A new book by Nigel Green and Robin Wilson offers a fresh perspective on the significance of French brutalism, writes Jacob Paskins

Many of the Paris Olympic events this summer will take place in the Seine-Saint-Denis, Hauts-de-Seine and Yvelines departments, which means spectators will venture beyond the boulevard périphérique that separates Paris from its surrounding region. The Paris-centric media has long dismissed the highly populated banlieue as a place devoid of interest, so it seems fitting that the suburban towns are getting some of the attention and investment they deserve. Away from the sport, the greater Paris region has a rich architectural legacy that should be better known.

Brutalist Paris is an ideal companion to discover innovative mid-twentieth century architecture of the region. This compact volume, designed to accompany the authors’ Brutalist Paris map (2017), introduces over fifty buildings from the 1950s to 1980s through photographic portfolios and seven short but probing essays. Although some familiar names appear – Le Corbusier, Niemeyer, Chemetov – much of the focus is on architects who are less well-known outside of France, such as Renée Gailhoustet, Jean Renaudie and Nina Schuch.

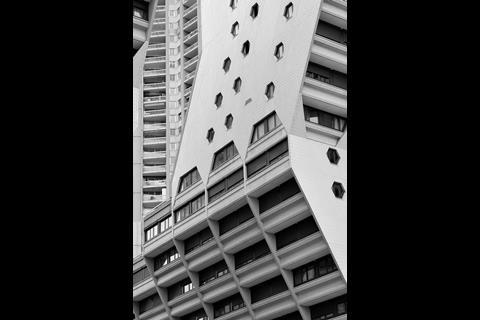

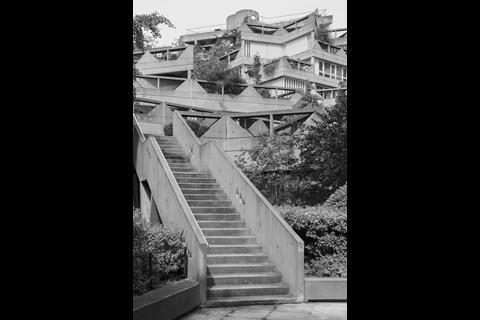

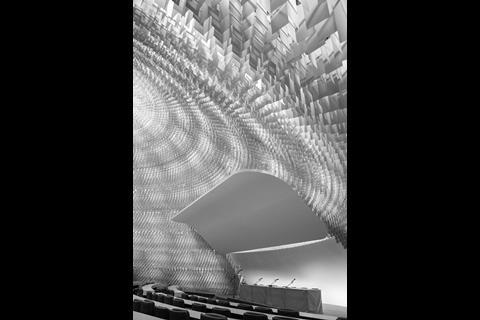

The photographs offer perceptive insights into the architecture, often emphasising tightly cropped details over expansive views of buildings within their urban context. This choice of framing, along with the consistent use of monochrome photography, emphasises the texture and materiality of the predominantly concrete architecture featured. One disadvantage of the monochrome images is they tend to make all surfaces to appear similar in colour, yet, as the book acknowledges, brutalist architecture comes in an almost infinite variety of tones and finishes, and some of the key sites in the book are strikingly polychromatic, such as the Orgues de Flandres estate in the nineteenth arrondissement or Les Nuages in Nanterre, which is worth visiting now to see the original colourful mosaic cladding before the estate is redeveloped and the towers reclad in stainless steel.

The book is produced by Photolanguage, a collaborative art practice between photographer Nigel Green and architectural historical Robin Wilson. The authors are suitably qualified guides to the lesser-known architectural sites of the Paris region having spent the last 25 years exhibiting and publishing work that draws attention to marginalised urban sites, including Calais and English coastal towns. Brutalist Paris differs from most commercial publications on brutalism as its photography is not simply an illustration but part of a dialogue between text and image to suggest new ways of knowing the city.

The book’s image captions combine the views of contemporary critics with the authors’ own subjective responses to the site. Some captions draw out surprising details in the photographs, raising awareness of the material diversity and formal inventiveness of French brutalism, while other captions are more cryptic and only start to make sense when cross-referenced with one of the essays. The result is an active dialogue between text and image, which, the authors argue, might generate a fresh way of understanding these buildings in person.

Each of Wilson’s essays grapples with brutalism as a category of both architecture and critique, especially in the French context. Until the recent popularisation and reappraisal of brutalist architecture, few architects consciously accepted the label of brutalism to describe their work, as the word was more often used as a term of abuse. Despite the widespread construction in France of what we today recognise as brutalist architecture, and the French etymology of the word, French architects and journalists rarely spoke of brutalism until the early 21st century. Unlike the widespread use of the term in Britain since Reyner Banham’s founding texts on brutalism in the 1950s, the first reference to brutalist architecture in Le Monde newspaper was only in 1980.

Brutalist Paris is much more than a mapping project and a showcase of fashionable concrete buildings; it proposes new theoretical insights into brutalist architecture. Wilson values Banham’s original characterisation of brutalism to help define examples in the Parisian context, in particular the emphasis on structural legibility, clarity of spatial organisation, memorability of image, and an acceptance of the ‘as found’ characteristics of materials and construction processes.

In one essay Wilson emphasises the ‘performative expression’ at play at the UNESCO conference hall, in which the rain guttering is dramatised to such an extent that it becomes the principal subject of the design. Another essay considers how the availability and quality of labour affected the construction of brutalist architecture. At Les Bleuets, a housing scheme in Créteil, the clumsy finish of unskilled labour is turned into witty caricature by emphasising the ‘artifice’ of the chunky stone set into the concrete panels, creating a striking visual identity for the estate.

Wilson also moves beyond Banham’s framework to propose specific attributes of French brutalism, including an element of surrealism. He argues that French brutalism was a ‘critical architecture’ in a period of crisis marked by political upheaval, rapid urbanisation, housing shortages and the legacy of poorly conceived suburban housing estates in the 1950s and 60s.

The book argues that the most valuable contribution of Parisian brutalism was in its search for new urban forms and housing configurations. Significantly, a number of brutalist projects rejected tower block or horizontal bar typologies that dominated much post-war development. Wilson notes that the often-negative media coverage of the banlieue overlooks the fact that many brutalist urban schemes emphasised place-making opportunities to build community through the design of innovative public spaces.

The book draws attention to the domestic and social potential of brutalism as seen in the projects for Ivry-sur-Seine by Gailhoustet and Renaudie in the 1970s. The low-rise high-density mixed development of housing, commercial and public space of the Jeanne Hachette Complex created a new star-shaped urban typology that rejected earlier forms of public housing. This provides a sense of individual housing with private outdoor terraces while also retaining a dense urban ensemble. The focus on pedestrian communal spaces and proximity to the street marked a distinct move away from the isolated suburban estates of the 1950s and 60s.

The work of Gailhoustet, Renaudie and Schuch promised a new model of mass housing within existing towns that might help reinvigorate urban community and participation. The social commitment in these projects – at a theoretical level at least – is a stark contrast to the popular perception of brutalist architecture as rundown shopping centres and neglected car parks. Municipal authorities and developers, however, quickly turned their backs on the unconventional angular forms of this late brutalist architecture, and these prototypes have been dismissed in favour of a return to more standardised housing blocks that rarely consider the provision of public space.

Brutalist Paris also considers sites that have been repurposed in recent years following abandonment or disrepair, such as Pantin Dance Centre and a former office building that has been converted into housing – these are important case studies for renovating seemingly difficult to convert brutalist buildings and a more sustainable alternative to demolition. This is particularly pertinent as a number of other sites featured in the book are currently abandoned or are earmarked for demolition, or have been insensitively renovated either by recladding or by closing off public spaces.

Brutalist Paris makes a valuable contribution to identifying neglected projects that still have much to inform contemporary questions about the design of mass housing and the repurposing of abandoned brutalist structures. The book is more focused on the legacy and future of brutalist sites, so readers who want to learn more about the historical, social and political context of Parisian brutalism will need to look elsewhere.

The book notes that communist-run town of Ivry sponsored innovative urban developments, and the French Communist Party commissioned Niemeyer to design their Paris HQ. However, this certainly did not mean that French brutalism was an inherently socialist form of architecture, after all, the brutalist Prefecture buildings of Bobigny, Créteil and Nanterre were prominent symbols of the Gaullist state.

Brutalist Paris could offer a more historically grounded account of brutalism by acknowledging further the political and social circumstances of urban development in the Paris region. Nevertheless, anyone with an interest in post-war architecture will want to use this book to guide them through the Paris region. Brutalist Paris reminds us that Paris of the future has long existed on the other side of the périphérique – go see its brutalist legacy before it disappears.

>> Also read: Brutalism - Where did it all go wrong?

Postscript

Brutalist Paris by Nigel Green and Robin Wilson is published by Blue Crow Media, 2023.

Jacob Paskins is an Associate Professor in the Department of History of Art, University College London, and author of Paris Under Construction: Building Sites and Urban Transformation in the 1960s, published by Routledge.

No comments yet