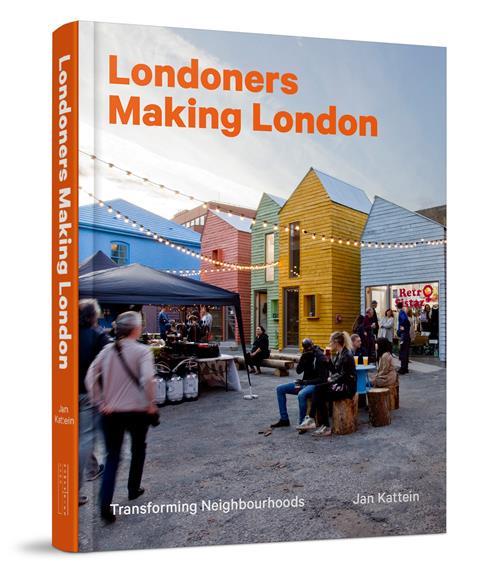

From gardens to garment academies, Londoners Making London highlights grassroots projects reshaping the city, writes Sarah Simpkin

Jan Kattein’s new book, Londoners Making London is not about architects, sorry, but brings together nine stories of entrepreneurs, activists and community groups transforming their own neighbourhoods.

My copy arrived, appropriately, on local election day in May. A democratic process that relies on being able to procure available community space. For a general election, we need 40,000 polling stations across the UK, to be roughly precise, along with 150,000 polling station staff. But according to Locality’s Save our Spaces campaign, on average, “more than 4,000 publicly owned buildings and spaces in England are being sold off every year.”

In every aspect of life in London, from the logistics of voting to building homes, there is a gap in physical space and services that creative, determined people fill. And it’s this gap that the book explores. It looks at projects where people, here mostly women, have identified a need, whether for somewhere to live, work, make or grow, and have done something about it – in the process fulfilling less tangible desires, like togetherness and visibility.

There are four themed chapters, each with two or three illustrated interviews. Kattein asks a few thoughtful questions, but for the most part it’s an unedited testimony of each project – an aspect of the book I quite enjoyed. It doesn’t gloss over the details of how things like a school library get funded, or that there were 32 conditions to planning permission. The stories also make a strong case for the value of a network. Many projects were helped along by a casual remark in a meeting, someone that knew someone, or an idea that didn’t quite happen but became the spark for a different opportunity.

The book starts outside with gardens, and with Sitopia Farm, which covers two acres of the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The farm is illustrated with a sundown photo of the kind of long communal table for a hundred or so that could be a Tuscan wedding. You wouldn’t think it was just off Shooters Hill. Behind this bucolic image is the story of a civil servant, Chloë Dunnett that wanted to be a farmer and use organic, regenerative principles to produce food and flowers for local people and businesses. She explains the method in the scenic setting: “We want the spaces to be beautiful because we want people to come and connect to the land, and each other. The flowers really help with that. Society, or at least the market, seems to value flowers more… they can generate more profit and help cross-subsidise the vegetables.”

The section on Enterprise + Learning features a new school library, an academy for garment making to increase skills and manufacturing in the UK, and Church Grove community-led housing. All projects for which the initial transformation will bring much broader, longer-lasting benefits in employment and education. There are architects in this latter project too, if you were missing them. Kattein interviews Jon Broome, design advisor to and member of the Church Grove project board.

The council has been supportive of this development, but the group had to work hard to communicate and demonstrate the value of their proposal. Broome associates this with a lack of knowledge of Lewisham’s previous self-build schemes, such as Walter’s Way, and a way of thinking perhaps lost with the in-house architects. He remembers working for the council after leaving college when there were “300 people in the architects’ department… There’s not one architect employed by the council now.”

The tension between a council acting as instigator, ally or obstacle is a theme that runs through the book; their remit can be unclear and the impact of local activism varies by area. Outside London recently, campaigners celebrated planning success for The Phoenix development in Lewes. At the same time in Totnes, Devon, an ambitious community-led scheme, the Atmos Project, was thwarted by planning following the sale of the site to a private company.

Although the book highlights people bringing about change, it’s a reminder that we rely on London’s boroughs to be inspired patrons and enablers in the face of privatisation

A section on Building + Making looks at how Maxila Men’s Shed turned a former nursery under the Westway flyover into a space for tinkering and making friends. This chapter is the first to directly reference one of Kattein’s own projects, Blue House Yard in Wood Green. Still however, the focus isn’t on the design of the space so much as the systems that enabled it.

To build the project, the architect and Meanwhile Space Community Interest Company set up their own construction firm to cut the lengthy public procurement process, thus allowing for volunteering and training opportunities. There’s an interesting point in here too on the value of demonstration in building momentum; painting the building bright blue early on sparked local interest in the site, and volunteering on the build led to some people ultimately becoming tenants.

The book ends with a look at temporary use and events, such as the African Street Style festival in East London, which has become a hugely popular annual celebration. Here urbanist, Jeffrey Lennon identifies another gap that this kind of activism fills, and a lack of definition: “local authorities find it difficult to know where their role stops. And then whose role is it to make these types of events happen? Should the local authority manage street festivals? Or do they trust local people?”

The final interview is with CEO of Be Enriched, Kemi Akinola. Her project, the Food Bus provides affordable, responsibly-sourced healthy produce in the capital’s food deserts, “not food aid, a more low-cost alternative to the supermarkets.” The top floor of the double-decker functions as a café and mobile community space. A model with potentially even greater value in car-dependent rural communities. This last project shows most acutely the extent of the gaps that dedicated people are helping to fill. Not small cracks in many of these cases, but basic needs: food, mental health support, education, a home.

Although the book highlights people bringing about change, it’s a reminder that we rely on London’s boroughs to be inspired patrons and enablers in the face of privatisation. But they can only be as effective as their budget and the social contract between local government and residents.

Jonathan Carr West of LGIU sees local authorities as facilitators that “pull together the strands – growth, services, delivery, engagement – and give people a stake in their places. But… local government is prevented from playing this role to its full potential… hindered by financial constraints… and declining levels of trust in political institutions.”

These case studies are useful evidence for what can work, what happens when assets aren’t sold off and local people take control; useful reading for those working in government as much as grassroots organisations.

And of course, there are many great projects that could have been in the book had there been space – and not just in London. Jane Riddiford of Global Generation talks about visits to Pertwood farm in Wiltshire, Jenny Holloway of Fashion Enter touches on their manufacturing sites in Leicester and Wales. Perhaps starting points for Kattein’s next journey and a sequel.

Postscript

Sarah Simpkin is a writer, communications consultant and Londoner. Londoners Making London is by Jan Kattein, published by Lund Humphries.

No comments yet