Architects must reclaim their ethical self-determination amidst the ideological mandates of modern professional practice, writes Helen MacNeil

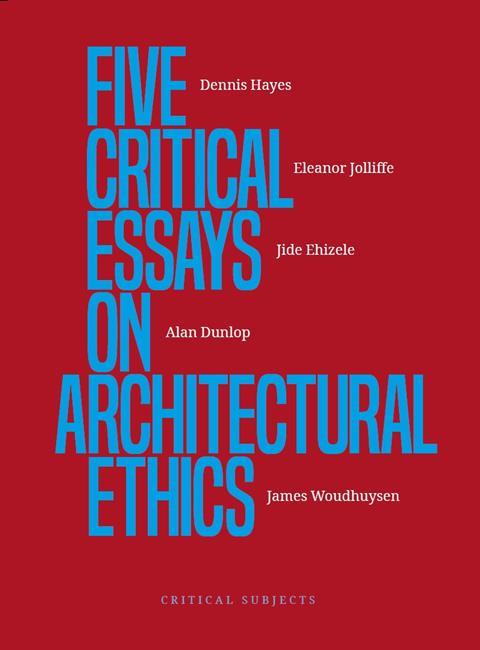

Five Critical Essays, edited by Austin Williams, is a collection that seeks to reinvigorate critical thinking, common sense and objective ethical discourse. It stands as a noble endeavour in authoritarian times.

The series of pamphlets argues that, as a profession, we have observed the externalisation of our individual moral compasses to a collective morality bureaucratised through DEI initiatives, ESG criteria, and Net Zero mandates dictated by those who manipulate societal fears into moral imperatives.

If we are unable to frame political and ethical issues honestly or objectively, then we are compelled to comply with dogmas and ideologies that only offer prescriptive and overly simplistic solutions to complex problems. This approach stifles innovative solutions that could emerge from genuinely diverse ethical debate. In the conclusion to the series of essays, Patrik Schumacher convincingly argues for a return to ethical self-determination rather than a collective conscience where, as Dennis Hayes proffers, we are told, “do X because it is ‘sustainable’, ‘inclusive’, ‘diverse’ etc”.

Five Critical Essays on Architectural Ethics urges readers to reassess contemporary ethical norms and resist ideological encirclement. Each essay presents fresh insights, emphasising the importance of contestability in ethical positions, akin to the rigour demanded in scientific inquiry, and the rejection of moral coercion or “moral bullying” as Adam Dunlop posits. Where conformity trumps competence, for career progression, these essays serve as a vital wake-up call.

The collection highlights the transformation of architects into activists, whether they want to or not, bound to ideological agendas rather than committed to the pursuit of truth and knowledge. The writings challenge the prevailing status quo, urging architects to reclaim their agency and engage in genuine ethical inquiry instead of blindly adhering to fashionable dogmatic frameworks. As Dennis Hayes eloquently states, “When conformity is demanded of a student or professional or if any viewpoint is forced upon our thinking, then this is unethical”.

Jide Ehizele refreshingly challenges the notion that inclusive growth is economically sustainable in developing countries and bemoans the fact that we are witnessing the rejection of “the universal idea of ‘economic growth = progress’”.

This collection of essays is a rallying cry, urging us to cast aside the limitations of narrow perspectives and wholeheartedly embrace the profound ethical challenges within our field

Alan Dunlop says that, as architects are no longer involved in the delivery of mass housing, our purpose as architects is “to make humble improvements in the built environment and ordinary people’s lives – rather than imagining that an architectural project can manipulate the global climate”.

James Woudhuysen argues effectively that the quest for Net Zero cannot be termed ethical if it slows the provision of much-needed housing, and that we are seeing a “a wilful refusal to accept that there are any ethical dilemmas associated with the opinions of the gatekeepers of climate change policy.”

I particularly enjoyed Dennis Hayes’s reference to philosopher and educationalist, Mary Warnock and the observation that our society has been infected with moral relativism, her warning that there are “so many worldviews in a plural society that it seems impossible to prefer one over another. In this way, moral judgements become nothing more than expressions of personal preferences.”

BD’s own Eleanor Jolliffe highlights that professional conduct traditionally involves qualities like honesty, integrity, and ethical behaviour. She criticises RIBA for codifying Social Justice and Environmentalism into the Code of Conduct that requires ‘action’ and states that the 900% increase in diktats “seem to signal a reduced level of trust in the architectural profession”. A coddling and infantilisation of the profession.

We face moral coercion, compelling us to accept falsehoods as truths, unethical behaviour as ethical, and moral actions as immoral. We are navigating an era of profound subversion. The remedy is the relentless pursuit of honest and open debate and the acquisition of knowledge through difficult arguments. The alternative is ever-increasing self-censorship, the holding of secrets and acceptance of mandated lies.

As Alexander Solzhenitsyn so aptly makes the case for ethical self-determination, “Even if all is covered by lies, even if all is under their rule, let us resist in the smallest way: Let their rule hold not through me! And this is the way to break out of the imaginary encirclement of our inertness”.

This collection of essays is a rallying cry, urging us to cast aside the limitations of narrow perspectives and wholeheartedly embrace the profound ethical challenges within our field.

>> Also read: Architects won’t save the planet

>> Also read: Review | RIBA Ethical Practice Guide

Postscript

Five Critical Essays on Architectural Ethics is edited by Austin Williams and published by TRG Publishing.

Helen MacNeil is founder of HA! Honest Architecture.

No comments yet