Paul Rudolph’s visionary architecture helped shape mid-20th-century modernism, yet his work faces an enduring struggle for recognition and preservation. A new book, to accompany a major retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, offers a vital reappraisal, finds Jon Wright

Paul Rudolph’s work has remained dangerously undervalued since his death in 1997, despite his stellar career as a designer and teacher. Wilful destruction has seen the loss of his superb 1972 house in Westport in 2007, the Biggs Residence in Delray, Florida in 2020, and the high-concept Burroughs Wellcome Centre in North Carolina – which met the wrecking ball in 2022 despite a campaign to save it. There have been numerous other unnecessary losses that largely mirror the UK’s own difficulties in protecting post-war buildings. Elsewhere, force majeure has taken over, and the recent destruction of his Sanderling Beach Club in Florida by Hurricane Helena has meant another piece of his oeuvre is lost to us.

That there is a Rudolph-shaped gap in our wider understanding of 20th-century architecture is something of a surprise, as he was a major figure in the 1950s and 60s. He suffered a huge decline in popularity as postmodernism dawned, and history hasn’t been kind to him or his buildings; even Kenneth Frampton’s famous critical account of the period gives no mention of him or his work.

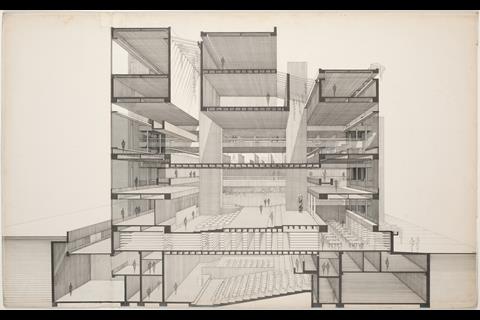

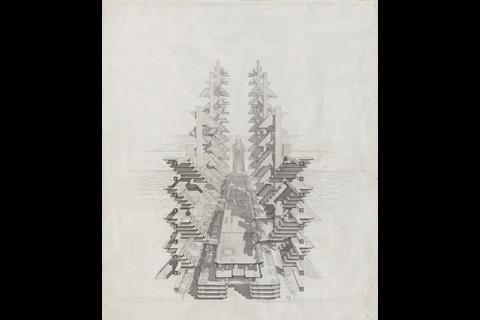

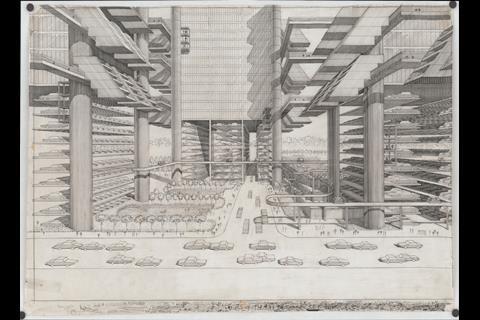

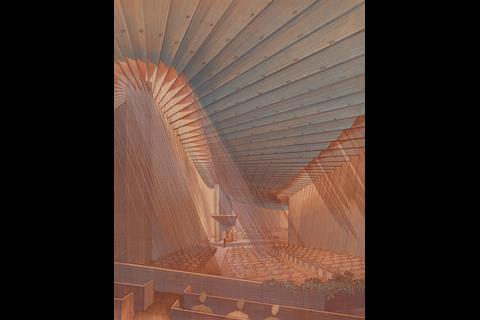

That the Met should choose to focus on Rudolph as the first 20th-century architect to have a retrospective in 50 years (except for the Calatrava drawings exhibition in 2006) is, then, both vital and overdue. This book is a beautiful catalogue of a show that tracks his output through drawings, models, and ephemera, with concise text from Abraham Thomas, the Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts. The epithet ‘lavishly illustrated’ is something of a disservice here because, above all, this is a chance to look at the collected drawings of arguably the most gifted architectural illustrator of the last century. Visions of modernity that stray into the visual language of science fiction, Rudolph’s exquisite line drawings express a stark, clear-cut world of form and order.

Descended from modernism’s first-wave pioneers but tending towards a sculptural monumentality as expressed in the theories of Siegfried Giedion, a contemporary of Pei, Saarinen, and Kahn, Rudolph’s career was reflective of modernism’s second-wave attempts to settle itself and adapt to new socio-political realities. His work is hard to categorise, offering in retrospect what Thomas terms a ‘confounding and self-contradictory set of propositions to consider.’

The book is largely chronological, beginning with his early houses in Florida in the 1940s, many of which were designed with his early mentor Ralph Twitchell, the founder member of the Sarasota Modern movement. Rudolph studied under Gropius at Harvard, who managed to get him out of the Korean War with an impassioned letter and advocated publicly for him as a major talent.

The early houses are masterpieces of invention and sculptural expression in contrasting materials – some using plywood for roof spans for the first time. Their variety of form and materials – contrast the timber and steel-framed Walker Guest House (1952) with the plans for the Knott Residence the previous year – show an architect unfettered by style and more concerned with site, experimentation, and technology. In these things, Rudolph was progressive, and in his highly readable account of the period, Thomas makes sure we see Rudolph as a theorist as much as a designer.

Chapters on Urban Renewal, Civic Campus, and Megastructures make clear the huge leap Rudolph’s career took as the austerity of the immediate post-war period in the US gave way to two decades of urban regeneration and remodelling from 1950 onwards. Sculptural Brutalism was in, and the monumental scale of Rudolph’s schemes, both built and unbuilt, gives an idea of how central he was to the larger post-war development of major US cities.

They hint also at the reasons for his decline. His widely publicised but unbuilt Stafford Harbour project from 1966 illustrates the audacity that lay behind the élan of the renderings. It was an audacity that was to pave the way for the reaction against modernism that was crystallised – rightly or wrongly – by the Pruitt-Igoe demolition in 1976.

The final two essays explain the ‘what happened next’ in Rudolph’s career as commissions slowed to a trickle and he turned back to smaller-scale work, focusing specifically on interiors. Drawings and images of the quite incomparable 23 Beekman apartment are a revelation, as are those of his 1989 masterpiece, the Modulightor Building – both in New York and both rare surviving pieces of his legacy.

So out of focus has that legacy been that concentrating on the architecture, rather than the architect, is understandable; but that is what is missing here. A few anecdotes from students aside, there is little that takes us past the drawing board to give context to what was an extraordinary career. This is an essential book nonetheless and adds significant weight to the continuing battles to protect his surviving works.

Postscript

Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph by Abraham Thomas is published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jon Wright is Twentieth Century Heritage Consultant at Purcell.

No comments yet