Ben Tosland reviews the 70th-anniversary reissue of Outrage, Ian Nairn’s seminal critique of Britain’s built environment, exploring its lasting relevance. Gareth Gardner provides contemporary images that capture twenty-first-century subtopia

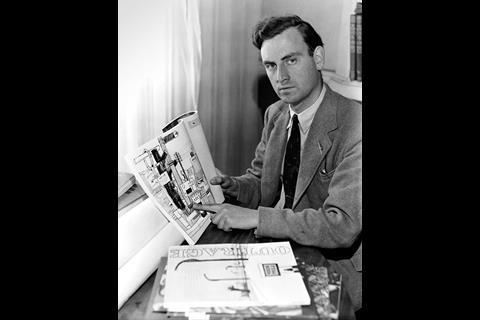

Aged 23, Ian Nairn became an assistant production editor at The Architectural Review. He was angry about the condition of the built environment in Britain and the sprawl of cities eating into the confines of the countryside. This anger translated into an entire ‘incendiary’ issue of The Review, titled Outrage, published in 1955 under the editorship of Hubert de Cronin Hastings, also owner of the Architectural Press. Re-released in February 2025 by Notting Hill Editions for its 70th anniversary, it is complete with an erudite introduction by the cultural commentator Travis Elborough.

Outrage is best known for its ‘Route Map’ section, with each page representing ‘strides of 25 miles’ between Southampton and Carlisle. The aim was to ‘present a typical cross-section of the country – of the countryside’, and it was complete with Gordon Cullen’s illustrations and Nairn’s own photographs, taken with the Architectural Press’s office Leica camera. The point Nairn made was that of liminality. For Nairn, visual planning was about definition between places. But the edge of the town had become rusticated, while the countryside had become suburban. These places between places were now subtopian – Nairn’s own portmanteau – and lacked genius loci.

His biography is well known. He had studied maths at university and later became an RAF pilot officer, serving in the skies above East Anglia, from where he had uninterrupted views of the country’s network of fields, villages and towns. While stationed in Norfolk, he wrote architectural articles for the Eastern Daily Press. Here, he honed his mastery of the English language, often noted by those who have written biographies of this oddity of architectural criticism.

The sad story of his later life is well known too. Described by Owen Hatherley as ‘gawky and fat’, such descriptions are often coupled with tales of a dozen pints of beer a day in the St George’s Tavern, a ‘fag-ash’ Pimlico pub close to his flat. Days of filming were cut short for Nairn Across Britain so that he could hurry to the nearest boozer before driving on to the next town. Melancholy and despair cut his life short. ‘Unfulfilled potential’, as Elborough remarks.

Famously, Nairn worked with Nikolaus Pevsner on The Buildings of England volumes for his home county of Surrey and then for Sussex. Pevsner used the caption of Nairn’s portrait on the dust jacket of the Sussex edition to, almost diplomatically (you feel he tried), summarise their working relationship by stating: “He found the journeys for The Buildings of England immensely interesting and rewarding, the mountain of correspondence and detailed checking that must follow them rather less so. Of his other books, Nairn’s London and Nairn’s Paris, written for Penguins [sic], embody a more personal and less correct view of architecture than was possible within the framework of The Buildings of England.”

Elborough’s introductory observations tie Nairn into a context of landscape and Englishness. He shows that Nairn was not out of sync with contemporary authors such as Nan Fairbrother and Richard Mabey and that he was a contrast to architecturally trained critics such as Reyner Banham, Colin Rowe or Hugh Casson. For contemporary context, W. G. Hoskins had just published The Making of the English Landscape (1954), and there was a general sect of society that was nostalgic for the landscapes, towns and cities of pre-war Europe. In a Venn diagram of the architectural establishment – in which he did not quite fit – and landscape historians, Nairn is the crossover.

Nairn’s ‘less correct’ opinions, usually focused on subjective visual planning, caused division by disparaging planners and architects alike. In republishing Nairn’s work, there is an implication that his writing remains relevant. Those in the architectural profession might question whether he was ever relevant. In Outrage, Nairn asserted that greater density in city centres would ensure the countryside’s survival. He predicated this on the presumption planners had made that England was of an ‘unlimited size’. And while he was concerned with the romance of old England, such strategic thinking is not out of place in a society today grappling with the climate crisis.

In Outrage, specifically in a section on Anti-Urbanism, he stated: “The leaders of planning – a long way up from the insides of the local offices that reject modern houses as being out of tone with the amenities of the (speculative semi-det) district – recognise the futility of it, but they have backed the wrong horse; decrying increased urban densities in the heart of the town, when that is the only thing likely to save us, and proposing new and expanded towns when the UK is so small that they will very soon run together.”

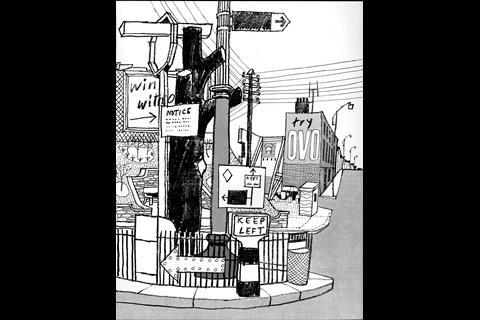

His comment on the smallness of the United Kingdom recalls Nairn, in his cockpit, fulminating at the sprawl below. And on the ground, his almost (at times) petty critique expanded to the muddle of street furniture, cluttered vestiges of former military bases, and the ubiquity of the suburbs and semi-dets that ran out of London on the Edgware Road, making the end of Southampton share the appearance of the beginning of Carlisle.

The gawky, contradictory Ian Nairn, a spectre in an ill-fitting suit, continues to lurk in the background of culture and the built environment today. Subtopia, for Nairn, was a tainted middle ground – neither urban nor rural. The anger with which this notion was presented has influenced polemical cultural commentators since, including Jonathan Meades and Owen Hatherley; Nairn has also been compared to the late Gavin Stamp.

The premise of subtopia continues to influence others. Iain Sinclair has trekked the route of the M25, rummaging through London’s edgelands, while the photographer Gareth Gardner continues his long-standing interest and is about to set off to chronicle the outer reaches of Southampton and Carlisle with his camera. As for the built environment, Nairn’s critique was not ecological, but the distinction between the urban and rural remains relevant in today’s arguments for sustainable, location-driven development.

>> Also read: Review | Modern Buildings in London by Ian Nairn

Postscript

Outrage by Ian Nairn first published in 1955, reprinted with an introduction by Travis Elborough by Notting Hill Editions in 2025.

Ben Tosland is an Associate at Montagu Evans in the Historic Environment and Townscape team. He is a part-time lecturer at New York University (London). His book Who Are Godwin and Hopwood? was published in 2024 by Birkhäuser.

Architectural photographer, gallerist, and writer Gareth Gardner (a former BD journalist) has illustrated this review with his photographs from his 2015 project Route Book. He retraced Nairn’s journey from Southampton to Carlisle, photographing roundabouts, derelict pubs, out-of-town shopping centres, suburban houses, and fake trees, among many other things. This year, Gareth is set to continue his Nairn-inspired work by documenting the edges of Southampton and Carlisle for his next project, The End Will Be Like the Beginning. His gallery in Deptford is dedicated to photography of architecture and place.

1 Readers' comment