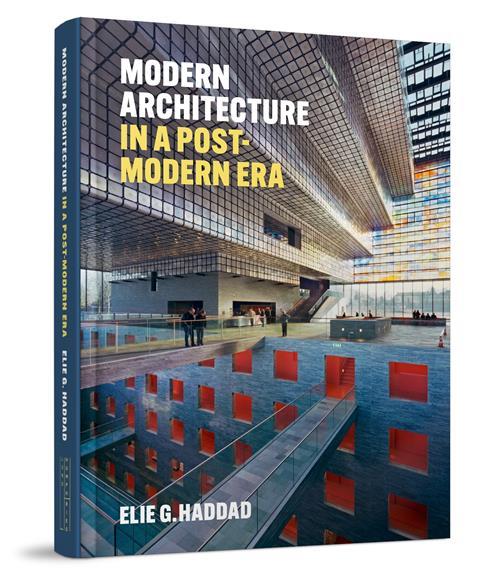

Jon Wright finds Elie G. Haddad’s book to be a succinct exploration of post-war modernism, mapping the evolution of key architectural styles over six decades

For those of us who spend any of our time trying to sift, characterise, or otherwise make sense of the architecture of the recent past, this succinct account of the last six decades is a welcome addition to the spot on the bookcase marked ‘The Big Picture’. What it may lack in context it more than makes up for in the kind of enjoyably broad sweep that makes some of the key works of architectural history such a good read – let’s face it, they aren’t always that. But the key works of Frampton, Giedion, and William Curtis – all of whom attempted to survey the modern period from a distance – are the progenitors of this highly readable account of what happened after modernism, and it’s a decent stab at settling into some kind of position the disparate and worldwide fracturing of the modern project.

The history of modernism has long been an account, on the one hand, of how far back we trace its beginnings and, on the other, what the reactions of discontented architects were in the post-war period. As much as enquiries into the chief exponents of the international style of the interwar period, these two areas have drawn considerable academic attention, and this book takes the logical next step and tries to answer what happened to the discontents and those architects who followed them.

After addressing the discontents through an engaging essay on the work of Bruno Zevi, Van Eyck, and Christopher Alexander (whose pavilion at West Dean College I’ve always admired), we get a style-by-style rundown of the branches of post-war modernism and where they have led us. The groundings in each of the ‘styles’ are passable but lack a richness of context that will leave some readers reaching for other, more detailed accounts. From time to time, Haddad points the way to these other texts, but not in every case. So, we get brutalism, neo-rationalism, high tech, and pomo first, with each described through key works and chief exponents. For brutalism, I was forced to let slide an early and frankly lazy assumption that Robin Hood Gardens was a failure, ‘despite all its good intentions’, but these are elsewhere solid histories with few fresh takes.

![Seashore [4]](https://d3rcx32iafnn0o.cloudfront.net/Pictures/480xany/4/2/4/1992424_seashore4_228147.jpg)

The real purpose and joy of this book is to be found in the end sections of each style, where Haddad unveils the later developments of each of these departures and gives well-illustrated examples from a global perspective. There is revelation to be found in the latest examples of brutalism and neo-rationalism, Vector’s Seashore Library in Beidaihe New District in China being an example of the former. The geographical splits make straightforward comparative critique easy and underline the very earliest of modernism’s aims – that architectures should be global and transferable. That Haddad’s categories are all, indeed, international styles borne out of modernism’s second and most successful flowering (whatever failures one might retrospectively decide on) is the foremost significance of this work. It’s going to be a useful starting point for future heritage protection, and it marks out clearly, through comparative analysis, what we should be valuing from the last few decades in the future. With a book so vast in scope that balances theory and project, ideology and aesthetic, that’s perhaps the best Haddad could have hoped for.

Postscript

Modern Architecture in a Post-Modern Era by Elie G. Haddad is published by Lund Humphries.

Jon Wright is Twentieth Century Heritage Consultant at Purcell.

No comments yet