Patrick Lynch and Kieran Long discuss Sigurd Lewerentz, Swedish architectural culture and museums as ‘machines for depolarisation’

Patrick Lynch: The first time I remember discussing Lewerentz with you was at one of Peter Carl’s MPhil/ PhD seminars at London Met, in late autumn 2011, or early 2012, I think. I went on to write a chapter of my doctoral dissertation on him, which was subsequently published in Civic Ground (2017); you’ve curated the exhibition at ArkDes and made the beautiful catalogue accompanying this.

The initial conversation in which Lewerentz cropped up began with Peter observing that very few famous churches by modernist architects, in contrast to almost everything produced in the C19th, actually work as Parish churches. Ronchamp is a pilgrimage chapel without a regular congregation, La Tourette part of a Dominican monastery, Rothko’s chapel in Houston part of a university campus, ditto Sarrinen at MIT, etc.

I mentioned St Peter’s, which I’d visited with students, as just a regular parish church, something that is just part of a parish and town. It’s obviously a lot more interesting than most parish churches - largely to do with the intensely creative relationship between the architect and the diocesan client representative Lars Ridderstedt, who went on to complete a PhD as a retired priest, detailing his working relationships with Lewerentz and Peter Celsing.

Nonetheless, it’s success lies in being part of the ritualistic and everyday life of Klippan, and I can’t help seeing the fruits of that conversation in your attitude towards the exhibition, the title of which emphasises that Lewerentz wasn’t just the architect of projects concerned with death, as he has hitherto been principally known, but an architect whose work and ethos embraced a vast range of projects you’ve revealed: including many commercial office and retail projects, as well as some joyous festival settings and landscapes.

He also ran an ironmongery business and was a devout Lutheran. You’ve brought to light the life aspect of his work. Do you think that the research is in some ways perhaps a little controversial - I mean in the context of the dominant narrative of modern Swedish architectural history, which emphasises collectivity and the role that C20th design played in shaping a social identity?

Kieran Long: One of the more straightforward aims with the Lewerentz project at ArkDes was to give a more balanced view of his long life and career. If you know anything about Lewerentz, you are most likely to associate him with the churches (St Mark’s in Stockholm, St Peter’s in Klippan) or with his two monumental cemetery projects (Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm and the Eastern Cemetery Malmö) which occupied him for more or less his entire career.

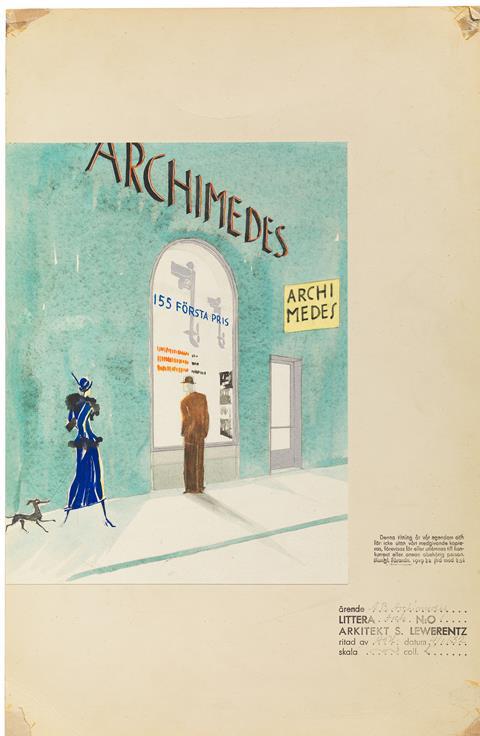

My colleague Johan Örn’s archival research put special emphasis on the 1920s and 1930s, when Lewerentz was a busy commercial architect in the growing modern metropolis of Stockholm. We see in the book and the exhibition how he was intensely busy, and engaged with design tasks of every kind, from furniture, industrial design and graphic design as well as making architecture for more or less every modern typology: offices, shops, housing, hotels and department stores, competitions for museums and even for Sweden’s first airport.

In that period his architecture has a very different visual character to the churches, but I think you can see that the drawings demonstrate an empathy with the mundanity of the modern citizen. This, to me, is what makes Lewerentz important. I have tried to summarise that with our title. He is a rare architect who is interested both in very ordinary urban experiences (we see this especially in the amazing, filmic perspective drawings of his shops), but also in the profundity we are all capable of at important ritual moments of death, burial, baptism and so on.

The values that modern architecture adhered to in the middle of the 20th century, especially in Sweden, were connected with a social democratic political ideology that had as its goal an egalitarian society.

I have joked that Lewerentz seems interested in humanity at its most shallow and at its most deep, but not very much in between. If there is something controversial in our reading of Lewerentz it is, perhaps, this. The values that modern architecture adhered to in the middle of the 20th century, especially in Sweden, were connected with a social democratic political ideology that had as its goal an egalitarian society. The tools to achieve that were mainly technocratic – and politicians and many architects alike believed that through research and engineering, social justice could be achieved.

Most Swedish architecture in this period is a kind of manifestation of the optimism of this new social order. Lewerentz seemed to understand, though, that there were things missing from this way of building a city. In the social democratic world view, sprituality is dismissed as superstition and shopping is dismissed as consumerism: both are considered a kind of moral error. Lewerentz did not think this way and his work digs deep into both.

I think it is less that our reading of Lewrentz is controversial, but that it reveals Lewerentz’s work as a project of resistance against dominant modes of production in architecture in the 20th century. To be in resistance in that way is to put him in a category with other Swedish artists who do not fit the mould: Ingmar Bergman and August Strindberg spring to mind, both of whom had a tense relationship with their homeland’s cultural mores, but produced extraordinary modern art anyway.

PL: It seems to be that architectural discourse and, in particular the history of modern architecture and design as written by art historians, is stridently Middle Brow?! The elision of social virtue with white architecture - an unwitting continuation of the “Englightenment” project of what Rykwert calls The First Moderns - leads to a sort of rapturous smugness, coexisting simultaneously with nostalgia for a lost modernism, in a lot of uncritical people.

My sense is that exactly the same people who have been making a living peddling the myth that they knew Sigurd briefly as an old man, have been shocked to learn that he was a capitalist, a Christian and someone whose best work is less a product of individual genius, as the fruitful collaboration of a host of artists and poets and priests and parish groups.

Lewerentz doesn’t fit the nicely curated image of Scandinavian liberalism

A Stockholm architect told me last week that SL was ostracised from Swedish architectural culture by jealous and envious peers, and that this explains in part the reluctance of the older generation to celebrate him, i.e. it is guilt in part, and also a certain resistance to disrupt the cosy national self-image that design historians have so carefully manicured.

The Sallander novels reveal how this tendency towards nationalistic complacency only partly manages to camouflage the actual complexity and brutality of Swedish society. Or rather, of any human culture, where agon and strife are typical, born as we are, as Joyce observed, between piss and shit. Lewerentz doesn’t fit the nicely curated image of Scandinavian liberalism: he was too earthy and too cosmic I think, which the exhibition beautifully reveals.

Can you tell us a bit about the SL exhibition in terms of the layout by Caruso St John; the films that you commissioned/found and the music. And also can you please say something about the other recent projects you’ve done (with James Foster-Taylor) at the museum please? You’re about to embark on a major overview of Swedish architecture based upon the ArkDes archives. Do you think you have an obligation to try to tell a social history of a nation via its material culture and spatial ambitions? And after this, what’s next?

KL: The exhibition was a long project, and that gave us the chance to add a series of things that I think make it more immersive and more emotionally engaging than many architecture exhibitions. The exhibition design by Caruso St John was brilliantly done. Adam Caruso has a longstanding interest in and passion for Lewerentz’s work, and he had the confidence to use colour and to create proportions and atmospheres in the rooms in a way that I think few other architects would have.

Nina Lundvall, who worked on the project with Adam, is Swedish and such an experienced and skillful architect. The design becomes experience in itself. The precisely selected silver foil finish in the room about the Black Box (Lewerentz’s last working room in the 1970s, with its distinctive silver interior) or the exuberant wallpaper in the room about Lewerentz’s 1920s and 1930s add a lot to the momentum and atmosphere of the show.

We commissioned a number of film works, some using archival footage and put together by the filmmaker Sven Blume, who we are now helping to make a full length documentary about Lewerentz for Swedish television. We also commissioned Karin Ekberg to make two new films about the cemeteries that help bring the scale of the landscapes into the room. Add to that the brilliant new photography of the projects by Johan Dehlin, also commissioned by us for the book and exhibition, and there is actually a huge amount of ‘contemporary’ visual material that provides ways into the story and the work.

I am totally convinced that architectural drawings can be just as compelling in a museum or exhibition as any modern artwork

I was determined that this show should have a quality that if you were a member of the public in Sweden and were only ever going to see one exhibition about an architect ever, this should be it. It has tremendous depth of research, but there is also a huge amount of care for the visitor, too. I am totally convinced that architectural drawings can be just as compelling in a museum or exhibition as any modern artwork. The trick is to take them as seriously as great art museums take artworks. That involves interpretation and selection, but also a commitment to conservation, mounting, design and lighting that is expensive, but that I think our show proves can work.

Other projects at the museum do not look very much like the Lewerentz project! ArkDes has a diverse remit, both as a national museum and as a policy think tank in the context of the Sweden’s national policy on architecture and design. Our output is quite diverse, and we try to maintain a faster, more flexible line of exhibitions running alongside the large-scale projects. One important field of activity for us is trying to understand what fields of creativity are emerging from the digital realm that can help us understand new aesthetic expressions of our commonalities.

Weird Sensation Feels Good, curated by my colleague James Taylor Foster, is a great example. It is an exhibition about ASMR, the internet phenomenon that uses film to affect the viewer’s body and senses, through use of strange sounds and images. It seems to me that ASMR is vital for us to pay attention to as a design culture. Anything that takes seriously the effect of aesthetics on the body is something that can enrich our understanding of architecture and design. The exhibition recently opened at the Design Museum in London on tour.

Cities begin in the mind

And as for what’s next, my most ambitious project is to create a completely new experience at ArkDes’ home in Stockholm in time for 2024. The museum has suffered for a rather long time from not using its historic buildings very well and we will address that. But at its heart our ambition for 2024 is to display works from the entire collection in a new historical narrative of modern Swedish architecture and design. This has never been done before in Sweden, and gives us the chance to bring out never-before-seen works from architects like Ragnar Östberg, Cyrillus Johansson, KF, Eric and Tore Ahlsen, Backström & Reinius, Sven Markelius, Leonie Geisendorf, Ralph Erskine, Klas Anshelm and many more.

The process, which has already been underway for some years, is also allowing us to experiment with new, object-based methods of interpretation, research and visitor experience. Cities begin in the mind, as David Graeber and David Wengrow recently reminded us, and the 4 million drawings in ArkDes’ collection are an extraordinary document of one culture’s attempts to imagine collective life. I think people will love it.

PL: That’s very interesting Kieran, thank you. One last thing, I’d like, if I could, to ask you about writing, and about the relationship between this and curation. You started off as a graduate employee at BD and then worked at the inception of Icon, writing a lot, and travelling to see new buildings. Do you think this helped your development as a thinker about architecture and architectural exhibitions? And to conclude, what are you writing now, or plan to write next?

KL: Writing is thinking, really, and what I have found wonderful about joining the museum world is that there is quite a bit of space for that. When I started at BD, there were a load of smart, fast, talented people there: the late Marcus Fairs, Rob Bevan, Gareth Gardner etc. That was an amazing proving ground, a weekly magazine with a competitive news cycle. But museums force you to take your thinking more seriously and to take it a lot slower. When I joined the V&A I was basically told that my job was to be the country’s expert in architecture and design.

What one chooses to do with that vague, intimidating mission is really up to you, which can lead some to disappear into their rooms and write obscure books. For me, the exhibition medium is definitely a great storytelling medium, one that can reach out and grab audiences emotionally and sensorially. Architecture, or at least the architects I grew up learning from and writing about, taught me to ‘read’ with all the senses, with the body as well as the mind. Exhibitions combine this experience with a need to create a place for a kind of freedom of thought.

I believe, perhaps naively, that museums can be machines for depolarisation

Next will come a comprehensive exhibition of the whole collection at ArkDes – a semi-permanent display of the whole history of modern Swedish architecture. This is a story that has never been told, and a collection that has never really been displayed. Sweden is a small country with an extraordinary number of talented architects (Ragnar Östberg, Carl Malmsten, Cyrillus Johansson, Lewerent, Gunnar Asplund, Ivar Tengbom, Sven Markelius, Backström Reinius, Leonie Geisendorf, Ralph Erskine, Klas Anselm etc) in the national romantic, neo classical and modern periods.

It will be exciting just to show this stuff, and weaving a big picture story about that is a fun task. We have just had an election here that shows that Sweden is just as divided as most other western countries. I believe, perhaps naively, that museums can be machines for depolarisation – a great exhibition makes a space of freedom for new thoughts and new aesthetic experiences. That is a kind of freedom we all need right now.

Postscript

Patrick Lynch is director of Lynch Architects and publishing editor of Canalside Press

Kieran Long is director of ArkDes, The Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design

No comments yet