Kudzai Matsvai reviews a ‘powerful new resource’ that explores the reasons behind dysfunctional workplace practices in architecture and suggests new ways to move forward

When the revolutionary five-day workweek was popularised by Henry T. Ford almost a century ago, it was seen as a significant win for the working masses. However, the model did not account for factors such as race, gender, disability, or social class in shaping the notion of a work-life balance. Thus, the eight-hours-a-day, five-days-a-week working model was created based on the time that the average white, heterosexual, cis-gendered, able-bodied, white-collar working man in the West could afford to commit to work.

This man had all his domestic tasks taken care of by a partner who often simultaneously played the roles of full-time parent, in-house chef, maid, launderer, gardener, and every other role required to keep the average nuclear household afloat, leaving him ample time to commute, work, and even enjoy leisure activities and downtime. Since its inception, we have failed to evaluate whether this model remains suitable for workforces that are becoming more diverse and, therefore, more complex.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic was generally a negative experience for most people globally, it did create an opportunity for us to question many long-held conventions. One of the fallacies we began to interrogate was the illusion of a healthy work-life balance in the modern professional world. This was particularly true for the architectural profession, where time commitments often far exceed those of other occupations, greatly impacting people’s personal lives and mental well-being.

It is safe to say that pretty much everyone moving through the profession has had their personal lives negatively affected by both education and practice. We have all had to cancel plans, work late, and even give up weekends to meet the ever-growing demands of the architectural world. However, during the pandemic, the financially, mentally, and physically taxing nature of expectations such as going into the office five days a week was brought to the fore, and the post-pandemic attempt to reinstate those “norms” forced us to confront the reality that the aforementioned working model was no longer fit for purpose.

While we are now aware that there is a problem, what to do about it is far less clear. The demands of the profession are indeed growing, especially given increased global competition and economic strain, so how do we begin to tip the scales back towards balance?

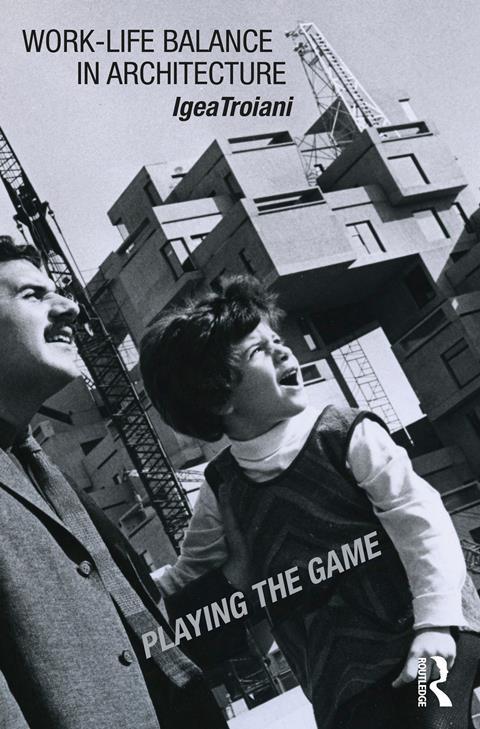

As we continue to grapple with these pressing and pertinent questions, we must recognise that although we do not have all the answers, we do have crucial resources like Playing the Game: Work-Life Balance in Architecture to guide us.

At the core of this book is the simple idea that people who feel better will ultimately do better. In exploring this concept, Professor Igea Troiani recognises that increasingly diverse demographics are entering the architectural profession, and she takes an intersectional approach to understanding their differing well-being needs. Acknowledging that work-life balance looks different for everyone, she explores how best to accommodate the needs of those who “do not fit, or want to replicate, the traditional ‘24/7 white, male architect lifestyle.’”

Igea urges us to evaluate where we are and offers practical, actionable ways to move forward

The book also possesses a candour so desperately needed given the current state of the profession, going so far as to suggest that perhaps a career “not in architecture at all” may be what many need for the sake of self-preservation. I would recommend it as essential reading for anyone considering pursuing a career in architecture or anyone currently questioning their place in the profession, as it plainly lays out the good, the bad, and the ugly realities.

For example, Igea explores the very real yet still taboo “impact of a corporate, neoliberal ‘big business’ approach” on how the profession operates and the resultant toll this has taken on people’s well-being. If you ask most people in the profession what makes the job difficult, they will likely corroborate Igea’s list, which includes ongoing challenges such as moving through an architectural education, poor professional remuneration, taxing work environments, and high competition.

In recent years, taboos surrounding mental health have been broken, and many now recognise the importance of not only understanding but prioritising one’s mental well-being. However, this book recognises that, although these conversations are now prevalent, very rarely are these concerns translated into action. In other words, as a profession, we are talking the talk but failing to walk the walk.

Igea also highlights the fact that many harmful workplace practices are extensions of poor behaviours nurtured in educational environments, as more and more, architectural education is being recognised as detrimental to people’s well-being.

>> Also read: Bartlett report sheds much-needed light on our profession’s wider failings

I would also recommend this book to anyone simply curious to know more about where the industry is and how it got here, as it provides great background on the effects of neoliberalism and helps us to understand how this dominant ideology is impacting our profession. Igea suggests that neoliberalism is largely to blame for the role of the architect as it exists today, arguing that it has greatly altered the way the profession operates and shifted the role of the architect away from “former modes of privileged, leisurely, autonomous, artistic, self-oriented, and site-responsive practice.”

She also argues that under neoliberalism, the role of the architect has been transformed without the architect having any control, which has greatly impacted the way we navigate the profession. Essentially, there is a disconnect between what people think the profession is and what it has become, and our institutions of higher education fail not only to address this but also to articulate it to prospective architects.

Igea also explores interesting emerging discourse, such as how our increasingly digitised and connected world has led to many modern workers being unable to separate personal and professional life because they always have work at their fingertips.

I urge all architectural practices and schools that have voiced a desire to advance inclusive agendas to read this book from cover to cover because it highlights a key point that most are still failing to address successfully: diversifying your cohorts and staff requires diversifying understanding, policies, and the ways we work and learn.

Although it may seem like this book is purely about pointing out where we have gone wrong, I would argue that it is a guide. Igea urges us to evaluate where we are and offers practical, actionable ways to move forward, but she recognises that it is impossible to do so without first understanding and acknowledging why and how we got here.

In the words of Albert Einstein, “Learn from yesterday. Live for today. Hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.” Igea has created a powerful resource that allows us not only to learn and question but, more importantly, to dare to live and start to hope.

This book is a timely reminder to reject the capitalist imposition that requires us to measure our worth by metrics of productivity and career progression. It reminds us that sometimes the most daring act of resistance is to simply exist, and that we can begin resisting by reclaiming the ‘life’ in the work-life balance.

>> Also read: Architect: The evolving story of a profession

>> Also read: Inclusion Emergency: ‘An emergency that we can no longer afford to ignore’

Postscript

Playing the Game: Work-Life Balance in Architecture by Igea Troiani is published by Routledge

No comments yet