An important new book challenges the architectural community to embrace inclusivity and champion diversity, writes Kudzai Matsvai

Four years ago, the world looked on in dismay as Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds. Although this was not the first time institutional racism had transpired so violently and so publicly, something about this incident triggered a resurgence in support and action on behalf of the Black community as people across the globe proclaimed, “BLACK LIVES MATTER!”

The introspection prompted by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) renaissance led to all areas of society endeavoring to understand how white supremacist ideologies have influenced them, and architecture was no exception. Today, we see the ripple effect of the BLM advocacy of 2020 in full swing as our profession tries to mobilise around the topic of inclusion. Whether it’s about improving office culture, decolonising education, or diversifying the way we produce space, it seems that everyone is trying to do something to make things better.

The problem I have found in my work as an Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) expert in the architectural profession is that, because inclusion is such a broad and diverse topic, people often struggle with where or how to start understanding all the issues at hand. Furthermore, those of us who have received architectural training are often guilty of wanting to “fix” a problem before we fully understand it, which often leads to impositions and assumptions becoming our primary design drivers. So, where do we go from here?

It will never be possible to know or cover everything as an individual, and we must accept this as a limitation. However, what we can start to do is create centralised sources of shared knowledge to make it easier for us to understand each other. This ensures that, as a collective, we possess the range of tools and knowledge needed to design more equitable and inclusive futures. And we can start arming ourselves with that knowledge by getting stuck into Inclusion Emergency: Diversity in architecture, a new book by Grace Choi and Hannah Durham.

It is suggested that the book “can act as a starting place,” and that is exactly what it has positioned itself to be - a fantastic place to start. With a range of diverse voices in the industry educating on a variety of diverse identities, Inclusion Emergency ensures that we now have a holistic resource for those who are not well-versed in the complexities of diversity but are eager to learn.

It is, in its own right, a fantastic text covering not just the breadth of inclusivity as it relates to our profession, but also the depth and complexity that come along with this. The authors also point readers to additional resources they can be used to further explore the characteristics highlighted in the book.

One thing that Inclusion Emergency does extremely well is to lay out the scale of the problem as it relates to different marginalised groups across the UK. From learning that only 9% of housing in the UK meets basic accessibility needs, to discovering that, as of 2023, “there are only 15 active architecture students who are deaf,” I found myself constantly confronted with facts and figures that confirmed that this is, indeed, an emergency that we can no longer afford to ignore.

In reading about the hardships faced as they advanced through their careers, you cannot help but question where you have failed to step up for others

From the very first chapter on accessibility, all the contributors make a vital and timely shift of placing the onus to act from those afflicted to those complicit. This is done throughout the book as the authors display extreme candour, and this refusal to sugar-coat the problem forces the reader to sit, uncomfortably, with their own prejudices and biases.

In reading about the hardships faced as they advanced through their careers, you cannot help but question where you have failed to step up for others in the profession. It is imperative that we not only feel this but use it as fuel to act.

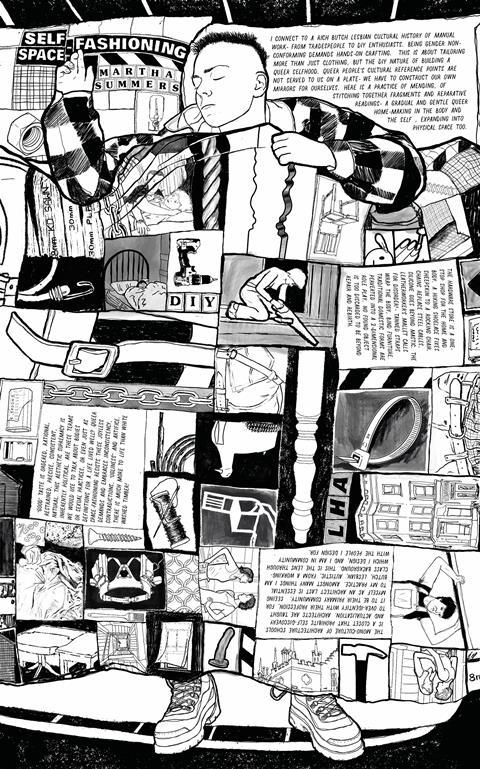

The addition of lived experience is perhaps the superpower of this book. By platforming individuals who are representative of the characteristics being explored, Inclusion Emergency takes a crucial step away from narratives of “giving voice to the voiceless” and instead empowers those with relevant experience to dictate how it is shared.

Hearing real-life accounts about how our profession, and as a result the built environment, fail to cater to so many people illuminates the harrowing reality of our current inclusion emergency. A special commendation must be given to all the contributors who, so beautifully, articulate their experiences as people from diverse backgrounds navigating the profession. Their honesty is admirable and will no doubt inspire countless others moving through the profession to speak and live their truths.

It must also be said that, because the authors do such a great job of contextualising the inclusion emergency against the backdrop of diversity around the UK by providing readers with up-to-date facts and figures, the book has an unexpected side effect of allowing one to appreciate how beautifully diverse this country really is. This drives home the feeling that, as built environment professionals, we have a duty to all these unique and wonderful perspectives and people.

The rigidity and inaccessibility of the accreditation process are called out and examined, with authors questioning if it remains appropriate for the increasingly diverse individuals seeking to join the profession. Additionally, we see many aspects of toxic architectural culture brought to the fore and questioned as barriers that impede progress. Things like proving dedication through all-nighters and regular mental breakdowns being considered a rite of passage are exposed as outdated and dangerous, and this is an important step in redefining the culture on which the profession is built.

Throughout the book, questions are also raised about our collective goals in diversifying the profession. Are we simply seeking more people with disabilities, non-white people, women, queer people, and other marginalised individuals so that they may take on the responsibility of championing these issues?

Will we one day find that we have moved laterally to a place in which architects with disabilities bear the responsibility of accessibility or women and non-binary people are pushed to look exclusively at gender disparities in the built environment? We must allow ourselves to unpack these pressing questions as we explore inclusion in the profession, and the book gives us ways of articulating and exploring these wider concerns.

Whilst it is important to highlight the harsh realities created by the inclusion emergency, the contributors strike the perfect balance of delivering the good with the bad. Whilst they do, rightly, focus on painting a vivid picture of the gross inequities that are at play, they also do a great job of providing us with information on where things are changing and moving forward, which helps to reinforce a sense of hope throughout the book.

As the book superbly demonstrates, it is the differences we all possess that strengthen the environments we create

This sense of hope is further cultivated as we see the authors unanimously agree on the fact that architecture can indeed be inclusive and equitable. They all write of its great potential to address and tackle the issues highlighted in the various chapters, and this reminds us that, although we are indeed currently in a state of emergency, change is possible, and, in many ways, inevitable.

The authors remind us of our collective responsibility to understand, implement, and champion inclusive design. The make-up of the profession will not magically diversify itself tomorrow, so all of us must develop an authentic relationship with diverse and inclusive design praxis.

We also receive a poignant reminder that being from a marginalised group is not the problem, but instead, the insistence of others to impose limitations, expectations, and ideas on those groups is. To be neurodivergent, queer, a woman, or to have a disability is not and has never been the issue. What has, however, remained the issue, is the refusal of society at large to see difference and, subsequently, include it.

After reading this book, I can only deduce that anyone claiming to be unaware of the inequities facing any marginalised group moving through or affected by our profession has chosen a stance of willful ignorance because the facts, figures, and first-person accounts are all right there. They do not just live in this book, either, but are also in the everyday lives of our colleagues, students, and even ourselves, we just have to be willing to listen.

Inclusion Emergency must become part of the pantheon of essential texts to be read by everyone as they move through the profession. Although we still have a long way to go in our journey to an inclusive profession, we will one day look back at this publication as a definitive turning point in that journey.

And to all those who will pick up Inclusion Emergency and resonate with its content, I leave you with these words by Janelle Monae who once said, “Embrace what makes you unique, even if it makes others uncomfortable.” As the book superbly demonstrates, it is the differences we all possess that strengthen the environments we create because difference allows us to look at the world around us from new and interesting perspectives, and it is those perspectives that are paramount to progress.

Postscript

Inclusion Emergency: Diversity in architecture, by Grace Choi and Hannah Durham, is published by RIBA Publishing.

Kudzai Matsvai is an equity, diversity and inclusion specialist, educator, activist and architectural designer.

2 Readers' comments