From backland sites to dark kitchens, Dowen Farmer Architects relish unusual and challenging projects, finds Ben Flatman

Dowen Farmer’s office sits on the upper floors of Peckham Levels, the former multi-storey carpark turned creative hub and events space. Reaching their office involves navigating the split-levels and old vehicle access ramps that form the core of the building’s circulation.

On my way up to meet the practice’s founders, James Dowen and Tom Farmer, I find myself doubling back to explore further. I finally reach my destination after taking a circuitous route via independent coffee shops and a range of interesting-looking design consultancies.

If Peckham Levels offers multiple unusual routes by which to reach your destination, it feels appropriate that this is where Dowen Farmer have chosen to base themselves since 2018. Both Dowen and Farmer have pursued unconventional paths through practice, working for big names as well as unknowns, and pursuing their passions, whether they be boat building and craft, or office dogs and offbeat commissions.

The practice was established in 2017 and has been building a reputation for innovative housing schemes on challenging sites. It also has a growing reputation for working with complex and challenging design briefs.

Current projects include maintenance depots for National Highways and two high-rise “dark kitchen” schemes (a fast-expanding typology from which takeaway or catered food is prepared). All of this sits alongside the more conventional commercial and residential work that you would expect to find in a rapidly growing young practice.

Although they didn’t know each other and were in different years, Dowen and Farmer both started their studies at Newcastle. “The design ethos at Newcastle was very community focused,” says Dowen. “It really influenced the way we work”. Dowen ended up staying for his Part 2, while Farmer opted for the Bartlett.

Farmer grew up in a military family. With a father in the army, he moved around a lot. This peripatetic lifestyle rubbed off and, after school, he spent a lot of time travelling while also applying his passion for making things to boat building and surfboards.

At the Bartlett, Farmer joined Bob Sheil’s workshop-based Unit 23. “I had always seen making and architecture as separate,” he says. The Bartlett enabled him to merge these two passions. After graduating he took a job at Benoy, where he met Dowen and they struck up a friendship.

They both see Benoy as an excellent training ground. “The design directors at Benoy were relaxed about letting you get on and design,” says Dowen. “They were good at letting younger members develop and take on more responsibility.”

“It was a lightbulb moment,” he says. “I needed to step outside of the large-scale environment.”

Dowen was able to work on a range of large projects at Benoy – including schemes in India and the Middle East, often for the real estate arm of the Indian conglomerate Tata.

After a year, Farmer moved on. His passion for making meant that he “gravitated to Heatherwick”, where he worked as a designer/maker. “There was lots of prototyping,” he says. Involved in a lot of Heatherwick’s New York projects, he describes it as an “amazing environment to work in. Rich with ideas.”

During this time Dowen and his wife (also an architect) were renovating their own house. The experience gave him a taste for working on smaller-scale projects and he decided to also make the move away from Benoy. “It was a lightbulb moment,” he says. “I needed to step outside of the large-scale environment.”

Dowen joined a practice, Shard Architects, working on high-end west London residential projects and says he “ended up almost running the studio”. It was, he says, “great experience of running a practice”.

A formative experience was running a complex conversion of a grade II-listed church that had already been on site for four or five years when he took it on. While project managers came and went, the architects remained on the project throughout and Dowen retains a good relationship with the client.

“It was going way beyond the role of the architect as I’d understood it up until that point”

He describes how he was “practically living on site” and learning how to get a struggling project mobilised. “It was going way beyond the role of the architect as I’d understood it up until that point,” he says.

The experience gave him invaluable exposure to the mindset of contractors and also an insight into the challenges that they face. “It made me wonder if every architect should spend six months on site. I really feel like it gave me an understanding of everyone around the table on a project”.

It was around this time that the thought of setting up a practice together began to solidify for the two of them. “Friends and clients kept on asking if we’d do some work,” says Farmer. Dowen took the leap first and was soon “drowning in work, but not fees”.

They were invited to design a building for a small vineyard in Yorkshire and got the scheme approved through permitted development. Although the client proceeded to the construction strage without an architect, the experience gave them the confidence that they could make a go of the practice.

Speaking about the decision to leave Heatherwick, Farmer says: “It’s a terrifying moment when you’re going to hand in your notice and are contemplating all the risks. It’s such a big moment to give up good jobs working on big projects. But I was still quite young and didn’t have the added pressure of kids and mortgages.”

For Farmer the real challenge after finally setting up on their own, was making that step back into larger multi-unit residential work

Perhaps surprisingly, neither Dowen nor Farmer took any clients with them when they left their jobs. “We started from nothing,” says Farmer, “doing side returns and loft conversions.”

Farmer also brought in a yacht refurbishment. “Basically a full rebuild of a 50m boat,” he says. “It made me feel more comfortable about moving on.”

Dowen reflects on their experiences at Benoy and Heatherwick. “Our bread and butter had been public-facing big projects,” he says. “We’d always worked on such a range and variety of interesting projects – they were the kinds of briefs you’d get at university.” The change of scale after setting up on their own was significant.

For Farmer the real challenge after starting their own practice was making that step back into larger multi-unit residential work. “How do you convince clients to go with you on a larger scheme when you’ve only got small resi experience under your own name?”

But, after earning their stripes with smaller projects, the practice is now building a growing reputation for multi-unit residential work. Farmer says it’s “only now that we’re getting back into our comfort zone – the place where we can do our best work”.

It may seem like a roundabout way to build a practice, given their backgrounds and extensive experience on large projects, but the organic growth and feeling of having built something from scratch clearly fills them both with a sense of satisfaction. “We’ve worked through small-scale schemes to start doing more public facing projects,” Farmer says.

“This is the scale at which we can deliver to the best of our ability. We did it backwards – big first and then going back to small stuff.”

Growth in the team and an increasing industry profile are bringing new challenges, as the pair seek to turn critical success and a burgeoning workload into profitability. They both know that they are navigating a tough industry and market and are concerned and stimulated by the challenges the industry presents.

“We see other studios putting in very low fees to make the leap to multi-unit resi schemes,” says Dowen. “It’s a real problem with the industry,” he adds.

“If you’re not doing it, then you’re not going to get the work. How can we get that value back? We’ve let ourselves down as a profession.”

Farmer admits that they have learnt some tough lessons on the job

But they both know that the pressure to charge low fees and offer freebies is hard to resist. “We made a commercial decision to help unlock a site for the client. Will did a full pre app/feasibility study at no cost. As a growing studio with ever increasing overheads, it becomes much harder to offer that level of freebies,” says Farmer.

“Clients expect fees to be a lot lower when up against larger, more experienced practices, even though our staffing level and service is often better.” says Dowen. “It’s hard to commercialise the value we add,” he notes, echoing a problem faced by so many in the industry. “It’s [working for free] that wins you the project, but you don’t want to just give it away.”

Farmer admits that they have learnt some tough lessons on the job. “We had our hands burnt with clients taking our work and using another architect for implementation.” he says.

“It’s a real learning process. Where is the line between trying to win a project and giving ideas away for free?” He looks at how things worked at Heatherwick and wonders whether it should not be an industry norm: “At Heatherwick, clients have to sign a contract before pen hits paper.”

Talking about how the practice has evolved its approach, Dowen adds: “But we understand the risks of development and a huge chunk of it falls with the developer. We understand the need for fast and loose site appraisals to gauge if things could stack up, and we have learnt to quickly test sites at a high level to try and help developers assess sites at speed, without killing the commercials within the studio itself.”

The work is eclectic and interesting

Now the practice has a few built projects under its belt and is looking for larger, more complex work. “It’s rewarding to see actual buildings going up and our Part 2s on site getting the experience,” says Dowen. The practice has already built around 12 projects, including two or three multi-unit schemes. “Within a year we should have another five or six built schemes,” says Farmer.

The maintenance depot job for National Highways at Milton Common has tapped into the practice’s knack for getting the most out of difficult sites – in this case, the awkward leftover plots you whizz past around motorway interchanges. But the practice does not see it as simply a fee earner from which they will move on to more glamorous commissions. There is a genuine interest in the project - a reflection of both Dowen and Farmer’s desire to bring design integrity to every commission.

The work is eclectic and interesting. “We haven’t specialised in terms of typologies”, says Dowen. But one of the practice’s area of expertise is small or complex back land planning approvals, where they are able to unlock challenging sites and add density. “This brings in more clients,” says Dowen.

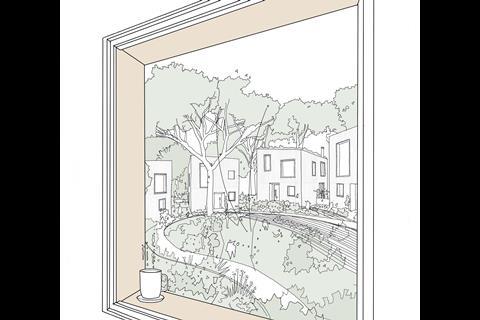

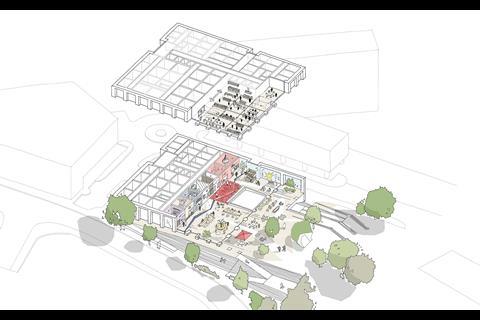

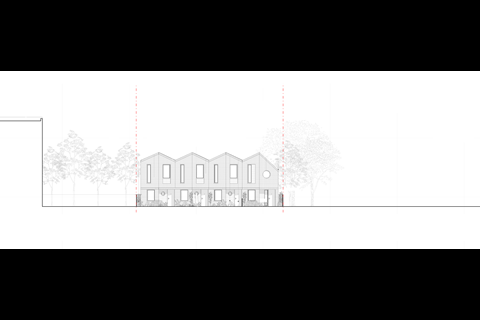

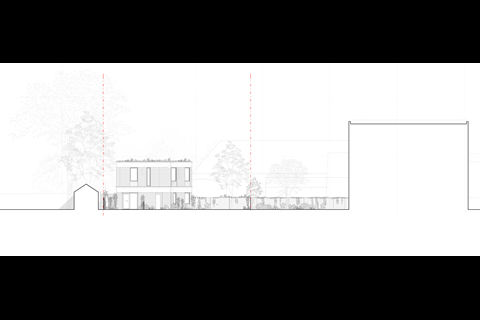

Wilmer Place was a key project for the practice. Comprising 28 units on a challenging backland site, it helped demonstrate to developers that the practice could add real value. “Unlocking value in difficult sites, such as Wilmer Place, helped us get into larger multi-unit projects,” says Farmer. “Wilmer Place was a lifeline at the start of covid” says Dowen, “and then it just snowballed. We grew from four to eight staff. We have Jon Ellis from Artform to thank for that initial leap of faith in us.”

The practice is happy to work on some unusual typologies that are pushing the boundaries of architectural work. They are currently developing two schemes for what have become known as “dark kitchens” – locations, usually in inner urban areas, where kitchens churn out cooked food for delivery. Dowen describes these projects, both for Dephna Group, as “super exciting”. One of the buildings, which forms part of the north Acton masterplan, is 16 storeys high. “It’s industrial in the heart of London,” says Dowen.

“If it goes ahead it will deliver 15% of the borough’s new employment target,” says Dowen. “It’s a delivery hub with a ground-floor market place which the council are keen to encourage because of the variety it adds to the masterplan.”

Farmer adds: “I’m most excited by the projects where other architects are not interested.”

Discussing office culture, Farmer highlights the way in which they constantly reallocate resources as required. “We discuss weekly what support people need and the team move around projects to help out where needed. It keeps people engaged.”

When it comes to remuneration, Farmer says the company profit-shares on an ad hoc basis: “If a project delivers, then there is a financial reward for the team.”

Their location in Peckham is also important to them. “We feel engaged with Peckham and we’re rooted here as a practice,” says Farmer, before pointing out the window to the nearby Aylesham Centre where they are working on a project.

Cultivating a relaxed and productive office environment is key to their ethos. “People come here with ambition and we try to provide them with an opportunity to get stuck in and add their design stamp to each and every project” says Farmer.

“There is no in-house design style that is fed down from the top; we actively encourage each team member to bring different design positions to each project, which makes the end product more engaging and usually site specific.”

The office accommodates up to 12 staff, which is stretching their current space to its limits. But there is some flexibility on home working for those who want it.

“We offer work from home on Wednesdays, which breaks up the week nicely, but fundamentally – as a creative outfit that thrives on engaging as a team – we feel that being together for the rest of the week enriches both the design process and the end product,” says Farmer.

Dowen agrees: “We try to operate like a university studio – genuinely collaborating throughout the day.”

Looking to the future he adds: “As we grow, trying to avoid falling into the trap of becoming more corporate is important. We try to remember that the reason why we set the studio up in the first place was to try and foster a very collaborative, energised environment to throw ideas around.”

No comments yet