At least 18 major schemes are planned for a small area around Bishopsgate, including some of the tallest buildings in the capital. But how many will actually get built? Tom Lowe talks to some of the biggest players in the City’s commercial sector about what lies behind the latest cycle of development and what might hold it back.

Regular readers of Building Design will have noticed the considerable number of news stories about big schemes proposed in the City of London over the past year or two. It has seemed as though a shiny new tower or high-end refurbishment has been unveiled by developers or approved by councillors almost every week. Planning applications to the City of London Corporation were up 25% year on year at the end of 2023, and the pace only seems to be increasing.

In the past month alone, Building Design and its sister title Building have reported on plans for a 40-storey tower at 63 Camomile Street, a refurbishment of the Gherkin, revised plans for a 33-storey scheme at 70 Gracechurch Street and new proposals for a tower at neighbouring 60 Gracechurch Street. Some of the biggest schemes of the past year have included Eric Parry’s fresh plans for the 74-storey 1 Undershaft, RSHP’s 54-storey 99 Bishopsgate and Herzog & de Meuron’s £1.5bn redevelopment of Liverpool Street station.

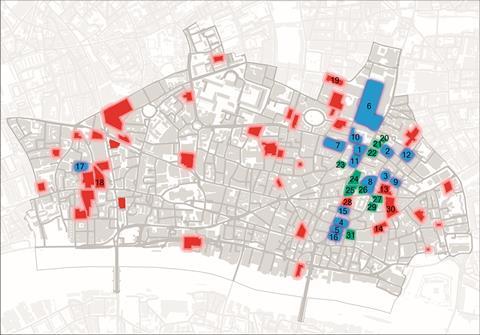

What is particularly striking is that the bulk of these schemes are squeezed into a relatively small part of the Square Mile, gathered around the cluster of towers that includes 22 Bishopsgate, the Gherkin and the Cheesegrater. At least 18 major schemes – most of them towers more than 30 storeys in height – are now being drawn up for a stretch of land running from Broadgate in the north, past Liverpool Street station, down Bishopsgate and ending at Gracechurch Street in the south. From conversations that Building has had with developers and consultants, it seems at least 10 more schemes in the area are also being developed but have yet to be made public.

If the construction timelines of the City’s commercial developers are to be believed, most of these schemes will be built over the next five years. This would transform what is already one of the busiest thoroughfares in London – anyone who has attempted to fight their way down the narrow pavements of Bishopsgate at rush-hour can attest to this – into one huge construction zone dominated by walls of hoardings for most of the rest of this decade.

Of course, it is highly unlikely that all of these projects will go ahead at the same time, partly due to industry capacity but mostly because of the limits of occupier demand in the market. Investors will not want to shell out the huge sums needed to build a major office tower without a reasonable expectation of turning a profit, and that becomes less likely if there are too many rival schemes going up simultaneously.

|

Announced |

Plans submitted |

Consented |

Under construction, nearing completion or completed |

|

1. 99 Bishopsgate Developer: Brookfield Properties Architect: RSHP Storeys: 54 |

6. Liverpool Street station redevelopment Developer: Sellar and Network Rail Architect: Herzog & de Meuron Storeys: 16 (above the station) |

10. 55 Old Broad Street Developer: Landsec Architect: Fletcher Priest Storeys: 24 |

19. 2 Finsbury Avenue Developer: British Land Architect: 3XN Storeys:

|

|

2. 63 Camomile Street Developer: Axa IM Alts Architect: Fletcher Priest Storeys: 40 |

7. 75 London Wall extension Developer: Castleforge and Gamuda Group Architect: Orms Storeys: 13 (three added) |

11. 55 Bishopsgate Developer: Stanhope and Schroders Architect: AFK Storeys: 63 |

20. One Bishopsgate Plaza - completed 2021 Developer: Stanhope Architect: PLP Storeys: 43 |

|

3. The Gherkin refurbishment Developer: Bury Street Properties Architect: Foster & Partners Storeys: 41 |

8. 1 Undershaft revised Developer: Stanhope Architect: Eric Parry Storeys: 74 |

12. 115 Houndsditch Developer: Brockton Everlast Architect: AHMM Storeys: 24 |

21. Heron Tower (110 Bishopsgate) - completed 2011 Developer: Heron International Architect: KPF Storeys: 46 |

|

4. 70 Gracechurch revised Developer: Stanhope Architect: KPF Storeys: 33 |

9. Bury House revised Developer: Bentall Green Oak Architect: Stiff & Trevillion Storeys: 43 |

13. 100 Leadenhall Developer: Frontier Dragon Architect: SOM Storeys: 57 |

22. 100 Bishopsgate Developer: Brookfield Properties and Great Portland Estates Architect: Allies & Morrison Storeys: 40

|

|

5. 60 Gracechurch Developer: Sellar and Obayashi Architect: 3XN Storeys: 30 |

|

14. 50 Fenchurch Developer: AXA IM Architect: Eric Parry Storeys: 35 |

23. Tower 42 - completed 1980 Developer: NatWest Architect: Richard Seifert Storeys: 47

|

|

15. 85 Gracechurch Developer: Hertshten Group Architect: Woods Bagot Storeys: 32 |

24. 22 Bishopsgate - completed 2019 Developer: Lipton Rogers and AXA IM Architect: PLP Storeys: 62 |

||

|

16. 55 Gracechurch Developer: Tenacity Architect: Fletcher Priest Storeys: 32 |

25. 8 Bishopsgate Developer: Mitsubishi Estate and Stanhope Architect: Wilkinson Eyre Storeys: 51 |

||

|

17. Hill House Developer: Landsec Architect: Apt Storeys: 20 |

26. The Cheesegrater (122 Leadenhall) - completed 2014 Developer: British Land and Oxford Properties Architect: RSHP Storeys: 48

|

||

|

18. 120 Fleet Street Developer: Chinese Estate Holdings Architect: BIG Storeys:21 |

27. The Scalpel (52 Lime Street) - completed 2018 Developer: W R Berkley Architect: KPF Storeys: 38 |

||

|

28. 1 Leadenhall Developer: Brookfield Properties Architect: Make Storeys: 36 |

|||

|

29. The Willis Building - completed 2008 Developer: British Land Architect: Norman Foster Storeys: 28 |

|||

|

30. 40 Leadenhall Developer: Henderson Global Investors Architect: Make Storeys: 35 |

|||

|

31. The Walkie Talkie (20 Fenchurch Street) - completed 2014 Developer: Landsec and Canary Wharf Group Architect: Rafael Viñoly Storeys: 40 |

What is now underway in the City is a race between some of London’s biggest developers, including Stanhope, Sellar and Brookfield to get to site first. It constitutes the latest wave of potential development in the City, following the last big cycle in the years leading up to the pandemic which saw the construction of Lipton Rogers and Axa’s 22 Bishopsgate, currently the tallest in the cluster.

While the last few years have been relatively subdued because of a prolonged period of economic uncertainty and inflation, developers now believe that a corner has been turned.

There’s certainly going to be a real transformation in the City in the years to come. Demand is returning

Richard Garvey, development director, Sellar

“There is really positive momentum in the City,” says Dan Scanlon, UK president at Brookfield Properties, the developer behind 99 Bishopsgate. “We’re coming into a cycle where there’s good active demand. And there’s good rental growth evidence for best-quality spaces, so there will be a number of developments that will come forward.

”That’s a really positive thing for the City, given that new construction starts in recent years have been limited.”

Richard Garvey is development director at Sellar and the firm’s project lead on the redevelopment of both Liverpool Street station and Seal House in the west of the City. “There’s certainly going to be a real transformation in the City in the years to come,” he says. “Demand is returning.”

What appears to be different about this cycle is the size and height of the schemes. Across London, there is now a “roaring” market for grade A office space, fuelled by strong flows of overseas investment and a supportive planning environment, according to New London Architecture’s latest Tall Buildings Report.

Previous phases of development tended to see smaller, mid-rise schemes spread out across the City, but the top-tier space now leading the market is being supplied in glamorous looking office towers, which have replaced residential towers as the biggest driver of high-rise construction in the capital.

“There’s a greater expectation for the quality of office space and the quality of the amenities, and towers can deliver on that,” Scanlon explains. “They get great views, great daylight and capacity for flexibility.”

The City is now the only part of London where the height of towers is increasing, according to the NLA. But due to planning restrictions protecting views of the Square Mile’s three most important heritage assets – St Paul’s Cathedral in the west, the Monument in the south and the Tower of London to the east – there are only two locations where developers can build tall.

They can choose either the cluster around Bishopsgate, where heights are capped at 300m, or a smaller, more restricted zone north of Fleet Street, which has a limit of 100m.

A handful of major schemes are planned for the western cluster, including Landsec’s 20-storey Hill House scheme, due to be built by Skanska, and the stalled 120 Fleet Street block expected to be built by Lendlease. But the real hub of activity is the eastern cluster, which Garvey says is set for a “really quite striking” amount of development over the next 10 to 15 years.

So if not all of the 18 potential schemes in the area can go ahead at the same time, which ones are most likely to be built? Steve Watts, director at Turner & Townsend Alinea and chairman of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, says it is just as much about the project team and procurement strategy as the scheme’s basic viability.

“One of our mantras has been that you have to sell your project and your team to the market,” he says. “The best projects and the most attractive projects not only to future occupiers, but also to the supply chains will be the ones that proceed more quickly.”

There has always been a limited pool of specialist and main contractors able to take on big towers, with Multiplex, Mace, Skanska, Sir Robert McAlpine and Lendlease being the only real players in the market. Given the extremely high cost of commercial tower projects, these firms tend to want to limit their risk profile and so are selective about what schemes they take on.

Multiplex is actively tracking only 11 of the 18 schemes currently being worked up, these being the ones which it sees as the most likely to be brought forward in terms of their viability. Stanhope’s 1 Undershaft – the tallest of them all – is expected to cost more than £1bn to build, about half the turnover of a firm such as Mace, so the stakes for contractors are high, especially on fixed-price deals.

Talks are currently underway throughout the Square Mile as developers weigh up the best way to build out their schemes. Construction inflation over the past few years and a lingering uncertainty over how robust demand for office space will be in the future means that investors have increasingly wanted the supply chain to underwrite more risk with fixed-price deals. This can be a hard sell in the current market.

Another £1bn tower scheme, across the river in Southwark, is 18 Blackfriars. Multiplex and Mace are intrested with the latter, along wth Lendlease and McAlpine, thought to be eyeing the work only if it is let on a construction management deal, which shares the risk on costs with the developer. One source told Building that the job is “too big for design and build”, and the same concerns are likely to apply to many of the schemes in the City.

Watts says the client and consultant team is the number one factor for getting contractors to put pen to paper. “A client who has got a good track record, who employs… a project manager, a design team, cost consultant, which all have experience in those sorts of projects, and with whom the key players in the supply chain have a good relationship and know that they know what they’re doing.”

But although contractors may be more inclined to opt for safer construction management deals on the biggest schemes, Watts is seeing a greater appetite for risk taking among the big players as construction material inflation slows. “Main contractors are a little happier, their appetite is a little greater, they are more willing to look at projects that perhaps would have been one too many for them 12 months ago.”

Even if a client gets a contractor on board, there is the rest of the supply chain to worry about. There are only really four firms that can deliver the concrete work on big towers – Keltbray, Byrne, Careys and Morrisroe. For steel, only Severfield, William Hare and the smaller Bourne can do the complex structural work, and the market for facade contractors is even more constricted.

If all 18 schemes around Bishopsgate go ahead, it would be “very, very unlikely that the UK market could respond to it”, one industry source says. This is less about the skills available than it is about the materials themselves.

“You’re not talking about stretching the capability of some individuals or groups of individuals. You’re talking about manufacturing capability, you’re talking about actual physical facilities. You can’t switch an extra one on overnight. If somebody said they need a new steel fabrication facility, that is a two to three-year process to do that.”

Another issue is the highly restricted sites in this part of the City. Many of the schemes in question directly neighbour each other and would be built at the same time if everything goes to plan. These include Brookfield’s 54-storey 99 Bishopsgate and Stanhope’s 63-storey 55 Bishopsgate, both scheduled to start construction within the next two years.

They sit on a crossroads between Bishopsgate and Wormwood Street which is at the centre of the new crop of high-rise proposals, with 63 Camomile Street and 55 Old Broad Street also being lined up for the area.

About 200m down the road there is a row of four planned towers at 55, 60, 70 and 85 Gracechurch Street. At peak construction you could have more than 200 vehicle movements a day for the larger towers, so planning construction vehicle movements and road closures if neighbouring schemes go ahead at the same time will be a headache for everyone involved.

“In essence, you’re significantly increasing the volume of traffic that would be in those areas, and it’s heavy traffic,” one source says. “So that will in itself create problems.

“It would cause significant disruption and make those projects significantly more difficult to deliver if there were a number of them concurrent with each other.”

I’m anticipating within the City we will be able to facilitate the construction of these towers in a manner that is not problematic

Dan Scanlon, UK president, Brookfield Properties

Brookfield’s Scanlon is relaxed about the implications of this for 99 Bishopsgate. The firm is nearing completion on the 36-storey 1 Leadenhall, which is adjacent to Stanhope’s 50-storey 8 Bishopsgate which finished last year.

“They’ve been going alongside each other for the best part of three years with minimal disruption to the street,” he says.

“You have sophisticated developers and expert contractors who are regularly liaising with each other to make sure that there’s a planned strategy for the network of vehicles and lifting and road closures. I’m anticipating within the City we will be able to facilitate the construction of these towers in a manner that is not problematic.”

One industry boss working on several big tower schemes in the City is not so sure. “I very much doubt developers are talking to each other to mitigate these things,” he says. “They might say that they are, but they’re not. They’ve all got a vested interest in being the first onsite or having their market timing.”

Before a scheme can start it needs to have a traffic management plan approved by the City. If one scheme has this secured, a neighbouring scheme will find it harder to get the sign-off they need at a time of their choosing, which will affect the scheme’s viability.

“You’re not going to get approval from the City transport people if the project site next to you is fully live, and then you want to double the traffic to that area and you want a pit lane as well,” the source says.

“You’re not going to get it. You would need to think of alternatives on a different street and that might be impossible with the sites that we’re talking about.

“It’s a race for them to get started and secure resources,” they continue. “It’s a race for them to secure approvals to allow them to go ahead because it may be, if they get the approvals before another, they’ll actually achieve a number of things that will stop the other one getting the approvals.”

One option for clients is simply to delay their scheme or do nothing, and this is a perfectly good option. Some in the industry suspect that many of the planning applications for sites in the cluster are just intended to increase the value of an asset so that it can be sold on, with the developers having no intention of building the scheme themselves.

Many would say this is no bad thing. A notable feature of the 18 planned schemes is the lack of statement designs with enough recognisable character to earn them a nickname from the public, like the Gherkin and the Cheesegrater.

Eric Parry’s 1 Undershaft, previously dubbed The Trellis, has been redesigned as a relatively conventional looking tower, a design which was recently criticised by Historic England for failing to do justice to the prominence of its role at the peak of the cluster.

Of all the proposals, only 99 Bishopsgate, designed by Cheesegrater designer Graham Stirk – the “S” in RSHP – and maybe AFK’s 55 Bishopsgate come close to having designs which differentiate them from any other glass and steel tower.

But for developers, and for the City, which has consciously tried to calm down its skyline, this approach looks like the way forward. “I remember Stuart Lipton saying to me, probably 10 years ago, not every tower can be a perfume bottle,” Watts says.

Lipton’s 22 Bishopsgate, which notably lacks a nickname despite currently being the City’s tallest tower, seems to have set a trend.

The Square Mile’s more charismatic towers were part of an “era of irrational exuberance”, Watts says. “Everyone did try to be a perfume bottle… Now, it’s a lot more nuanced than that.

“You’ve got to think about how the building is going to be used, a much richer mix of amenities, this sort of blurring between the private and the public and the activity of the ground for spaces, and social value.”

For those that like the idea of a cluster of perfume bottles in the City, they may be disappointed. But it seems equally as likely that only a handful of these towers will actually get built at all. We can only watch this increasingly congested and competitive space.

3 Readers' comments