and bars excluded wherever they are unnecessary.

Habitable spaces should have views of nature or over the prison walls and outside spaces should be cultivated, it says, along with recommendations on acoustics and ventilation.

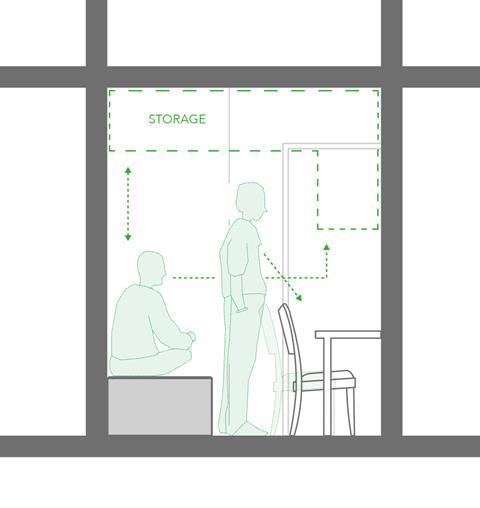

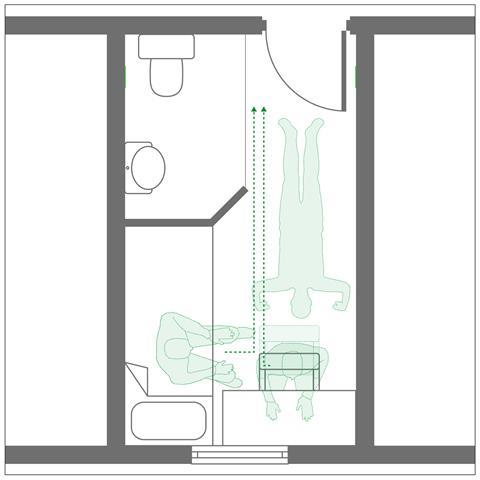

At a more detailed level, it says cells should be personalisable, be configured to allow prisoners to do press-ups, and have full-length windows. Long corridors should be staggered because distances above 20m reduce facial recognition, increasing dissociation between people. The proposals would reduce tensions, diminish the institutional effects of repetition and also let in more light.

Karthaus, who set up Matter in 2016 with Jonathan McDowell, formerly of McDowell & Benedetti, said: “There is currently a great appetite for change both within and outside the prison service. Good design is about problem-solving and the conditions in prisons for staff and prisoners and the consequential rates of re-offending represent a major problem that design can help to solve. Our report sets out design guidance that aims to do just that.

“The staff and prisoners we spoke to were very clear about some of the – often relatively small – practical changes that could be made to ensure prison buildings play their part in creating more rehabilitative environments: from making visitors spaces welcoming and child friendly, to ensuring that light and heating systems create a good work environment.

“Prison buildings cannot on their own turn people’s lives around but by using the latest building techniques and improving the way people use the interior and exterior spaces, they can support wider culture change.”

A tale of two prisons

By Roland Karthaus

HMP Low Moss, designed by Architects Holmes Miller, is possibly the best example of prison architecture to date in the UK – the public face of the building has a civic presence and is designed to appear accessible and welcoming to visitors, with careful exterior landscaping. Facilities within the prison have good daylighting and are colourful, with an atmosphere much like a good further education college. Full-height glazing in many areas without bars has a very positive effect. The houseblocks, however, are similar to many other prisons and the deeper one travels into the prison the more conventional and security-prioritised it becomes. The external spaces are also poorly laid out and designed. The budget for this prison is understood to be higher than usual.

HMP Berwyn, pictured below, is the prison that our team worked with to survey building user experience (staff and men in custody). It is brand new and the UK’s largest prison. Originally designed as a high-security prison, it is operated as low-security (category C) meaning that many aspects of the building design are overly secure and therefore less supportive to rehabilitation. The governor has made a public commitment to a rehabilitation culture, however, and has decorated the prison with inspirational images, colours and other measures. Each man in custody has a laptop connected to an internal network for ordering clothing, choosing meals and accessing educational material. Our survey was delivered via this system. Those in custody are not called prisoners, but simply “men” and officers are expected to knock before entering cells. The men we interviewed said it felt like no other prison.

Both of these examples illustrate how environments can be adapted to better support rehabilitation, but both are still underpinned by a set of conventions for prison design that have barely changed over the past half a century (and in some cases more). Our guidance looks beyond this to see what further changes can be made, based on the evidence that they will support health and wellbeing and therefore rehabilitation.

2 Readers' comments