Mary Richardson meets the research and design practice advocating for bio-based materials such as hemp, straw and unfired clay as alternatives to carbon-intensive construction. But, as the industry faces mounting pressure to decarbonise, can these approaches be scaled up to meet real-world demands?

The construction industry is at a crossroads. While sustainability is now central to industry discourse, mainstream solutions often fail to address the full environmental impact of building materials and processes.

In particular, there is a growing recognition that whole-life embodied carbon – the emissions associated with material extraction, production and construction – is just as critical as operational carbon over a building’s lifetime. As the sector grapples with the urgent need to decarbonise and meet net zero targets, a growing number of architects, designers and researchers are pushing beyond conventional green building strategies to explore deeper, systemic change.

Among them is Material Cultures, a practice on the cutting edge of decarbonisation, working with the kind of innovative, plant-based materials and techniques that the built environment will likely need to embrace.Their work challenges assumptions about materiality, circularity and scalability – raising crucial questions about what a truly post-carbon built environment might look like.

BD spoke to co-founder George Massoud to learn more about the practice’s current work and its vision for the future of deep green, post-carbon building design.

Sustainable construction is the only game in town these days, and everyone talks up their low-carbon credentials. But there is a wide gulf between net zero targets and current ways of working – which is why the experimentation of pioneer practices like Material Cultures is so important.

Material Cultures works in that contentious space between good environmental intentions and current construction practice. And they are not afraid to get their hands dirty – often quite literally – doing the messy work needed to translate environmental aspirations into practical, applicable ideas.

Origins

The east London-based not-for-profit practice undertakes building design, materials research and education, all focused on what they term “regenerative construction”. The team of 10 is led by Massoud, Paloma Gormley (daughter of the sculptor Antony), and Summer Islam.

The firm was formed when the three co-founders merged their two practices, somewhere around 2020, though the exact date of the first Material Cultures project is not 100% clear as all three were already sharing workspace and collaborating on projects.

Manifesto

This is an earnest and passionate practice on a mission to tackle construction’s serious climate crimes. For Material Cultures, current construction practices constitute an “oil vernacular” – a way of building that relies unhealthily on cheap fossil-fuel energy and fossil-fuel-derived materials, and is also engaged in an unwinnable war against permeability.

And they have a manifesto – their recently updated book, Material Reform: Building for a Post-Carbon Future – to guide them as they do this, and to act as provocation and inspiration for others. For anyone wanting to deepen their understanding of what is wrong with current practice and learn about potential fixes, of varying levels of practicability, it is a must read.

Their website is also a trove of interesting research about everything from new models of forestry and ways of using native timber to how bio-based construction could be rolled out in the North-east and Yorkshire (clue: lots of local authority action required).

Beyond current sustainable design

For Material Cultures, many mainstream sustainable construction solutions are seen as insufficient. For example, they argue that Passivhaus is problematic because the standard does not account for embodied carbon, and certification is prohibitively expensive.

The Material Cultures approach advocates building with local, renewable materials, plant-based whenever possible

Mass timber products, they explain in Material Reform, “require astonishing volumes of timber to make a building, even without oversizing to slow fire. This means their use makes little sense in relation to actual supplies of timber. [Also,] buildings made from mass timber will need to last significantly longer than the current lifespan of a new-build to make sense from a carbon perspective.”

Additionally, they state that “these systems require the use of glues, preservatives and acetylising chemicals, which are a by-product of the petrochemical industry, produced using energy-intensive and polluting processes”.

Beyond whole-life carbon

The Material Cultures perspective centres around whole-life embodied carbon, but goes further still, to consider a range of other factors in the way construction materials are both sourced and disposed of at the end of a building’s life. To this end, they have developed a “material matrix”, a holistic, open-source tool that can be used to capture a broader range of the socio-economic and environmental benefits and harms generated by individual materials over their lifespan.

In its current iteration, it includes embodied carbon, cost and distance travelled to the point of use. An example can be seen in a report on their work in Birmingham for Civic Square’s Neighbourhood Public Square in Port Loop.

Regenerative construction

The Material Cultures approach advocates building with local, renewable materials, plant-based whenever possible. It focuses on finding ways to combine these carbon-capturing bio-based materials – such as straw, hemp, reed and timber – plus some minimally processed minerals, with modern methods of construction, to create innovative and replicable new ways of building for a post-carbon future.

These new (or rediscovered) materials, and innovative ways of working with them, constitute what they term “regenerative construction”, so-called because it aims not just to do no harm but to actively improve the environment and human wellbeing.

Material Cultures advocates for several key changes to support a shift towards regenerative construction. They propose new grading systems and construction techniques to make better use of shorter and non-standard UK timber, alongside further standardisation of stone blocks to improve their potential for reuse.

Rather than the prevailing cycle of demolition and rebuilding, they argue for a return to a culture of ongoing maintenance and repair. They also call for greater use of unfired clay and increased adoption of factory-based modern methods of construction, which they see as offering the potential for safer and more inclusive working conditions.

Design philosophy

The team at Material Cultures has little time for the tail end of international modernism, instead favouring “critical regionalism”, a concept most closely associated with Kenneth Frampton and his highly influential 1983 article Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.

Frampton positioned critical regionalism as a way to resist both the homogenising tendencies of global modernism and the superficial historicism of postmodernism. Instead, he argued for an architecture that engages with topography, climate and materiality, prioritising tectonic and tactile qualities over purely aesthetic concerns.

Material Cultures’ work follows this thinking, advocating for regenerative construction that uses local, minimally processed materials to respond to specific environmental and cultural conditions. Their approach is less a return to vernacular building and more an attempt to develop contemporary construction methods that remain rooted in place.

Putting theory into practice

A key question remains: to what extent are these ideas practical, and how do they take shape in real-world applications? Material Cultures’ approach, while rooted in research and experimentation, is continually tested and refined through an expanding body of work.

From demonstrator schemes exploring bio-based construction methods to private commissions, community-led developments and ongoing research projects, their portfilio is building an increasingly clear picture of how these principles can be applied – and whether they have the potential to scale up across the industry.

Testing ideas

Quochag steading, Bute

On the Scottish island of Bute, the practice has been commissioned to bring new life to a ruined steading. The new interiors will feature clay plaster, local timber and well-worn stone, with hemp batt and wood-fibre insulation.

Aluminium sheeting is the chosen metal sheet because it can be recycled with no loss of quality. Massoud explains that it has proved challenging to find somewhere local to cut the timber.

“It has also been really interesting to think where we can get clay to plaster the walls close to the site,” he says. “And, when it comes to the mortar to repair the stone walls, traditionally they would have used shells from the seashore.

“Thinking about how that works in terms of sustainability in today’s thinking is interesting.”

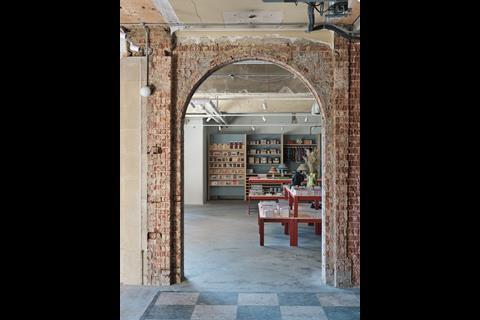

Port Loop

At the Civic Square Neighbourhood Public Square project in Ladywood, Birmingham, Material Cultures is advising on the retrofit of a former council salvage depot into a new community hub focused on sustainability and local production. The 1932 art deco concrete structure, originally designed as a refuse collection depot, is intended to become the site of Civic Square’s Neighbourhood Microfactory + Materials Lab, serving as a community hub and a centre for bio-based material production, skills training and small-scale construction.

The initiative builds on research conducted by Material Cultures in 2024, which mapped eco-responsible building materials produced in the West Midlands – including sources such as sawmills, stone quarries and timber reclamation yards.

INBUILT

As part of its wider research into regenerative construction, the practice is contributing to INBUILT, an EU-funded initiative aimed at advancing locally sourced and reused sustainable building systems to demonstrator stage. The Europe-wide scheme focuses on developing and testing materials that reduce environmental impact while supporting circular construction practices.

Materials involved include rammed earth blocks, recycled and unfired bricks, straw-clay boards, recycled concrete, prefabricated waste-wood wall elements, and bio-based prefabricated curtain walls. The project also explores smart windows with recycled glass and bio-PUR frames, recycled waste-paper and textile-fibre insulation mats, bio-based insulation panels, and second-life photovoltaic panels.

Hemp farmhouse

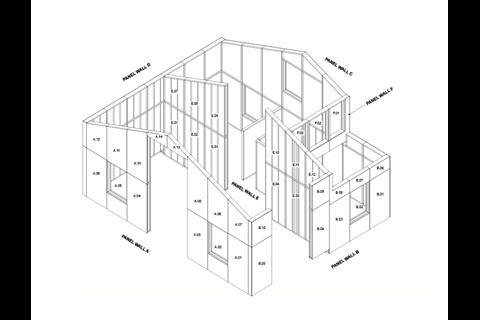

One of Material Culture’s most interesting projects to date is Flat House, at Margent hemp farm near Cambridgeshire – owned by music-video director, Steve Barron – which was constructed primarily from hemp grown on the farm. Hemp straw was mixed with lime and cast into timber cassettes to form the walls.

Meanwhile, hemp fibres were needle-punched into mats, which were then impregnated with a bio-resin – made from waste corn cob, oat hulls and Bagasse (sugarcane waste fibre) – and subsequently heat-pressed into corrugated sheets that were used to clad the exterior of the house, in an agricultural style that has become part of the practice’s trademark aesthetic.

Designed with the aim of prototyping prefabricated sustainable hemp construction, the three-bedroom off-grid house is powered by solar, wind and a biomass boiler. The corrugated hemp fibre board used is available from Margent Form.

Plant-based retrofits

Another strong strand of the firm’s work is retrofits using bio-based materials. They have developed a palette of plant-based materials that has been applied to projects such as the Charleston gallery in Lewes, a former council office, and the Fishtank workshop in King’s Cross.

For the gallery project, the retrofit approach exposes the building’s underlying structure, highlighting its raw materiality while incorporating contrasting elements of bold colour. This approach emphasises the interplay between existing and new interventions, demonstrating how bio-based materials can be integrated into adaptive reuse projects without erasing the historic fabric.

Phoenix development

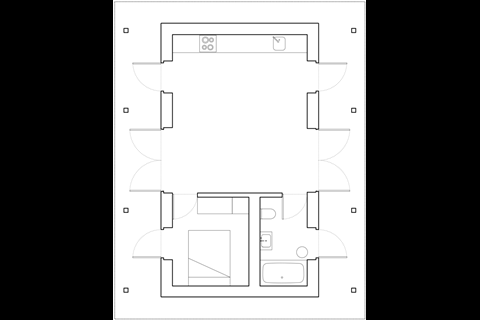

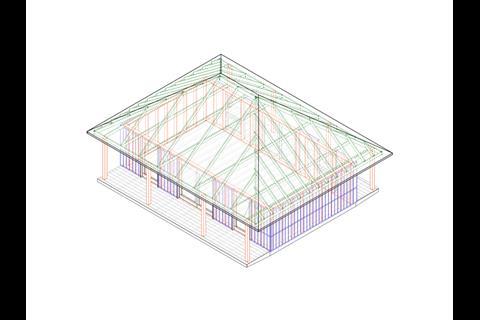

A key question surrounding Material Cultures’ work is its scalability – something the practice is now set to test as one of the architects working on Human Nature Places’ Phoenix development in Lewes. The practice’s contribution includes 150 homes constructed from prefabricated timber cassettes, which will be filled on-site with an insulative hemp and lime mixture.

Massoud acknowledges the challenges of scaling up bio-based construction and the need for early coordination with suppliers. “We’re looking at how we can work with local supply chains, such as local sawmills, to try and scale up to meet the needs of the project,” he says.

For Material Cultures, this approach goes beyond material sourcing to consider the wider infrastructure needed to support regenerative construction. “It’s about thinking in a bioregional way and considering the infrastructure needed to support that approach,” Massoud continues.

“A critical part of the design process is engaging – years in advance – with the people who will provide the materials, ensuring supply chains are ready when you need them.”

>> Also read: The Phoenix, Lewes: ‘This is how we will have to build in the future’

This project will serve as a test case for whether regenerative construction can operate at a larger scale while remaining economically and logistically viable.

V&A bark prototypes

One thing Materials Cultures could never be accused of is being boring. This is a practice with a lot going on. Another strand of work sees the results of recent experiments with tree bark, titled Woodland Goods, on show in the furniture gallery at the V&A until the end of October 2025.

These are beautiful sheet materials created from bark using only natural adhesives and a heat press. Once the natural glues within the silver birch and coast redwood bark are activated, the material binds to itself to form a solid sheet – no toxic glues required.

Massoud explains that the prototypes are not intended as finalised products but as a starting point for further exploration. “By no means are any of the things on display fully resolved. They’re a provocation; an invitation to think in another way,” he says.

“We want people to consider what is extracted from woodlands and considered waste, and how we can make better use of that.”

Education and skills

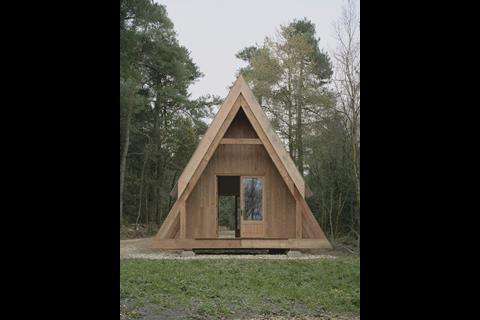

Material Cultures not only applies its research in practice but also integrates it into education, leading the regenerative construction unit on the Master of Architecture course at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. As part of this programme, the team has developed Clearfell House, a demonstrator building that embodies the principles of regenerative construction and low-carbon material innovation.

Education is a key part of Material Cultures’ remit, not only to advance knowledge of bio-based construction but also to address the significant skills gap that threatens its wider adoption. The construction industry already faces a well-documented shortage of skilled labour, with an ageing workforce and a lack of training in traditional building methods.

The challenge is even more acute for regenerative construction, where the skills required – from working with unfired clay and lime to assembling prefabricated bio-based components – are far less common and often absent from mainstream training programmes.

To help bridge this gap, the practice has established a dedicated educational arm called MAKE, which runs workshops in techniques such as clay plaster and lime render, equipping participants with hands-on experience in working with natural materials. However, one-off workshops alone are not enough to meet the scale of demand required for a transition to bio-based construction.

Recognising this, Material Cultures has a longer-term ambition to develop a formal construction curriculum, ensuring that future generations of builders, architects and craftspeople are equipped with the skills necessary to implement regenerative approaches at scale. Without this investment in training, the feasibility of bio-based construction as a mainstream alternative to conventional building methods remains a significant challenge.

Broader vision

Material Cultures’ vision is nothing if not ambitious. The firm wants to see regenerative construction established as part of a wider system of regenerative land use. This could look like the patchwork “mosaic landscape” they discuss in their recent paper on the topic – a system that integrates diverse land uses, such as forestry, agriculture, and conservation, to create a more ecologically resilient environment.

By varying land cover and function across a site, a mosaic landscape aims to support greater biodiversity, improve soil health and enhance carbon sequestration while allowing for sustainable resource production.

Alternatively, their approach could take the form of silvoarable agroforestry, in which agricultural crops or plants are grown between rows of trees to provide interim income while the trees mature. The key principle across both models is the creation of land-use patterns that regenerate ecosystems, restoring soil health, improving its ability to store carbon, and offering a more balanced relationship between the built and natural environments.

Questions

Translating these ideas into reality presents significant challenges. It remains unclear how such systems could be implemented at scale, how they would function economically, or whether there would be enough people willing and able to take on the labour-intensive work required for these forms of agriculture and forestry.

The physical demands of such work are often overlooked – environmentalists, in particular, can have romantic views about the realities of peasant toil.

Yet, as with much of Material Cultures’ work, the proposals raise important questions that warrant serious consideration. At the very least, they offer a provocation – an invitation to rethink how land is used and how those patterns of use relate to what and how we build.

The paper on mosaic landscapes is one of many available on the Material Cultures website, reflecting the firm’s ongoing collaborations with institutions such as Central Saint Martins and ETH Zurich. These partnerships have helped to develop research that not only critiques the status quo but also explores practical frameworks for integrating regenerative approaches into contemporary construction and land management.

As the daughter of a small farmer, I am sceptical about the economic viability – and even the appeal – of some of Material Cultures’ wider theses about land use. But thought experiments are as important as material experimentation, and I am glad there are young people out there who are busy imagining different ways of doing things.

Barriers to change

Material Cultures is clear about the challenges, particularly in an industry structured around regulation and standardisation. In Material Reform, they note that departing from conventional construction methods means greater accountability for designers and builders, who cannot rely on the usual frameworks of certification and standardised systems.

“Working with non-standard materials sets you outside of most of the infrastructures that support and regulate construction,” they write, adding that this forces practitioners to take on a higher degree of responsibility.

“Those of us making buildings outside mainstream practices cannot outsource responsibility for the performance of a building to manufacturers, systems of standardisation and installation guidelines.”

As a result, they argue, working with alternative materials requires a greater willingness to navigate uncertainty and accept increased risk – something that remains a significant barrier to wider adoption.

Of course, there are other forces militating against change. While commerce, professional reputations and egos remain tied to large-scale, technically complex steel and concrete projects, it can be tough to imagine a future built from such humble and rustic materials as those in the Material Cultures palette.

For those invested in the status quo, a conscious effort may be required to overcome the instinctive recoil. But it is a necessary effort, as Material Cultures may be offering a glimpse into the future of construction.

Where to start?

Even if the future of the built environment follows a more hybrid approach than Material Cultures envisages, the sustainable solutions the firm is developing are likely to play an increasingly significant role in building design.

So, where would Massoud advise building designers who are just beginning to work with plant-based materials to start? He suggests wood wool as an accessible option: “It’s kind of shredded timber, or scraps of wood, mixed with lime or cement to create a board: that’s a good material.”

As the industry grapples with the urgent need to decarbonise, their work presents a compelling case for rethinking the fundamentals of how buildings are made – and what they are made from

Another material he highlights is Strocks, which function similarly to adobe blocks but remain unfired, significantly reducing their carbon footprint. “They both absorb toxins in the air and regulate temperature,” he explains, making them an effective choice for low-carbon construction.

Massoud also points to hemp-based materials, which are already central to Material Cultures’ work. “Hemp blocks and hempcrete are things we tend to use quite often,” he says. He also suggests replacing metal wall studs with timber studs, reinforcing the practice’s commitment to minimising reliance on industrially processed materials.

Then he adds enthusiastically, “We’re working with a fabricator in Germany to develop some boards made from wetland grasses. We’re testing them out in an exhibition at the Wellcome Trust later this year. It’s really exciting.”

Massoud smiles for a second and, beneath the earnestness, you see a flash of the inventor’s delight.

It can take time to adjust to the idea that the cutting edge of construction may not lie in high-tech innovations, but in the rediscovery and reinvention of humble, natural materials – those that have been used in vernacular architecture for centuries. Unfired clay, straw, local timber and other bio-based materials, once dismissed as primitive, are now emerging as some of the most viable solutions for carbon-negative building.

Material Cultures is at the forefront of this shift, demonstrating how these materials can be adapted to contemporary needs without compromising performance or architectural ambition. As the industry grapples with the urgent need to decarbonise, their work presents a compelling case for rethinking the fundamentals of how buildings are made – and what they are made from.

>> Also read: Jan Kattein: architect as catalyst – ‘A transformational impact can be achieved with limited means’

>> Also read: The Phoenix, Lewes: ‘This is how we will have to build in the future’

2 Readers' comments