Edmund Fowles reviews the first volume of Caruso St John’s collected works

In an age defined by digital technology and the abundance of the image, accessing architects’ work has never been easier, so what can architects’ monographs offer today?

Historically, monographs were retrospective catalogues, compiling a practice’s ‘oeuvre complète’, often gathering disparate work into a tidy chronology of buildings and, occasionally, unbuilt projects. The work would usually be preceded by a contemporary commentary, but rarely by revelatory criticism. Even so, they were of considerable value to architects and historians in the pre-digital age who sought elaboration of the architect’s intent and technical insight through previously unobtainable drawings and details, much of which we can now access in real-time.

In an insightful discussion for Quaderns, in 2019, Adam Caruso concedes: ”I try to avoid it but if you accidentally sleepwalk into Dezeen, you flip through the stuff and there’s simply too much information”. Tellingly, Peter St John emphasises the importance of ”a particular way of photographing things”, recalling an early Herzog and de Meuron monograph that left a lasting impression; each project represented compellingly by just two images.

We are given the space to look long and hard, and the tools to decipher the meaning in the work

Jean Baudrillard critiqued the rapidly increasing prevalence of the image in contemporary culture in his 1981 Simulacra and Simulation: “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.” It is a condition all too familiar, in our image laden society. Confronted with an endless wallpaper of content, it becomes hard to decipher any specific and resonant meaning at all.

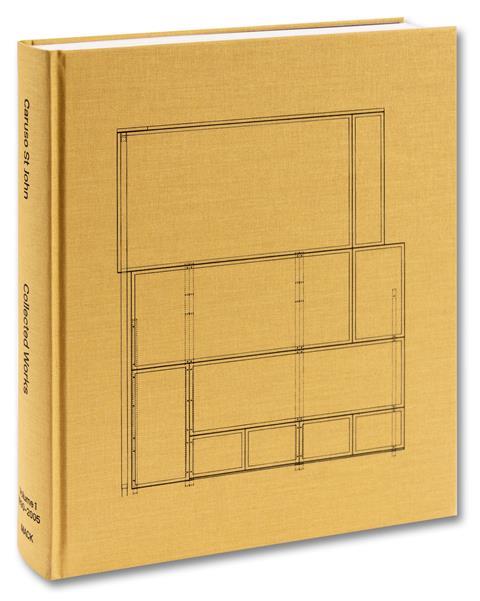

Caruso St John’s ‘Collected Works: Volume 1 1990-2005’ offers a powerful counterpoint to this current predicament, an insightful journey through a pivotal period in British architecture and a refreshing stance on the role of the architectural monograph today. It reminds readers of the subtle intensity that a pairing or grouping of photographs and drawings, in relation to white space or texts, may have in eliciting ideas. We are given the space to look long and hard, and the tools to decipher the meaning in the work.

The approach taken to structuring this substantial volume is qualified within the preface as ”intentionally diverse”, not trying to be complete or systematic, but attempting to ”defuse the tendency of monographs to gloss over the uncertainty and ambiguity that lie at the root of all architectural practice”.

Spanning the practice’s first 15 years and organised thematically rather than chronologically, the work is gathered beneath a range of headings, such as Early Works and Early Competitions, Poetic Realism, Lewerentz and Contemporary Art. There are texts by, and about, the practice, lectures and interviews, reference texts and “images that spent a lot of time on our table”.

The resulting collection of material may at first glance give the impression of being loosely collaged, but a few pages in you realise the care and precision of the editing that has led to the arrangement. The practice has designed some 50 exhibitions and their breadth of experience in handling diverse material is clearly evident here.

The opening text, The Presence of Construction, is a transcript from an AA lecture delivered by Caruso and St John in 1998 and it establishes many of the threads of enquiry that weave through the book, re-emerging periodically as ideas in built work, in references, photographs and conversations. This text reveals an attitude to history quite distinct from the prevailing architectural climate of the 90s, still ripe with the promises of high-tech and the potential delusions of digital, generative methods of design. The architects express a disdain for ‘the new’ and their preoccupation with the physical nature of construction.

The early works are lean, at times rough assemblages of old and new, built with modest means

Distinct from more formal monographs, this book is perhaps more akin to a critical thesis, or even a manifesto. It explores, develops and reasserts the architects’ ideas in varying mediums and through a chorus of voices: critics, clients and artists.

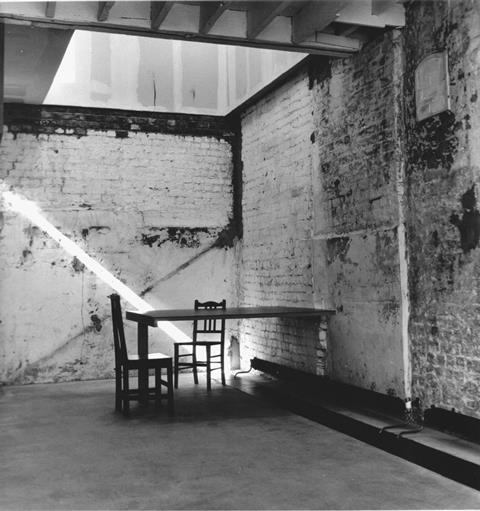

Their experimentation with construction is most directly explored through a handful of modest early projects. Here, we gain an insightful glimpse of the two young architects’ attempts to translate conceptual ideas, into built form. They reveal themselves, for example, in the tautness of brickwork wrapping their first newbuild house in Fishtoff, windows set flush to the brick, a reference to their enduring interest in Sigurd Lewerentz, to whom a chapter is dedicated.

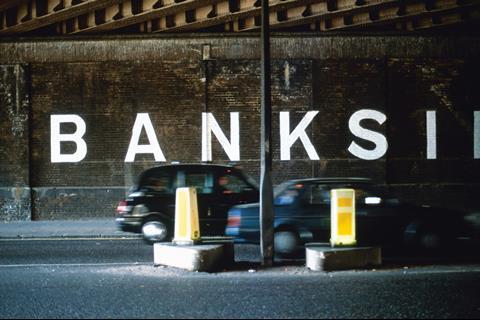

The early works are lean, at times rough assemblages of old and new, built with modest means. The inclusion of previously unseen material, such as St John’s own house at Orelston Mews, contextualises the reader, offering an illuminating perspective of London in the late 1980’s and shedding light on both the physical and economic conditions that met Caruso’s and St John’s nascent practice in the shadow of economic recession. The current recession brings added relevance to the reading of the austerity embodied in these early works.

Despite its challenges London, then, served as nourishing ground for architects with an emerging interest in working with what is found. Asked in one interview about the ideal site, St John replies: ”There is no such thing as a bad site, you just add”. That idea is developed poetically in a conversation between Hans Kollhoff and Wim Wenders, reflecting on the decaying Berlin of the 80s, Wender’s suggests ”…the ‘broken’ burrows deeper into the memory than the ‘whole’. The ‘broken’ has a kind of brittle surface that memory can latch onto. On the clean surface of the ‘whole’, memory slips away”.

Somewhere between these carefully positioned meditations and the architects own contributions, such as The Tyranny of the New and London for Instance, a broad and complex understanding of the architects’ sensibility towards history emerges. This is the belief that the contemporary world is composed not solely of the new but of everything that has come before.

Caruso goes on to reference T.S. Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent and explains how Eliot ”insists on the fundamental importance of cultural continuity in the production of new work, and warns that the artist must engage with the historical breadth of a discipline…” This idea is pursued through a spectrum of built work, perhaps most compellingly with Walsall New Art Gallery, in its oscillation between familiarity and contemporaneity, and between the domestic and civic.

However, I was left wanting to learn more about the difficult moments

The monograph’s more poetic and theoretical discourses are balanced by a series of short, first-person commentaries accompanying each project. These revealing passages give enjoyable insights and have a more personal, autobiographical quality, shedding light on how early projects came about, their introduction to key reference works, or the pretext to their involvements with their first arts clients.

At times it brings humility, as St John notes during the making of his own house at Orleston Mews: “I didn’t know how to do good details”’. At other times, disappointments are revealed, such as losing the competition for the Architecture Foundation headquarters to “an inexplicable and unbuilt project by Zaha Hadid”.

This parallel narration brings a cohesive structure to the book, guiding readers through a breadth of work, linking the diverse themes and concepts with references and buildings. However, I was left wanting to learn more about the difficult moments. It is Rowan Moore’s essay A Pebble on Water about the Walsall New Art Gallery that offers the greatest glimpse of the hard reality of delivery, elegantly capturing the delicate alignments that enabled this ambitious project to proceed despite perilous funding challenges, rising costs and extension of time claims.

Until this account of the turbulent birth at Walsall, there is an unsettling impression that all the projects breezed their way into existence, which of course is never the case. Moore’s openness to the challenges of this process lends further merit to the extraordinary achievement of delivering Walsall New Art Gallery, and by association, to the broad and impressive catalogue of work encompassed by Collected Works.

Ultimately, this is a generously ‘open’ book which can be accessed at many levels: as a point of reference to a single project, a brief chronology if following the narrative project summaries, or a total immersion into the constellation of culture, memory, construction and emotion that Caruso St John’s architecture inhabits. Perhaps the book’s greatest triumph is the subtle interplay between written contributions, photography, drawings and references. Meaning gently surfaces in the shadows between words and images, bringing new revelations and distinguishing Collected Works as an important contribution and provocation to the architecture monograph format.

The book’s organisation echoes the architects’ view of history, not as a tidy, sequential procession of events but the presence of all history, all at once. Though it contains writing, images, drawings, buildings, some produced over 30 years ago, it successfully eludes the definition of being retrospective. Its content demands to be understood and evaluated not just in the context of its period of production but against the simultaneity of history and the present. In this sense, the ideas and work contained could be considered timeless.

Postscript

Collected Works: Volume 1 1990-2005 by Caruso St John is published by MACK Books

Edmund Fowles is director of Feilden Fowles Architects

No comments yet