Ben Flatman speaks to Jas Bhalla – architect, planner and founder of Jas Bhalla Works – about building a practice rooted in long-term thinking, the value of diverse routes into the profession and the challenge of delivering on the UK’s housing ambitions

Nine months into its first term, the Labour government remains under pressure to prove it can meet its flagship pledge: the delivery of 1.5 million new homes over five years. Planning applications are at historic lows and, despite a string of policy reforms, the housing pipeline remains stubbornly slow to pick up.

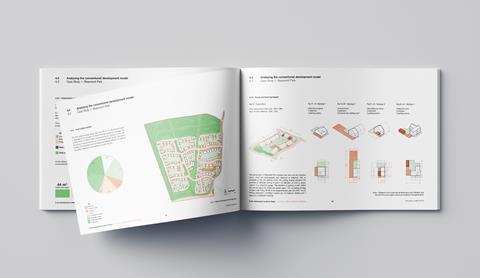

The scale of the task is compounded by the lessons of history. Previous bursts of rapid housebuilding left behind mixed legacies. Poor public realm, car dependency and inadequate social infrastructure have been recurring themes when design has taken a back seat to numbers. A key question now is whether the current housebuilding drive can avoid repeating those mistakes.

For Jas Bhalla, an architect and planner who leads Jas Bhalla Works, the stakes are clear. His training spans both disciplines – planning at the Bartlett, architecture at Yale – and his current work includes private houses, major settlements and public realm-led urban strategies.

“We are not architects who are interested in masterplanning,” he says. “We are planners who also do architecture.”

Bhalla’s practice has carved out a role at the intersection of urban strategy and design, working on new communities and infill housing, and advising public authorities on how to unlock complex sites. A cross-disciplinary perspective, he argues, offers a more rigorous and responsive approach.

“The synthesis of architecture, urban design and planning … means we’re a lot more rigorous when it comes to analysis and research,” he says. “We don’t come with a fixed idea … we try to learn from place – and that can be political, historic, physical or client-led.”

Falling into planning – and staying with it

At school, Bhalla had aspired to become an architect but, with no contacts in the profession and a daunting sense of the long years of training, he turned instead to a planning degree at the Bartlett. “I kind of accidentally fell into planning,” he recalls.

“I wanted to be an architect originally … but I didn’t understand why it took so long. It’s massively ironic now, considering how long I’ve spent in education.”

What began as a pragmatic choice soon became a passion. “To be honest, I really enjoyed it,” Bhalla says. “I think planning’s a brilliant base degree because you get to learn a bit about economics, sociology, history, theory. It’s a really good way of getting to know the built environment.”

Bhalla’s early career coincided with the final years of the last Labour government. He joined Urban Practitioners, a planning and regeneration consultancy that would later become part of Allies and Morrison. There, he found himself working on large-scale public sector masterplans. But the financial crisis of 2008 changed the landscape.

“When we had the crash … all of those ambitious public sector projects just got kiboshed,” he says. “I made the decision then that this isn’t going to be a couple of weeks’ blip – it’s going to be longer.”

He applied for and won a Fulbright scholarship, heading to Yale for a postgraduate architecture degree. The move would reshape his trajectory, but his grounding in planning – and the experience of a more interventionist moment in UK regeneration policy – left a lasting mark.

Yale, Adjaye, and the long road to qualification

At Yale, Bhalla found himself in a context of abundant resources, intellectual diversity and global peer networks. “It was an amazing experience,” Bhalla says. “They were really formative years.”

One of his studio tutors was David Adjaye and, after graduation, Bhalla briefly joined Adjaye Associates in London. “I enjoyed studying under him,” he says. But the transition from academic to professional life came with a reality check.

“Working with the practice was a bit more challenging in terms of hours … they did very interesting projects, but it was quite gruelling.”

He later joined KPF in London, where a different culture took hold. “The practice was very forward-thinking in terms of processes and technology,” he says. “Its embrace of digital innovation was inspiring. All of those things have really had an influence on the practice I’ve set up.”

Returning to the UK, Bhalla faced another hurdle. Despite three years at Yale and a master’s degree in architecture, he found himself back at square one within the UK’s rigid qualification framework. To achieve ARB registration, he had to piece together the system’s full sequence – part 1, part 2 and part 3 – simultaneously, across three different institutions.

“It’s a completely ridiculous system,” he says. “I was going to Birmingham one day a week to collect my part 1 … while I was also doing my part 3 in the evenings at London Met.”

Yet the determination to persist reflects a deeper commitment to opening up access to the profession. Asked what he thinks of ARB’s on-going education reforms, which will effectively remove the requirement for part 1 by 2027, he says: “I’m a strong advocate for changing routes to qualification … whenever anyone asks me to give an opinion or reflect on that, I’m happy to support what ARB are doing.”

Starting up in uncertain times

In 2018, Bhalla founded his own practice. What followed, in his words, was “a bumpy ride”. Brexit, the pandemic, inflation and a sluggish post-covid economy have all shaped the landscape in which Jas Bhalla Works has taken root.

But, rather than stall the practice, those pressures helped to define its ethos. “We’ve grown in that context,” he reflects. “It’s something I’m really proud of – that we’ve been able to survive and then thrive.”

The past year has been a turning point. “We rebranded, grew and moved last year, with Vicky joining me as a director. It’s been a big milestone having her come on board.”

Vicky Payne, an experienced urban designer and strategic planner, now leads on the practice’s larger-scale masterplanning projects, building on her previous roles at URBED and the Quality of Life Foundation. Alongside this growth, the studio has doubled down on creating a healthy working culture.

“We are doing our best to make the studio a good place to work,” Bhalla says, “by having things like a nine-day fortnight and giving the team access to a variety of projects.” It reflects a broader ethos; one that values rigour and ambition, but also balance and breadth.

Working at multiple scales

“We’ve intentionally set out to work at different scales and on different types of projects,” Bhalla explains, citing the value of “cross-pollination” between large-scale settlements and small, highly site-specific commissions.

The practice’s work ranges from private house commissions to unlocking constrained council-owned infill sites in north London, through to developing visions for new towns of 5,000 homes in the east of England. “We’re always asking: how can we take the lessons learnt from one project and expand them across the portfolio?” says Bhalla.

“What’s the bigger picture and narrative for what we are doing in this specific location?”

That willingness to shift between scales has proven both strategically and intellectually fruitful. The firm’s work on major strategic sites has directly informed its more granular projects – and vice versa.

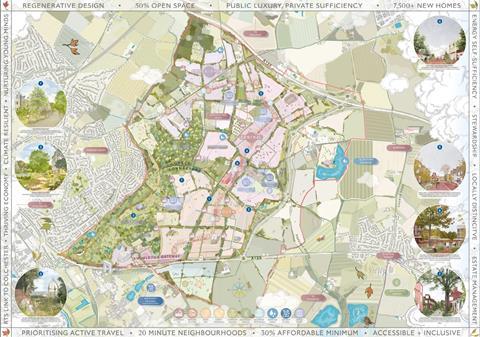

Bhalla points to the firm’s experience supporting Latimer and Clarion’s 7,500-home Tendring-Colchester Borders garden community in Essex, and recent collaboration with dRMM on the smaller-scale Aylesham Centre redevelopment in Peckham, south-east London. Both, he says, are grounded in a shared interest in the early establishment of amenities, place identity and long-term flexibility.

A new generation of new towns

As well as Tendring-Colchester Borders, the practice is also currently working on other significant new settlement projects, including Sibson Garden Community, which is a proposal for 4,500 homes just outside Peterborough. These are projects that seek to redefine what a new town can be in the 2020s.

For Bhalla, the central challenge is less about density or house types than about how to generate a sense of place from the outset. “How do you make these developments feel like real places from day one?” he asks.

“You’re creating a community that often doesn’t currently exist – that means front-loading amenity, walkability and the conditions for social and economic life.”

It also requires careful attention to urban grain – and a deliberate move away from formulaic approaches to settlement planning. “Enduring masterplans need to cohere at different scales,” , Bhalla explains.

“They need to work at a strategic level in terms of their economic offer and connectivity, but they also need be made up of buildings, streets and open spaces where people want to come together, where social life can thrive.”

Rather than separating uses or applying generic templates, the practice works to embed active travel, flexibility and distinctiveness early in the process. That includes space for independent retail, clear civic markers and the small-scale decisions that help new places to feel coherent from the start.

The Tendring-Colchester scheme, which Bhalla’s studio is delivering in collaboration with Haworth Tompkins, Bell Phillips, Periscope, HAT and Stantec among others, includes 25 hectares of green and blue infrastructure and is intended to be a walkable extension to the urban edge, linked by a new rapid transit service. But the scale of ambition inevitably brings risk.

“There is a kind of uncertainty that comes with large-scale development,” he explains. “You’re working with delivery horizons of 20 years or more … so you’re always trying to anticipate how to phase things, how to build enough confidence in a place that people want to move there before the full offer exists.”

It is a marked contrast from the way housing is often delivered – as a one-off, fully packaged product. “Most architectural projects finish when they’re built,” Bhalla notes. “With new towns, that’s just the beginning.”

The practice’s role is part design team, part strategist – helping local authorities and landowners to work out how to shape, seed and sustain urban life.

Past failures weigh heavily: sterile dormitory towns, under-served estates, infrastructure that arrives too late. Bhalla sees design as a tool for unlocking social and economic value early in the process.

“People underestimate how important that early planning is,” he says. “It’s not just about how you organise space – it’s about how you create the conditions for something real to grow.”

Density, transport and the British preference for houses

Delivering dense, pedestrian and cycle-friendly urbanism in the UK remains one of the biggest barriers to creating sustainable transport systems. Bhalla argues that this is, in part, due to the country’s failure to take a strategic, region-wide approach to allocating growth.

“The first design decision you make is where you’re going to build, and what you’re going to allocate for what densities and what type of homes,” he says. “We’ve forgotten the art to that.”

Without this upfront coordination, density rarely arrives in the right places to support viable public transport. Bhalla points out that London is the exception, not the rule, when it comes to mass transit. “London by UK standards is amazingly well connected. Compared to the rest of the UK, it’s incredible.”

But he acknowledges that it is a model not easily replicated in areas where infrastructure investment is patchy. He welcomes tentative signs that the government is reviving regional spatial strategies but stresses that delivery must follow rhetoric.

Cultural preferences also present a structural challenge. Bhalla is realistic about the deep-rooted appeal of suburban housing in the UK. “People don’t have the same relationship with apartment living that they do in parts of continental Europe. Everybody wants a garden and a house,” he says.

While his practice is exploring models like walk-up maisonettes and low-rise apartment blocks, he acknowledges that selling flats in out-of-town schemes remains difficult unless they form a modest proportion of the mix. “Most schemes where you’ve got lots of apartments – and I say lots, above 40% – you will struggle to sell them,” he explains.

Instead, he advocates for gradual, phased density that grows with place identity and amenity provision. “Once you’ve got some momentum behind the place that you’re trying to build,” he says, higher densities can be more viable.

On Ilford, retrofit, and town-centre intensification

Bhalla’s ongoing work in Ilford, where he was appointed town architect in 2022, offers a different kind of design challenge. Situated on the Elizabeth Line and part of the wider growth area for east London, the town centre presents clear opportunities for densification. But realising that potential is far from straightforward.

“It’s a really interesting place to work,” Bhalla says. “It has great infrastructure, it’s incredibly diverse, it’s got amazing food, but it’s also incredibly complicated – you’ve got multiple landowners, fragmented sites, low sales values … It’s really hard to unlock.”

The challenge, he suggests, is not so much the planning bureaucracy as economic viability. “It’s not the planning department that’s holding up delivery,” he says. “It’s not an obstruction issue – it’s a viability issue.”

The situation in Ilford speaks to a wider structural concern in Bhalla’s thinking: that the constraints affecting town-centre regeneration are shifting. As new fire safety rules, staircase mandates and energy regulations come into force, he warns that certain building types – especially mid-rise, mixed-use housing – are being rendered commercially unviable.

Bhalla singles out the two-staircase requirement as an example of policy that may be well intentioned, but which risks unintended spatial and financial consequences. In areas such as Ilford, where land values remain relatively low and existing buildings are underperforming, even small shifts in policy can decisively tip the balance.

“I worry that we’re going to lose a generation of mid-rise housing in the name of safety, but not necessarily get better buildings as a result,” he says.

On Labour, policy, and the limits of reform

Bhalla is cautiously optimistic about the Labour government’s first nine months in office. He credits ministers with restoring a sense of ambition to housing and planning policy, and supports key elements of their agenda – not least the tentative return of strategic planning and the push for local authorities to undertake green belt reviews.

But he also warns that ambition alone will not be enough to bridge the widening gap between aspiration and delivery. “There’s been a lot of good rhetoric and a lot of good ideas,” he says. “The challenge is that they inherited very much a declining market in terms of the number of new homes.”

The broader economic context has only sharpened the challenge. “The government has underestimated just how challenging the environment is,” he says, pointing to persistently high interest rates, weak market confidence and the compounding effects of recent regulatory changes. “They’re really putting their foot on the accelerator when it comes to planning policy changes, but at the same time … the high-risk buildings gateway process and other regulations are acting as a brake.”

While Bhalla sees merit in Labour’s emphasis on long-term reform, he warns that it risks obscuring the need for urgent delivery. “We’ve got this long-term ambition, but at the same time you’ve got short-term stagnation in the market,” he says. “The 1.5 million homes target looks more and more challenging with every month that passes.”

He is particularly sceptical of any over-reliance on new settlements. “There is an allure to drawing a new place on a map,” he says. “But we’re kidding ourselves if we think these will deliver homes immediately.”

Instead, he advocates for renewed focus on unlocking sites in existing cities – particularly regional centres that have struggled in recent years. “I don’t think you have to choose between new towns and cities,” he says. “But I do think we’ve lost sight of the importance of urban reinvestment.”

What next? Thinking long-term in a short-term world

If there is a thread that runs through the practice’s work, it is a commitment to long-term thinking in a system that rarely rewards it – whether envisioning new settlements that may take decades to mature, or guiding town centres through incremental change.

“The reality is that the way in which we commission, the way in which we construct projects, the way in which we think about budgets – it doesn’t allow us to engage with the level of complexity that these sorts of projects require,” he says.

Bhalla does not claim to have all the answers. But his approach – analytical, context-led, deliberately hybrid – offers one model for how architects and planners might engage more deeply with the systems they work within. He speaks of “trying to build a body of work that connects ideas across different scales”, of linking the “micro and macro” in ways that are as politically literate as they are spatially ambitious.

What sets Bhalla apart is his refusal to treat design as an isolated discipline. He approaches housing, infrastructure and placemaking not as technical exercises, but as questions about power, legacy and how society is organised.

His work is driven by a desire to understand – not just what should be built, but why, for whom, and to what end. “I don’t want to be a generalist practice,” he says. “But I want to be able to speak confidently across the big things and the small things.”

This, perhaps, is where Bhalla’s contribution is most distinctive. In an era shaped by climate urgency, political volatility and mounting housing need, he is building a practice designed to navigate complexity – not simplify it. Not by offering slogans or simple solutions, but by asking the harder, more systemic questions that the industry too often leaves unspoken.

>> Also read: Jan Kattein: architect as catalyst – ‘A transformational impact can be achieved with limited means’

>> Also read: Material Cultures: the radical architects rethinking how – and what – we build

1 Readers' comment