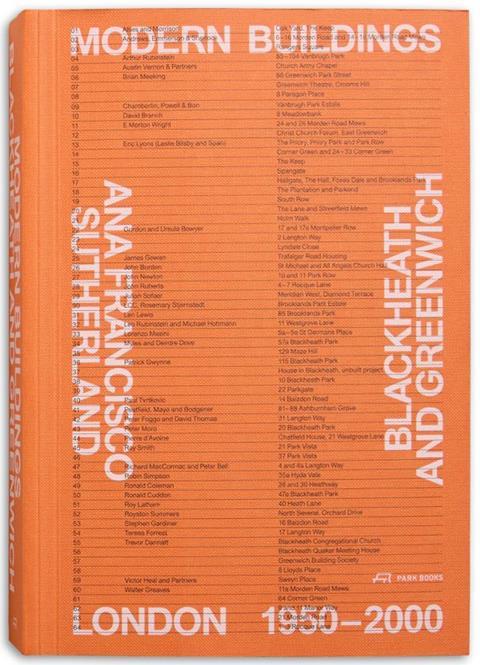

Ana Francisco Sutherland’s new book demonstrates compellingly how the architecture that now characterises the area is deeply rooted in the place and its history, writes Nicholas de Klerk

I should declare an interest at the outset of this review; I have lived in the subject area of Ana Francisco Sutherland’s new book for almost a decade and for almost four of them in one of the buildings she has included in her study. Francisco Sutherland herself has lived in the area longer than I have and lives in another of the buildings. Meeting her to discuss the book, she explained how it started as a research project alongside starting her own practice which took on a new impetus during the pandemic in 2020.

This decade-long project is personal. In it, Francisco Sutherland has compiled building profiles, interviews with the architects and their families as well as their clients. As Neil Bingham points out in his introduction Francisco Sutherland has taken advantage of the fact that the construction of many of the buildings and the lives of their designers and occupants are within living memory. She has documented a compelling oral history of her subject(s) and has ‘woven a story of relationships.’

This demonstrates just how personally invested the architects and their clients were in these projects, and further shows the astonishing concentration of groundbreaking and in some cases radical modernist projects in the area. The work of Eric Lyons with his client Leslie Bilsby on Span housing projects is relatively well known but other names that populate this pantheon include familiar ones such as Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, Walter Greaves, Peter Moro, Trevor Dannatt, James Gowan and Patrick Gwynne as well as perhaps less well-known names such as Julian Sofaer, Leo Rubenstein and Royston Summers.

Half of the photographs of the architects in the book have been sourced from the RIBA archive and half, never seen before, from personal archives. Completing the photography of the buildings that survive was a two-year undertaking by Pierce Scourfield. Francisco Sutherland notes in the introduction that she has taken the opportunity to provide more information on less well-known architects than their better-known and published counterparts (all gathered through primary research) and as such has made a valuable contribution to the body of knowledge on this period of architecture and in this area.

Francisco Sutherland has designed a fascinating graphic which charts the relationships between the various architects featured in the book, as people who were friends, had worked for or with one another, as teacher and student, people who have designed their own houses or who have lived on a Span estate. This mapping places Dannatt, Greaves, Moro and Gordon and Ursula Bowyer at the heart of this community – for, in this telling, it certainly appears as one.

It also, at a glance, shows how few women were identified as authors of buildings in the area – and who make up only two of this number – which tells a slightly different story. This, as is so often the case, is a function of how these histories are written. Here too, Francisco Sutherland makes an important contribution in surfacing other stories and designers such as Rosemary Stjernstedt, Carol Moller and Teresa Forrest, that might otherwise remain less visible.

Francisco Sutherland posits the book as one about relationships, and there are many stories about individual architects and clients that illustrate this. This is sketched out against a backdrop of life in post-war London, with details of areas within the two neighbourhoods that suffered significant bomb damage and the planning and policy response across the capital that considered the question of rebuilding not just housing, but places and communities after the war. Material shortages also shaped how early Span housing was designed, with painted timber cladding and wall tiles replacing the use of brick.

The 1951 Festival of Britain also played a part with the restoration of the Paragon, recognised as one of nineteen projects that ‘contributed to civic or landscape design’, while a significant number of architects working on Festival projects lived or worked in the neighbourhood. This all took place in the context of an area rich in both heritage and architectural experimentation which are, the book suggests, fundamental to both the concentration and the design of the modernism that followed.

To see Modern Buildings in Blackheath and Greenwich as simply a guide to buildings of a defined period in a specific area would be to miss the point of the book, in my view. It reads more as a genealogy and demonstrates compellingly how the architecture that now characterises the area is deeply rooted in the place and its history. The lives and stories of the architects and their buildings, of the people who lived and continue to live in them, whose influence spread far beyond the confines of this study, makes the case for its wider relevance and, I think, as a template for similar studies of other parts of London.

>> Also read: Londoners Making London: ‘There is a gap in physical space that creative, determined people fill’

Postscript

Modern Buildings in Blackheath and Greenwich: London 1950-2000 by Ana Francisco Sutherland, is published by Park Books

Nicholas de Klerk is an architect and associate partner at Purcell

No comments yet