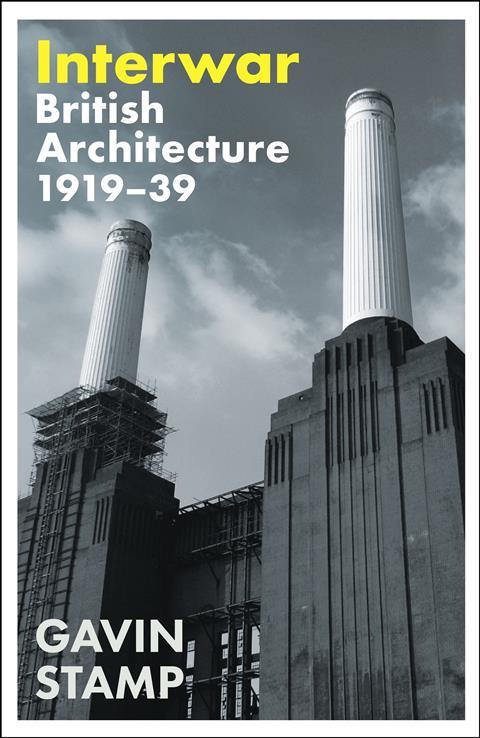

Giles Heather delves into the late Gavin Stamp’s exploration of the eclectic architectural styles that defined Britain between the wars

Gavin Stamp’s Interwar: British architecture 1919–1939 is a remarkable exploration of a contentious era in British architecture, shaped decisively by the trauma of the Great War. A scholar of this period when few others took an interest, Stamp provides a much-needed counterpoint to more conventional – and lazier – narratives that sideline other styles as revanchist cul-de-sacs off the shining highway to modernism. Rather, his approach gives equal weight to the eclectic array of architectural movements that flourished side by side, from Art Deco and neo-Georgian to the revivalist tendencies of the Tudorbethan, even stretching to Egyptian-inspired designs.

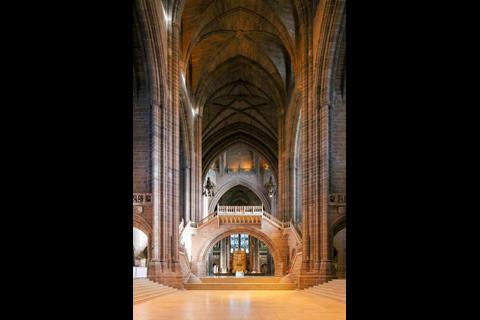

Stamp’s swansong, completed posthumously by his widow, the celebrated historian Rosemary Hill, highlights the restless diversity of this era, when architects, still grappling with the horrors of mechanised warfare, created memorials while also pushing the boundaries of design. In this regard, he shows that the cultural aftermath of the Great War revivified the symbolic resonance of classicism, where modernism struggled with metaphysics. The book opens with the sober image of Charles Sargeant Jagger’s Royal Artillery Memorial – a haunting reflection on war – and closes with Serge Chermayeff’s sleek modernist home, embodying a vision of a new form of Englishness. However, modernism is only one part of this intricate story. While it was emerging as a dominant force, Stamp takes great care to unpack the many other threads that characterised interwar architecture, celebrating their plurality.

Stamp’s writing is meticulous, full of wit, and deeply affectionate towards the buildings and architects he discusses. He doesn’t merely chart a history of styles but creates a portrait of a nation grappling with loss, modernity, and identity. His treatment of modernism is critical yet balanced – he acknowledges its growing influence but avoids lionising it at the expense of other, equally significant movements. His treatment of underappreciated styles, such as the neo-Tudor or the exuberance of Egyptomania, is especially insightful, showing that these often-maligned styles were as valid – if not more so – as a means of satisfying contemporary needs.

What stands out is Stamp’s ability to capture the emotional and cultural resonances of these architectural choices. He deftly contextualises designs like Edwin Lutyens’ Thiepval Memorial and Giles Gilbert Scott’s work on the Battersea Power Station, both symbols of larger social and technological shifts. Stamp’s particular admiration for Lutyens is evident throughout the book, though his affections are by no means limited to him alone. Oliver Hill, Robert Atkinson, and lesser-known architects like A.G. Shoosmith all emerge blinking into daylight under his critical gaze.

Interwar is, in many ways, a capstone to Stamp’s career. His deep engagement with the period, his critical pithiness, and his capacity to rekindle enthusiasm for obscure or forgotten works make this an invaluable contribution to architectural history. The accompanying photographs – many taken by John East – add another layer of richness to the text, offering a visual élan that complements Stamp’s stylish prose.

In the end, Stamp does more than recount the architecture of the interwar period; he captures the pulse of a nation in flux. His work is a testament to the diversity of British architectural thought and practice – a reminder that history is not only made by those presenting themselves as radicals but also by those who chose the less fashionable ways of tradition, continuity, and eccentricity.

The historical perspective, as Stamp so deftly shows, can be a far more acute and measured judge of endurance and worth; the canon of what constitutes architecture with a capital A is far broader than the polemics of an era could admit. With Interwar, Stamp – and the wonderfully seamless and skilful Hill – provoke us to start remembering the architectures of this period in detail, and to ponder whether tedious polemic might be altogether circumvented. There is certainly a comparative lack of architectural dogmatism today – perhaps someone like Patrik Schumacher can maintain, with a glint in his eye, that parametricism is the singular point on the canon, but few others are so apparently narrow. Even so, there is so much more work to be done, monographs to be written. It is our great loss that we no longer have Gavin Stamp to write them.

>> Also read: Brutalist Britain by Elain Harwood

Postscript

Interwar: British architecture 1919–1939 by Gavin Stamp is published by Profile Books.

Giles Heather is a director and co-founder of Goldstein Heather Architecture.

No comments yet