As urgent demands for reuse and sustainability transform the priorities of contemporary architecture, Mary Richardson explores how conservation architect Donald Insall Associates – long champions of repair and adaptation – is building on its pioneering legacy to meet the needs of a changing world

In recent years, conservation architecture has moved from the margins to the mainstream. As the need to reuse and adapt existing buildings becomes ever more urgent in the face of the climate emergency, practices with deep expertise in historic fabric are increasingly at the centre of architectural debate. Few firms are as closely associated with the evolution of conservation practice in the UK as Donald Insall Associates.

Founded in 1958 by Sir Donald Insall, the practice helped to shape modern approaches to heritage management at a time when historic buildings were widely seen as impediments to progress rather than assets to be reused. Today, as the profession grapples with balancing heritage, sustainability and contemporary use, the questions that have long been core to Insall’s work have never felt more relevant.

Now employing 140 staff across eight studios, the practice is seeking to honour its past while rethinking its role for a new era. Under the leadership of chief executive Dorian Proudfoot and director emeritus Tanvir Hasan, it is aiming to carry forward its founder’s ethos while addressing the challenges of the contemporary built environment.

A love for old buildings

When they talk about their shared passion for old buildings, Proudfoot and Hasan’s enthusiasm is immediately evident. “What fascinates me most about historic buildings is the memories and the stories, and that authenticity of the fabric,” says Proudfoot.

“You can imagine all the stories that have happened, and that just makes it so much more appealing and of greater depth than a modern building. For me, they do not even compare.”

The connection is personal as well as professional for Proudfoot. “I was born in a vernacular listed cottage in the Chilterns, with beams and old floors – really old – and it’s that kind of authenticity that appeals to me,” he recalls. “You just feel comfortable in an old building because it’s as if it’s got the seal of approval of so many generations.”

He spent school holidays accompanying his father, a stonemason, to National Trust properties. “I would knock around the grounds while he worked and, from very early on, I knew I wanted to work in that kind of environment.”

Hasan’s path into conservation was shaped by a different but equally powerful set of experiences. “I was born in Pakistan though I have spent most of my life in Egypt,” she says.

“I came to study in the UK, trained at the Architectural Association, went back to Pakistan having graduated, and found I was drawn to the old buildings there that were in a state of neglect.”

The pull of historic structures eventually led her back to Britain. “I did some research at Oxford into the buildings, then went back and did conservation in Pakistan. I returned to the UK to do more research, ended up working in a conservation firm, and I’ve never looked back.”

Proud practice heritage

Donald Insall Associates has built an enviable heritage of its own. The 65-year-old firm, 95 per cent owned by an employee trust and a certified B Corp, remains proud of the role that its founder played in shaping best practice in conservation.

This year marks 50 years since the first European architectural heritage year, a moment that helped to transform attitudes towards historic buildings and paved the way for initiatives such as Open House. Proudfoot points to the firm’s role in that shift.

“That whole thing started with the work Donald did in Chester, which paved the way for the conservation management plans that are now the blueprints for how we go about understanding historic buildings and places, and how you knit together all the disparate pieces of a city,” he says, gesturing to a battered copy of Chester: A Study in Conservation lying on the desk.

“The whole business of controlling traffic, pedestrianising streets … All of that comes out of the Chester report. So Insall is embedded in the story of how we make heritage environments liveable and relevant.”

Hasan adds: “At that point they saw old buildings as a burden, and they were knocking them down. It was Donald who explained they are actually an asset if you think innovatively about how to reuse them, and bring together the local authority, local people, business owners, and give them a direction.”

While much of the sector focused narrowly on preservation, Insall’s approach was different. “He was doing that when everyone else who dealt with old buildings was old and stuffy, and all they wanted to do was preserve them,” Hasan notes. “But he talked about conservation and managing change. And it’s that mission we are continuing and reinvigorating today.”

A future vision rooted in Sir Donald Insall’s philosophy

Insall himself, now 99, was the inaugural recipient of Building Design’s lifetime achievement award in 2024 and remains a consultant to the business. “He was coming into the office regularly until Covid. In fact, he was in here a fortnight ago,” Hasan smiles.

Looking ahead, Proudfoot explains that the practice is focused on refining its identity while staying true to its founder’s values. “We have got a young leadership team in place now. We are working with brand consultants to refine our identity and, in doing that, we find ourselves turning so much to Donald’s original philosophies.

“What he stood for back then is not broken. It is absolutely still relevant now.”

Proudfoot notes that the firm is now more diverse than it has ever been, describing this as a great source of strength. Hasan draws parallels between her international background and the layered histories of the buildings the practice cares for.

“I am part of a global culture in which you are born somewhere, you grow up somewhere else, and you study somewhere else. I am at home in all three, feel they are all mine, and that I belong in all of them. I think the buildings we look at are a bit like that, too.

“That is what is wonderful about heritage: it is just layers of people coming and building and expressing and changing. That is what fascinates me. It is not just the physical fabric of it, but the memories. That is what makes them most nostalgic.”

When it comes to the climate crisis and the wider push for sustainability, Hasan highlights the particular position that conservation occupies. On one hand, she says, the field has always embodied sustainable principles through repair and reuse.

Robin Dhar, the firm’s chairman, on conservation’s wider purpose

As chairman Robin Dhar has noted elsewhere, the value of historic buildings lies not simply in their age but in their quality. “It’s not about being old or modern. It’s about good design – about proportion, qualities of light, sound, and how you feel in a space.”

Conservation, he suggests, is fundamentally about ensuring longevity. “Our challenge is to design alterations that enable a building to have a good life moving forward, without losing what makes it special.”

Reflecting on the evolution of the practice, Dhar has also remarked that Sir Donald Insall’s original ethos was quietly radical. “In 1958, Donald was swimming against the tide. Far from being traditionalist, he was being rebellious.”

Today, Dhar sees clear parallels between conservation and sustainability. “The objectives are the same: long life, durability, renewal. That is why the current focus on retrofit and re-use feels like a natural extension of the work we have always done.”

“It is all about maintenance. The reason we still have ancient buildings is that they have been repaired over time and nobody minded having a patch added to their windows or a panel used from one room to another. That is how we need to look at materials today.”

Hasan continues: “We are promoting a way of building structures that is less reliant on new materials. For example, we use big pieces of stone set in lime. You can take them apart and reuse them. Today they put on a 10 or 15mm fascia of lime which, once you have put it in, it is gone.”

On the other hand, best practice around insulation and airtightness often seems at odds with the fabric of traditional buildings. Proudfoot points out that “SPAB (the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings) has done a lot of work on the insulation of old buildings, and it turns out brick walls actually perform a lot better thermally than people thought, which means adding layers and layers of insulation on top, and taking away all the cornices and skirtings, might actually not be the right thing to do.”

He reflects: “We have been quietly managing change in historic buildings for more than 60 years. Now, with the rise of retrofit and sustainability, there are labels for it, and people are attaching themselves to those. But we have been doing those things for decades before they were fashionable. It is built into the way we work.”

Wentworth Woodhouse

The question of whether to rebuild or reinvent historic structures remains a live debate within heritage architecture, as the controversy over Allies and Morrison’s proposals for the National Trust’s fire-damaged Clandon Park illustrates. Insall deals with such questions daily. Proudfoot declines to comment on Clandon Park, instead highlighting his firm’s work on the Camellia House at Wentworth Woodhouse.

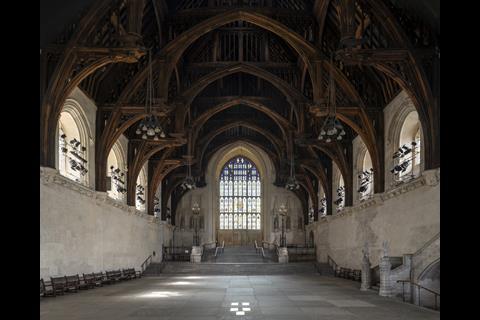

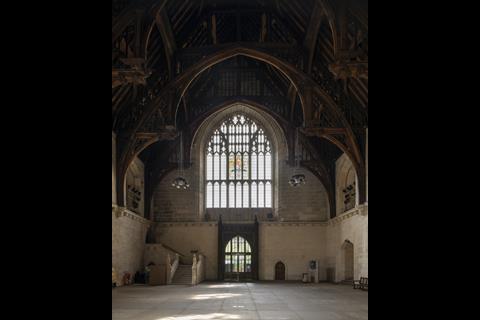

Located near Rotherham, Wentworth Woodhouse is one of the country’s largest stately homes but had fallen into serious disrepair. The Insall team has been involved for almost a decade, advising the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust and overseeing the long-term restoration. Such extended relationships are typical for the firm, which recently spent a similar length of time working on Westminster Hall.

The first priority was repairing the 3,250sq m roof to prevent further damage to the 17th and 18th-century fabric. With that secured, focus shifted to repurposing parts of the estate to generate income. The Camellia House, a Georgian glasshouse that had stood roofless and neglected for more than fifty years, reopened last year following an Insall-led refurbishment.

It now houses rare camellias, a restaurant and events space. Innovations included an air-source heat pump and underfloor heating. “The building originally had underfloor heating in the shape of a hypocaust, so the new underfloor heating seems entirely appropriate,” says Proudfoot.

The project represents a modern approach to conservation, incorporating features such as rainwater harvesting and a Changing Places toilet. “Our clients have changed over the years,” Proudfoot adds. “It is not just the aristocracy we work for nowadays, it is a much wider clientele. “The Wentworth Trust are a good example of this. They want it to be the most accessible and sustainable stately home in the country.”

The next phase of work will focus on restoring the stables.

Blencowe – a ruin revived

Another potentially controversial project that Insall successfully navigated to completion is Blencowe Hall in Cumbria. Here, a new building was inserted into the shell of a pele tower blown apart during the Civil War. With its dramatic V-shaped split down the facade, the tower had stood roofless and empty for centuries before its revival as a modern hotel and hospitality business.

Securing listed building consent proved the greatest challenge. The proposals included reglazing parts of the tower and inserting a new structure within the historic shell, both potentially contentious.

Reflecting on the process, Proudfoot says: “What helped us gain the consent was the fact we had done thorough archaeological work to understand the site, including with ground-penetrating radar – that and the fact we could make a good, strong, confident case for the scheme.”

From Westminster Hall to town halls

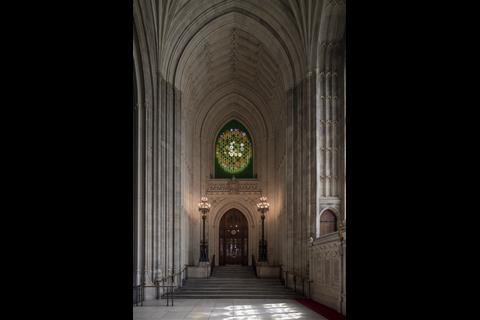

The full range of services offered by Donald Insall Associates includes conservation architecture, heritage consultancy, new design in heritage settings and townscape advice. The practice is regarded as a safe pair of hands by custodians of the country’s most important historic buildings, including many National Trust properties and royal palaces.

New conservation techniques are continually developed and applied. At Westminster Hall, for example, nanolime was used to consolidate weathered limestone, and latex poultices to remove staining.

Proudfoot emphasises that the practice’s projects require both strategic thinking and detailed conservation expertise. “We have got the capacity to see the big picture and understand the end goal, as well as having lots of people who can really zoom in on the detail and be really pernickety about the cornice,” he says.

Hasan expands: “You need to understand how to get the building to the next stage, how to alter it, how to change it, how to make it more relevant to a contemporary way of living. That is what keeps buildings running. Donald calls it ‘living buildings’.”

Insall’s recent work on Rochdale’s 1871 Crossland town hall illustrates this approach. The project was not just a restoration but had a strong social dimension, particularly important in a very economically deprived area. Hundreds of local volunteers contributed, and a heritage skills workshop was set up in the basement to train local people.

Church crisis

Another significant but less high-profile area of the firm’s work is church conservation, where some buildings are being modernised with technologies such as ground-source heat pumps and infrared heating. “We are probably responsible for 400 or so churches, and we have a good number of church architects within our team,” says Proudfoot.

“To be honest, we subsidise that work because the amount the Church of England gives you for a quinquennial inspection does not really cover the cost of the work involved.”

Hasan reflects on the wider challenge facing the sector. “Forty years ago, the country house was the crisis. Now churches are the crisis. We have so many, and we do not know what to do with them.

“They are all grade I listed and the congregations are dropping like flies. They are going to have to be repurposed. That is a massive issue. It is another conversation within our team.”

Twentieth-century buildings

At the other end of the conservation scale, Insall is increasingly being consulted on modern buildings. The practice recently acted as consultants for Squire and Partners’ refurbishment of Space House, the grade II-listed 1960s modernist landmark on Kingsway in central London, designed by George Marsh of Richard Seifert and Partners.

“We were discussing that in the leadership team the other day,” says Proudfoot. “Making sure we have the right knowledge base to deal with all the enquiries about concrete.”

Hasan highlights one of the specific challenges. “Those buildings can be more difficult to conserve because the reinforcement rusts. It is not like a piece of timber floor, which you can add to or change. Concrete floors are quite difficult,” she says.

Despite the different materials, Proudfoot believes the conservation approach remains the same. “You apply the process to understand what the material is composed of, how it is behaving, and then you take it step by step. Whether you are cleaning a marble statue or conserving concrete, you do samples and trials.

“That is where you start. You have got to understand the material, and the value and significance of the building, before making the right next step.”

Hasan is currently involved in a post-conflict reconstruction project at the Mosul Cultural Museum in Iraq, a modernist concrete building from the 1970s designed by Mohamed Makiya. The building was badly damaged in 2014 when Daesh (ISIS) attacked the site, destroying sculptures and burning the library, causing the concrete floors to bow under intense heat.

“It is an international team working on it and it is a wonderful thing,” she says. “For me it is quite cathartic. I love that part of the world. But it is in the red zone, so I cannot ask anyone to go with me.”

Navigating risks old and new

Back in the UK, another challenge the firm faces is navigating one-size-fits-all insurance requirements. “Our new battles are with insurers, and with people who depend on warranties and need stock answers for stock questions,” says Hasan.

Defending conservation principles against rigid expectations, she explains, often means standing firm. “No, actually, it is fine if that casement has a little bit of scarfing on it. And no, I cannot give you a piece of paper saying it will last 20 years, but I can tell you this window has been there since the 16th century.”

She also highlights the uneven tax treatment that historic buildings face compared with new construction. “We have the 20% VAT that does not exist for new build, but does for old buildings. So, the world disenfranchises them, and yet they exist.”

Looking to the future, Proudfoot reflects on some wider questions facing the sector. “There are always new questions to answer, like how do you make grade I listed country houses appealing to a diverse younger generation? These are the things that interest us.”

Alongside the depth of heritage expertise for which Insall is known – “No one ever leaves, you know,” Hasan smiles, “we have people in their 70s and 80s still sharing their knowledge” – a new generation of leaders is now focused on contemporary challenges.

“This new phase has echoes of where Donald was in 1957,” she says. “There was an urgency then, a crisis for our historic buildings. And here we are again, in a new crisis, and Insall is here dealing with it again.”

Are we all conservation architects now?

Conservation today is less about resisting change and more about managing it with care, imagination and a sense of responsibility. With its long history of innovation in the field, Donald Insall Associates shows how a respect for material authenticity can sit alongside a willingness to address contemporary realities, whether that means advancing sustainability, responding to social need, or finding new futures for historic structures.

The future of architecture itself may increasingly depend on this mindset. Former head of the London School of Architecture Neal Shasore recently observed to BD that “we are all conservation architects now”. His comment captures a wider truth: re-use, conservation and retrofit are no longer specialist concerns but central to how the profession must respond to the climate crisis and the evolving needs of society.

With its accumulated expertise and renewed energy under new leadership, Donald Insall Architects appears well placed to help define how heritage and sustainability can be successfully intertwined in the decades to come.

>> Also read: Orms: designing architecture that listens and responds to a changing world

>> Also read: Research, empathy and quiet radicalism: the key ingredients in ‘Saunt sauce’

Postscript

No comments yet