As Jan Kattein Architects unveils its latest project at Westminster’s Church Street Triangle, Mary Richardson takes a closer look at the work of this innovative firm that weaves social practice into its inspiring and colourful placemaking

Known for his inventive approach to public-realm regeneration, Jan Kattein has built a practice around small-scale but high-impact interventions that blend architecture, social engagement, and sustainability. From high-street revitalisation to community-led placemaking, his work seeks to transform overlooked urban spaces into hubs of activity and opportunity. BD sat down with Kattein in the zinc-clad café at his latest project, the reimagined Church Street Triangle in Lisson Grove, Westminster.

Church Street Triangle and masterplan

At this London crossroads, two sharply contrasting neighbourhoods rub up against each other: to the east, the expensive shops of Lisson Grove’s antiques quarter; to the west, working-class Church Street, with its long-standing traditional market set within one of the UK’s most economically challenged wards. At their meeting point lies the Church Street Triangle, a small but significant public space shaped by the social and economic contrasts surrounding it.

The wider area is undergoing redevelopment under Westminster Council’s Church Street masterplan. But masterplans can take decades to fully come to fruition. In the meantime, the council identified the small square where these two worlds collide (only notable feature: boarded-up mock-Tudor toilets on a traffic island) as ripe for redevelopment. The aim was to facilitate communication across the social divide and to give locals a short-term win while the masterplan rollout continues.

>> Also read: Bringing dignity and joy to later living: Mae’s Daventry House project sets a whole new standard

>> Also read: How a team including LDA, Bell Phillips, DMA and Mae are writing a new chapter in Westminster’s council housing story

The solution Kattein’s team has come up with is to move the road – to enfold the refurbished toilets, complete with a new café addition, into the square – and to add new seating to encourage people buying lunch at the market to linger, sit and eat. Public toilets matter – better yet if they are quaint and half-timbered – so that’s already a win for the scheme. Plus, the café addition, operated by an asylum-seeker-run coffee company, is not just a new destination but also provides oversight of the public space.

New seating is made of snaking gabions filled with reclaimed cobbles from the rerouted road and old tiles from the toilet roof, topped with turquoise metal seats. These also double as stalls for the occasional outdoor antiques market – and improvised play equipment for passing children. Even on the cold day we were there, people were sitting eating lunch.

Affordable workshops

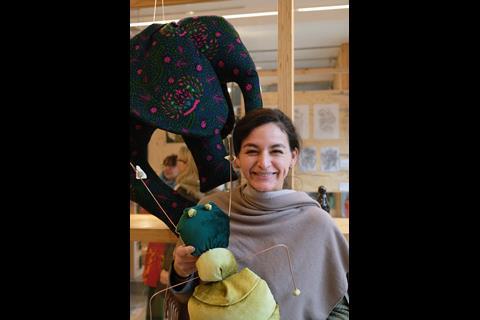

Another key element of the scheme is Triangle Studios, a new space offering affordable studio, workshop and retail spaces for local small businesses and creatives, run by Arbeit Studios. Newly ensconced tenants include Ashley, who artfully renews old trainers, and Vanessa, who makes sublime giant stuffed animals.

Kattein explains, “It was a former furniture showroom called Kiki’s that many locals recall with affection. But after that closed, the space was too large for any one business to afford to rent, so it remained empty for ages. We’ve divided it into small maker units, with a large communal area where local artists can show their work.”

The refit is lo-fi and sustainable, with oriented strand board and glass used to divide the space, leaving the bare bones of the original shop on show – repairs, dents, patches and all.

Par for the practice

The Church Street Triangle represents two types of work that Kattein’s practice has become renowned for: small-scale but highly considered publicly funded interventions in the public realm, and high-street regeneration. His is the opposite of statement starchitecture – a humble world of social architecture and modest physical interventions with large human impacts.

Kattein’s approach aligns with practices like Peter Barber Architects, where he began his career, sharing a commitment to socially driven design and community-focused projects.

Kattein grew up in Bonn and studied architecture at the Bartlett under Barber before going to work for him. Then, before starting up on his own, he worked for a couple of years as a theatre set designer in Germany.

Leyton High Road

By 2012, Kattein was back in London, and one of his first high-street regeneration jobs was the celebrated makeover of Leyton High Road ahead of the Olympics. This saw shops on the down-at-heel Waltham Forest high street repaired and repainted in bright colours to create a cohesive, attractive streetscape using “Olympic money”. (My favourite is the stone-cladding-covered pound shop that gained a multicoloured patchwork coat.)

Kattein recalls, “Working with East, we did a stretch of nine shops first. The council came back and said, ‘We like it. Can you do the rest of the road in time for the Olympic torch relay in four months’ time?’” He smiles. “We had to cancel annual leave and work round the clock, but we made it happen.”

It wasn’t just a question of tarting up the shops – pavements were repaired, and shop owners were offered business advice. Importantly, preliminary work involved getting business owners together and explaining that they were all in this together – with the goal of making their street an attractive destination. That meant no room for egos and individual decorative flights of fancy. In the end, only one shop declined to participate. Walk down Leyton High Road today and you can spot it – as much of a stand-out as that other infamous East End holdout, Spiegelhalter Gap.

The work was done in time, the torch relay came through, and photos of the newly decorated, bright, attractive street were beamed around the world. “Not that anyone realised it was anything to do with us,” says Kattein somewhat ruefully.

The rest of the world may not have realised, but those in the know in the capital took note. Since then, the firm has done 30 high-street reframing projects across London.

Reinventing the high street

But the brief has changed subtly in the years since that Olympic paint job, Kattein explains. His take on high-street reinvention has evolved along with the times – and the retail environment. “The Greater London Authority has encouraged us to take a creative approach that includes thinking not only about refurbishing but about what we do with empty shops – and, equally, how we serve the needs of those who don’t have money to shop. And about how we can bring social purpose into the high street too.

“High-street retail is shrinking,” he continues. “So, we need to think about how we can continue to drive footfall. And one way is to bring in workspace.” To that end, JKA has built temporary workspace units for rent at many different London sites, from Sayer Street in Elephant and Castle to Angel Yard in Edmonton.

Micro retail units

Micro retail units are another solution that has worked well for them. Kattein explains, “It’s not just that retail is receding, it’s also that retail is changing. There are loads of great businesses out there that just want tiny little retail units because they have a dual business model where they sell both online and on the high street. Selling on the high street doesn’t make them much money, but it gives them credibility. At the same time, it can help keep the high street alive and busy.

“This model has worked incredibly well at Blue House Yard, a collection of tiny little make/sell spaces we worked on in Wood Green, which are below the business-rate threshold.”

Embracing colour

The tall, narrow, brightly painted wooden sheds at Blue House Yard draw heavily on British vernacular, combining the form of Hastings net-drying sheds with the colour-washed charm of Finchingfield cottages. Uplifting bright colours are a signature aspect of the JKA brand.

At Switchboard Studios in Walthamstow, working in partnership with Meanwhile Space – through a joint enterprise called High Street Works – JKA divided up a former council call centre to make larger workspaces suited to more established businesses. The trademark refit style of stripped-back, warts-and-all original structure plus timber partitions again ticks budgetary and sustainability boxes.

Meanwhile spaces

Meanwhile spaces are another key strand of work in Kattein’s portfolio. The practice has a long and ongoing relationship with charity Global Generation, which uses disused London sites for temporary sustainable gardening projects with community-building, outreach and educational aims.

Skip Garden

The first iteration of this work was the much-lauded Skip Garden in the King’s Cross redevelopment, which cleverly saw vegetables grown in skips that could be moved around the masterplan as different parts of the site were developed. Its final iteration in Tapper Walk was designed and built by students from the Bartlett, where Kattein himself has now taught for more than 20 years.

The pièce de résistance of this project was his student Rachael Taylor’s cube-shaped classroom-cum-greenhouse, made from an apparently artless hotchpotch of discarded windows assembled into a striking, unconventional structure. It had the appearance of a patchwork of domestic extensions reimagined with an environmentally conscious purpose.

Paper Garden

The firm has subsequently worked with the charity on other interesting garden projects. At the Paper Garden, another wonderful structure – featuring more discarded windows – was born when the group was granted temporary use of the huge, disused paper store at the Daily Mail’s former printworks in Canada Water.

As Global Generation is primarily a gardening project, they took the roof off most of the large warehouse so that the space could be used for growing. Then they built an education centre in the remaining slice of the warehouse, using cordwood for the walls (Epping Forest coppice prunings set in lime mortar), floors made from 200 doors from a police station that was being demolished nearby, plus a load of differently shaped windows donated by Nordan.

“This is the most inclusive kind of community build,” says Kattein. “Even small children can have a go at cordwood because logs are light, so it doesn’t matter if you drop one on your toe. Not like bricks.”

Theatrical quality

The resulting bold red, multi-windowed structure has something of the stage set for a modern fairytale about it. In fact, his time as a theatrical designer has clearly had a large influence on Kattein, as an abstracted, emblematic, stage-set-like quality can be seen in many of his designs. The high-street makeover schemes often give a ‘theatre of life’ backdrop.

The latest joint venture with Global Generation is finally witnessing the creation of a permanent home for the charity at the Triangle Garden in King’s Cross. Kattein beams excitedly as he relates how many hundreds of volunteers have got involved in making wooden shakes and bricks, and trying their hand at CobBauge for the onsite builds.

Sustainability

Sustainability plays an increasingly important role in all the firm’s work. Kattein describes his practice as “socially and environmentally regenerative architecture”, which seems like a wholly apt appropriation of the in-vogue term. A desire to not contribute to construction’s carbon crisis has led Kattein to conclude, “Sometimes the right thing to do is not to build anything at all.”

On the firm’s website, he writes: “If we address each brief with an open mind, reserving judgement on the proposition – and indeed on whether a building is actually needed – until we have thoroughly engaged with and understood the place in question, we may find that a transformational impact can be achieved with limited means.

“The environmental crisis requires us to reconsider not just what we design, but also the very design process itself. As a result, when judging design quality, thoughtful and inclusive engagement with a place and its people is just as important as the visual and technical sophistication of the final outcome.”

No-build projects

In that spirit, the practice is able to lean into its existing strengths in social practice to pioneer a new ‘less physical building, more network building’ model, to deliver projects like the Wandsworth Food Bus. This no-build scheme consists of a refurbished bus that delivers low-cost, nutritious food to food deserts in the borough.

Co-design

Kattein’s method of co-design doesn’t involve asking residents what they want. “They’re likely to say more police and cleaner streets, which aren’t things we can deliver anyway,” he explains. Instead, his team asks people “how they live their lives; what their struggles are; what their hopes are; what their interest in a place is. Then you can respond to that and enlighten them about what they could have. You can then come back and say, ‘Well, you said this, and we thought of this. What do you think?’ And it opens people’s minds.”

Libraries

As BD is about to leave, Kattein says, “Oh, we haven’t talked about libraries yet!” As one of the few remaining non-commercial, indoor public spaces – and one that is often not operated in a way that makes use of its full potential as a community asset – the library is one of his new passions. Kattein has spotted a new opportunity to do good, using existing infrastructure.

At the Fore Street Library in Enfield, using Good Growth Fund money, his team has retrofitted new fixtures and fittings to the library to enable it to fulfil a role as a community and arts venue outside its normal limited opening hours. A community group, Fore Street For All, has earned the trust of the council and now runs a wide range of activities, from jazz nights to bingo and yoga – programmes that were once common in community centres before many were closed. A similar trick has been pulled off in Cambridge. So, watch out, librarians of the UK – Kattein is coming for you! And he’s got his eye on your underutilised assets.

Activist, inventor, arbitrator

On the subject of books, Kattein set out his architectural philosophy in his first book, The Architecture Chronicle: Diary of an Architectural Practice, which delved behind the glossy finished-project photo to get to grips with the nuts and bolts of the messy process of building design. In it, he identified three key roles for the architect: as activist, inventor and arbitrator. His thesis is that without the ability to perform all these roles, an architect (or team) will fail.

Kattein himself has mastered all three roles, it seems, and carved out yet another for himself: that of architect as catalyst – for he and his 11-strong team are surely precipitating rapid, almost alchemical, social change as they deliver considered schemes that serve as vessels for life-changing opportunity in some of the most unprepossessing corners of urban London.

Architect as grant applicant

A sceptical observer might point out, “But it’s all taxpayers’ money!” And largely, it is – JKA are evidently also highly skilled ‘architects as grant applicants’.

But surely only the most hard-hearted of small-state-ists would quibble at this use of public money to kickstart change by making neglected urban backwaters more attractive – and useful – to the communities who live in them. Kattein is building frameworks, and accompanying networks, within which innumerable lives can be improved. And good-looking frameworks at that. There is a joyous light-heartedness about the look of JKA projects that belies their deadly serious intent: to change lives for the better.

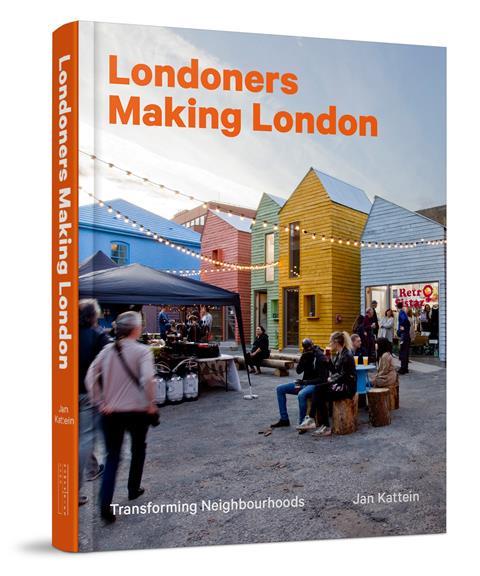

Kattein’s latest book, Londoners Making London, reminds us that architecture is not just made by architects. It is a fascinating collection of interviews with instigators, community activists, campaigners and self-builders who share the methods, tricks and strategies they have used to transform their neighbourhoods for the better.

Sarah Simpkin’s review for Building Design explores how Londoners Making London captures a sense of agency often absent in mainstream architectural narratives.

One of the key takeaways from both Simpkin’s review and the book itself is that these projects do not emerge in a vacuum. They rely on networks, knowledge-sharing, and often the sheer tenacity of individuals and community groups in navigating bureaucratic hurdles.

>> Londoners Making London: ‘There is a gap in physical space that creative, determined people fill’

Postscript

No comments yet