Ben Flatman speaks to Yasmeen Lari about her latest award, her career of three parts and what she plans to do next

For many, the award of the Royal Gold Medal is the crowning achievement of a long and illustrious career in architecture – an opportunity to look back and bask in some well-deserved recognition. But for the 2023 recipient, such self-congratulation seems a long way from her thoughts.

Yasmeen Lari, whose career has encompassed a diverse range of built environment sectors, seems temperamentally ill-suited to resting on her laurels. On the day I meet her at the RIBA’s Portland Place HQ, she is intent on finding a way to leverage the award to support her latest humanitarian project, as well as helping to ensure more architects can follow in her footsteps.

“I have to make use of it in some way,” she says of the Gold Medal. “How do I open up the field for others, for younger professionals?”

>> Also read: Yasmeen Lari is a visionary architect for our age. She deserves a Nobel Prize

In a recent article for BD, Susan Roaf described Lari as having had three distinct careers – first as a celebrated Pakistani proto-starchitect; then as a leading advocate for architectural heritage and conservation; and more recently as an activist, focused on zero carbon, sustainable livelihoods, and affordable housing. Roaf’s article left me wondering what had led Lari to pursue such a varied professional life.

Her father was an officer in the Indian civil service who had left behind his native Uttar Pradesh, for a posting in Punjab. She describes her early life as privileged and detached from many of the day-to-day realities of the world around her. “As a child I lived a very aloof kind of life,” she says.

I never really had the desire to be international. Your first thought was always for your country and how to help it flourish

When the rupture and violent upheaval of partition was unleashed by Britain’s abrupt departure from India in 1947, Lari and her immediate family found themselves already in Pakistan. “We were not really affected in any way, because we were already there [in Pakistan],” she says, before adding: “We didn’t go through the trauma that others did.”

I am surprised by her assertion that partition left little or no impact, and she concedes that what did make an impression were the conversations she overhead at home – stories of the horrific trainloads of the dead or injured arriving in Lahore’s central train station.

Her father was by then appointed as Pakistani deputy commissioner for Lahore. He also had significant responsibility for refugees and she remembers her mother being active in helping in the camps. It was “not unusual”, she says of her mother’s volunteer work. “That was your job.”

Her father was clearly a major influence. Prior to partition he had studied at Oxford for two years. He returned to the subcontinent full of an enthusiasm for modernity, including modernist urbanism.

As a young woman Lari says her father encouraged her and her siblings to pursue whatever career they wanted. But he often spoke to her of Pakistan’s urgent need for architects to build the new state.

When the opportunity arose, she applied to the Oxford School of Architecture (now part of Oxford Brookes University). Her cousin and future husband was studying at the same time at St Catherine’s College, designed by Arne Jacobsen.

They married in her third year and, incredibly, by the time she was finishing her architectural education she was the mother to a baby girl. She laughs away my astonishment at how she managed to juggle so much pressure, describing it as a “wonderful time”, and talks fondly of the attic flat they shared, as well as her husband’s enthusiastic and hands-on support for her career.

Lari returned to Pakistan and founded her practice in 1964. She says she has often been asked why she did not pursue an international career.

“I never really had the desire to be international,” she says. “My work is there [in Pakistan]. Your first thought was always for your country and how to help it flourish.”

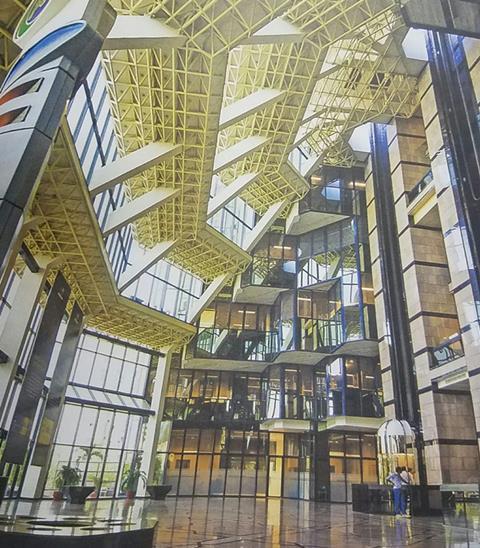

Of her hugely successful practice, Lari Associates, she says that at the time she took the approach that “the more iconic, the better it was. That was all I’d been taught. I indulged in that.”

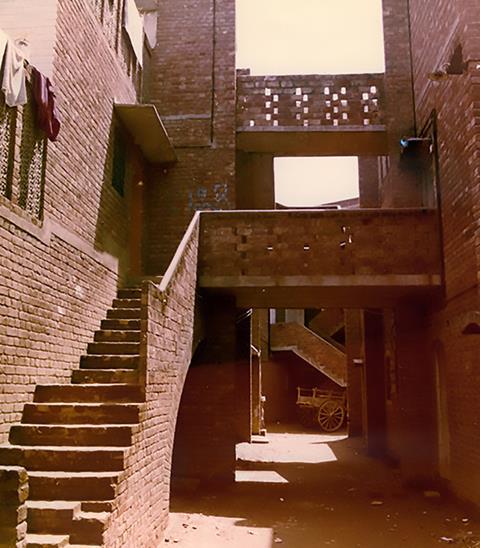

But despite the focus on big-budget commercial work, there were also notable social and affordable housing projects. During the quasi-socialist administration of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, she was appointed to design the Angoori Bagh Housing project in Lahore.

Rather than looking to high-rise precedents, Lari “drew inspiration from the old town of Lahore”. The design was based around how best to support women: “It’s so important to look at women’s needs and respond to that.”

The corporate sector is very heady, with money and resources no object

When asked what concerned them most, Lari says the women responded by asking “where their chickens would go”. So she included roof terraces that could accommodate the chickens – and provide play space for children.

She references Constantinos Doxiadis as a key influence, with his emphasis on places that facilitate organic growth and self-building. At the Lines Area Resettlement Project in Lahore, she adopted “small lots with incremental building” – an approach that would recur again much later in her career.

But, as socialism receded and Pakistan emerged as a key ally of the capitalist US in south Asia, Lari’s career became almost exclusively focused on commercial work. “The corporate sector is very heady,” she says, “with money and resources no object.”

“You get sucked into that whole thing,” she observes, before noting that much of the low-cost housing disappeared from the practice’s work. “Those ideas got lost in the late 70s and early 80s.”

Of this period in her life, she says she is now described as someone who “was a starchitect and is now atoning” and concedes: “I did enjoy it but didn’t know anything better.”

As her commercial practice wound down over time, she began to increasingly pursue her interest in heritage and architectural conservation. Her research centred on Pakistan’s historic architecture, including from its colonial era.

Lari describes becoming increasingly interested in “how to save British-era architecture”, which she notes was “quite unusual at that time”. She singles out the Indo-Saracenic designs of Samuel Swinton Jacob as being of particular interest.

Acknowledging the complexities of working in such a field, she believes that Pakistan understandably has a “love-hate relationship” with its colonial heritage, but points out that the British pioneered the academic study of the subcontinent’s ancient monuments: “They produced wonderful drawings of our own heritage.”

Her interest in conservation led to what Roaf describes as Lari’s “second career”.

Lari says: “I had retired and then UNESCO got in touch.” They wanted her to oversee the restoration of the fort in Lahore.

She describes the opportunity as a “wonderful privilege”. Working closely with UNESCO’s Ingeborg Breines, Lari was given the title of UNESCO “national adviser”.

The job provided access to Lahore’s historic records – “amazing stuff from the British era”. Lari realised there were “no drawings since the British period”, and began working to create up-to-date surveys of the fort.

“I’ve been very lucky in my life” she says. “I’ve tried to learn at every stage.” In the course of her conservation work on the fort, she discovered a fascination with lime.

I haven’t used any cement or steel since 2000

She describes it as “the most wonderful material” and states: “I haven’t used any cement or steel since 2000.” It has also become a key feature of her more recent work in disaster zones.

Of the conservation projects within the adjacent old walled city of Lahore, with which she was less directly involved, she says: “I think it’s very good conservation, but they’re gentrifying it and ordinary people are not involved.”

The Royal Gold Medal is approved personally by the Monarch, and this is the first to have been awarded since Charles III came to the throne. It appears to be a canny choice by the selection committee.

Looking back at her work over the past few decades, with its focus on architectural conservation, traditional building materials and zero-carbon, I am struck by how much of it seems to align with King Charles’s preoccupations.

Isn’t it strange that she is lauded by the RIBA for adopting these stances, while the King continues to be derided in most architectural circles in the UK?

Referring to the early days of Charles’s interventions, she says: “At the time, everyone thought, ‘where is he going’? What is he trying to do?” But she concedes that over time the relevance of a lot his views have become clearer.

She now sees those historic solutions to materials and climate “are very pertinent to today with climate change”.

Of her interactions with the King, she concedes that “he has been very supportive of my zero carbon work”. But that does not mean she is a convert to Charles’s stylistic preferences.

“Just replicating what you did before – that doesn’t work. I don’t try to replicate older structures or older themes.”

She derides what she calls the “instant Islamic” approach adopted by some Pakistani architects, as a superficial application of historic motifs.

Referring to historic buildings, she says: “I feel there is a lot there we can learn from. Tradition for my work is extremely important”.

Rather than replicating the appearance of a building, she recommends that “you understand the spirit of things – that is tradition”.

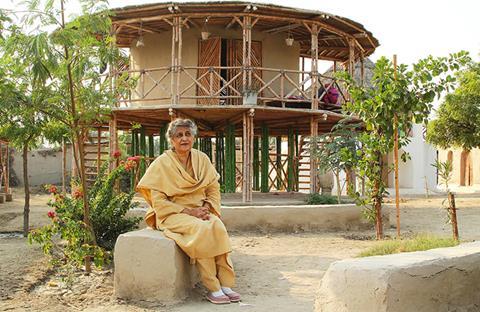

Lari’s “third” and most recent career has been focused on helping communities affected by earthquakes and climate change-induced disasters. She has pioneered approaches that eschew traditional donor-led solutions. And, in earthquake zones, she has promoted construction using the recycled debris from destroyed buildings.

“Every successive disaster taught me something,” she says. “That’s why architects must be on the scene. Not as a one off. That’s when you’ll learn.”

I ask how she feels about the future of Pakistan and the country’s architectural profession. “There are lots of issues with our country,” she says. “We’re floundering.”

I know it’s the young people who really want change, but how do we do it?

But she attributes the blame to the elites: “It’s nothing to do with the people. I think the people in my country are amazing. People at the top are corrupt – that’s the problem. That’s why I decided a long time ago not to work with the government.”

Of younger architects in Pakistan and the urgent need to address housing, climate and disaster resilience, she believes that “very few” are showing an interest and commitment to work outside of conventional forms of practice.

“Universities are still talking about making big shot architects. The other path is shrouded in all kinds of difficulty.”

Lari concedes that it is hard to earn a living on the kinds of projects on which she is now engaged. She sees it as an “issue for the whole profession of architecture”.

“I know it’s the young people who really want change, but how do we do it?

“We are not supporting young people to take a divergent path,” she complains, before arguing that architects need to be more proactive in initiating projects. “Architects wait for clients – I ask why? There is no dearth of design opportunities.”

On winning the Royal Gold Medal she is less focused on her personal achievement and more preoccupied with how to leverage this moment for some wider advantage.

She wants to “help young professionals on a divergent path” but worries whether “the profession is ready to support this?”

We discuss the way in which successful architects sometimes dabble in one-off commissions in disaster zones or impoverished communities, but that this only rarely becomes a core focus for those practices.

She wonders why the culture of taking on pro-bono work in the legal profession has not been more widely adopted. “Where’s the scaling up? They don’t adopt it as mainstream work.”

Lari’s commitment and optimism feels like a legacy of Pakistan’s early nation-building zeal. A faith in progress, modified and adapted to the contingencies and corruption of modern Pakistan. Is there a fourth career in the offing, I ask her?

“My dream today is to rehouse 3-4 million people displaced by the recent flooding in Pakistan.” She launched a project in December that seeks to rehouse households and put them on a sustainable livelihood at a cost of £140 per family or less.

There’s no dearth of workforce because they all want to learn. And they’re all making money

The approach seeks to meet the basic needs of the desperately poor – providing a one-room house, shared toilet, cooking stove, potable water, solar-generated electricity and the makings of further sustainable income – such as chickens.

Having struggled to get the backing she sought from the private sector or international agencies, she has now adopted a “zero donor approach”. Her model is based on the people themselves paying small amounts, and using their own labour, to incrementally improve their lives. “I want to be independent of everyone. No donors…”

“Brigades” of organisers and builders are trained up, each able to upskill another cohort. “There’s no dearth of workforce because they all want to learn. And they’re all making money.”

By next March she is hoping that half a million households will have rehoused themselves under their own steam. “Once I’m done with that, I’m happy. I think I should be done by then.”

Postscript

The Royal Gold Medal will be awarded to Yasmeen Lari during a celebratory dinner at 66 Portland Place on 13 June.

No comments yet