How do you recreate the work of a genius out of nothing but rubble? And even if you can, how do you keep a construction project that was started in the 19th century from going off the rails? Daniel Gayne went to Barcelona to find out

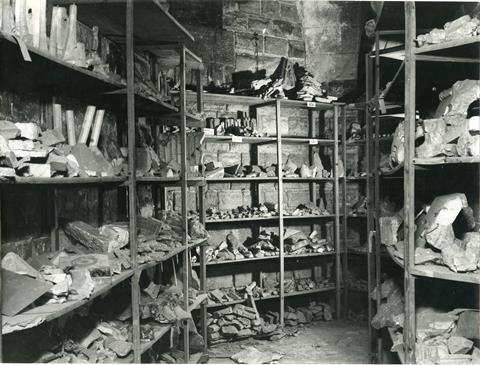

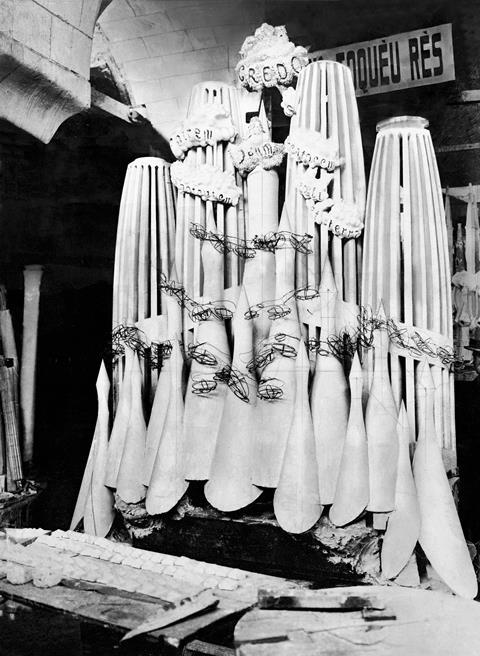

Little was left in the workshops but shattered plaster.

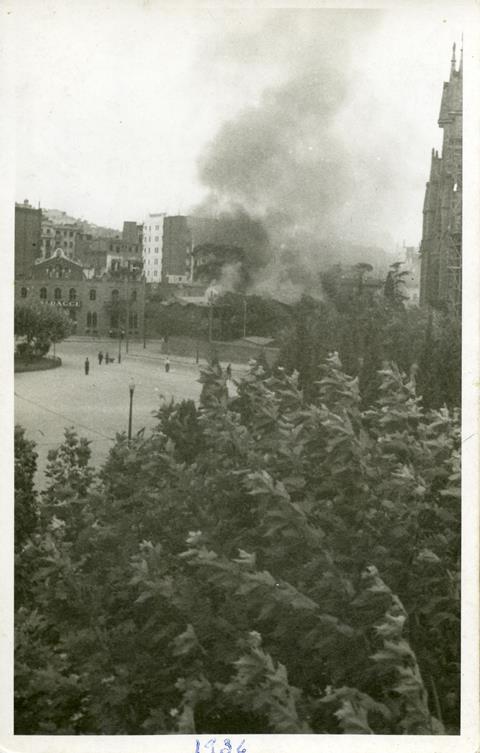

It was the summer of 1936 and Catalonia was alight with revolutionary fervour. After a failed coup d’etat against the left-wing Republican government, Spain had fallen into civil war and Barcelona into the hands of the anarchists.

Across the city, churches were targeted as decades of accumulated resentment against clerical authoritarianism was unleashed - and the revolutionaries made no exception for the strange, half-finished church on the north-eastern edge of town, the final masterpiece of an architect once revered in Barcelona.

Antoni Gaudí had been dead for more than a decade but his disciples were carefully carrying out his vision based on the many models and drawings he had left, and it was these that the radicals targeted.

On 20 July, members of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) came to the Sagrada Família and destroyed what they could. Drawings, photographs and letters were burnt, models were smashed, stones blocks destroyed, machinery vandalised and site buildings razed to the ground.

The militants returned later that day to dynamite the one facade that had been built already, but either failed or were talked down. Instead, they slung a banner between its two towers, advertising the Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth.

And there it stood from that day on, the ruin of a dream already half a century old – the secrets of its design lost in a mess of plaster and acrid smoke.

Stranger in a strange land

That was the truth - as far as anyone in Britain cared to know it - for several decades, Mark Burry tells me as we wait patiently for our waiter to take our drinks order.

Down the road at the Estadi Olímpic, Barcelona are playing PSG in the Champions League, and the sounds spilling out of the cafe-bar we have made our perch for the evening tell us that some things are more important than serving Anglos beer.

It is late afternoon in mid-Spring, evening drawing in, and the long shadows cast over our meeting spot speak for themselves as a repudiation of those who once sought to bury the Sagrada.

Today, the Basílica i Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família, to give it its full name, is one of the most recognised and most visited religious buildings on the planet. It is easily the most popular pick when Building asks contributors to our long-running “Five minutes with” column to name their favourite building in the world.

In 2026, the Sagrada will top out and become the tallest church in the world, with its central spire rising to 170 metres, just shy of the nearby Montjuïc. I’ve come to Barcelona to meet some of the men who helped get the Sagrada to this point; the latest in a long line of architects who laboured selflessly to drag another man’s dream out from the rubble and make it matter.

Burry is one of them, and I’m told he has an extraordinary story to tell.

These days, New Zealand-born Burry works at Swinburne University of Technology’s Smart Cities Research Institute, and like so many other architecture professors today, he could talk about the Sagrada until the sun sank. But when he began his architectural education at the University of Cambridge in the 1970s, Gaudi was a profoundly marginalised figure. “We were introduced to Gaudí in about two sentences with a picture of the abandoned building,” he tells me.

The war in Spain had ended with the victory of a fascist leader who would long outlast the Second World War and the country spent these decades relatively closed off from the rest of Europe. The Sagrada, it was believed in the UK, was a lost project, and Gaudí a brilliant but dismissible maverick.

“That was what was implied,” Burry continues. “We needed to be aware that there was this unique individual and he may have been a genius but that there was no school. “But I’m from the Antipodes and a red light for us is a green light.”

In 1979, Burry persuaded the university to give him a grant for a short trip to Barcelona to research Gaudí, but it was only once he arrived that a local professor revealed an astonishing fact – the project was still ongoing. The academic generously offered to introduce Burry to the two architects still working on the project. “You can imagine my surprise when I found myself with two 90-year-olds,” says Burry.

It transpired that the project had been kept alive by Gaudí’s disciples, who had spent the years after the civil war scraping together what was left behind by the anarchists.

After the 1938 death of Gaudí’s heartbroken protégé Domènec Sugrañes i Gras, who had overseen the completion of the Nativity facade after his master’s death, leadership of the project was taken up by Francesc de Paula Quintana, who had worked under Gaudí and Sugrañes since qualifying as an architect in 1918.

Actual work on the project slowed to a halt in the 1940s, with energy focused instead on restoration and research. But, in 1954, work began on the deep foundations of the Passion facade and the first free-standing column for the interior was put in place in 1957.

By 1966, Quintana was dead too, with his two associates Isidre Puig Boada and Lluís Bonet i Gari left as co-directors.

This was the pair of nonagenarians to whom Mark Burry was introduced in 1979. “They knew Gaudí when they were young architects,” he explains.

“They used to rock up in the last years for lectures on his latest discoveries on site where he was living, and in return they would go out and try and raise money for the project.”

A strong heritage, then, but Burry wondered nonetheless whether this gave them the authority to continue Gaudí’s work without models or plans to guide them – a question he put to the pair.

He was not the first to have raised the issue. In 1965, a collection of architects and intellectuals including heavyweights such as Joan Miro, Alvar Aalto and Le Corbusier, wrote an open letter stating their opposition to continuing work on the church.

By way of an answer, the two architects pointed Burry to a room full of smashed up plaster of Paris fragments, before explaining that Gaudí’s designs were routed in fundamental geometric forms, meaning the church had an underlying grammar from which its design - in theory - could be recreated.

The Passion facade had been relatively simple, being a parametric variant of the one built by Gaudí himself. But now, faced with the task of building the rest of the church, they had reached something of an impasse.

The two men told Burry: “You have arrived at the exact moment that we are asking these questions ourselves. We know he has these geometries, we don’t know how to translate them.” Then, to his surprise, they asked the curious young architect if he wanted to help.

From sculptor of buildings to architect

The Sagrada Família was always meant to be someone else’s masterpiece. The passion project of pious Barcelona bookseller Josep María Bocabella i Verdaguer, the first stone of the church was laid on 19 March 1882.

Bocabella had initially appointed the official diocesan architect Francisco de Paula del Villar to design a church on the scrubland set aside for horse racing in the village of Sant Martí de Provençals just outside the city limits. But del Villar was dismissed after falling out with his client.

He asked another architect, Juan Martorell, to take over, but having advised Bocabella on del Villar’s dismissal, Martorell felt uncomfortable taking over the post. Instead, he recommended his protégé Gaudí , who, legend has it, had a shocking resemblance to a blue-eyed, ginger-haired knight that had appeared to Bocabella in a dream.

Taking over in 1883, Gaudí immediately began developing del Villar’s neo-gothic designs and impressed his client by quickly completing the crypt, before moving on to the first facade, which he wanted to complete before any other parts of the building as a demonstation of intent which would make the project more difficult to abandon. Through the early years of the century, Gaudí made progress on the facade, utilising techniques which ranged from cutting edge (the use of photography to work out how statutes should be twisted and warped in order to look right at height) to the bizarre (his decision to cast live animals in plaster, at one point having to chloroform a particularly obstinate donkey).

The church survived a week of anti-clerical violence in 1909, but the architectural styles that Gaudí and his peers had pioneered were beginning to fall out of fashion, and the following year a bout of brucellosis brought him close to death’s door.

Burry believes that these years marked a change in Gaudí which would be crucial to his and his colleagues’ ability to later revive the architect’s vision for the Sagrada. “My argument is that he transitioned from being a sculptor, doing sculptures of a building proportion, to being an architect,” he says.

“That meant that he could move from being an idiosyncratic agent for every single action required to get a plastic artistic expression, to working in a team and translating an idea into an artefact.

“I just imagine him convalescing for months, looking at the ceiling and thinking ‘what am I going to do’. And that’s what he did, he found a way to direct the project afterwards.”

For the last decade of his life, Gaudí would devote all his attention to the Sagrada Família and to creating a grammar of design to pass on to the next generation, an architectural code that would keep Burry busy for the better part of 40 years.

Cracking the Gaudí code

At first, though, Burry was less than convinced. Back in England, his mates were heading off to work for the Eric Lyons and Norman Fosters of the world. Choosing between the cutting edge of high-tech architecture and the passion project of two hoary Catholics seemed simple. But, after returning to the UK, he discovered that the Sagrada project had got under his skin.

He accepted an internship with the project but spent his first days on the job without a strategy, wondering what he was doing. Then inspiration hit.

“I don’t know where it came from, but I just started thinking of it as a cartographer or a geographer, rather than as an architect – that I was required to map surfaces,” he remembers. Burry realised that he had to treat Gaudí’s shapes as geographical contours in relief.

The fragmented models contained crucial information, so-called triple points, the location at which three surfaces meet. Taken alongside photographic documentation of the lost models, there were enough of these triple points for architectural researchers like Burry to reverse engineer Gaudí’s designs.

“They knew that they had to have progress otherwise it would wither on the vine”

Burry claims the distinction of being the only person in the world to have worked on this problem “in analogue”, using his slide rule to carry out the laborious calculations necessary to recreate Gaudís models. The experience gave him a unique appreciation of the architect’s genius.

“He could conceive of 4D, minimum, in his head,” he says. “For every one of these surfaces, there are nine variables that govern where that triple point will end up […] and I honestly don’t know how we was able to… I mean, it was laborious, it took me months to do each version. It took us months simply to try to get close to the version that he had already done.”

After his internship ended, Burry spent much of the 1980s working as a community architect in the Outer Hebrides, coming over to Barcelona three times a year to help work on the project. Then he got a job in New Zealand and assumed his involvement on the scheme was all but over.

He recalls: “When I came back for this valedictory sayonara, there was all my work out on the table and they said, ‘how did you do this work’? And I explained it to them and their eyes glazed over. They said, ‘I think we need you’.”

It was agreed that he would stay involved with and he was given the task of exploring how computer-aided design could help speed things up. “They knew that they had to have progress otherwise it would wither on the vine,” says Burry.

“They could see that the medieval aspects of building a basilica of cathedral proportions wouldn’t necessarily cut it.”

In those days, the hardware and software necessary to achieve what Burry was trying to do (normal architectural software would not cut it for Gaudí ’s complex geometries) cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and was only used in a few high-tech sectors. So, he spent the next few years visiting boat builders and plane designers to experiment with their tools.

The cost, nonetheless, was prohibitive, until he came across a stroke of luck. “By sheer coincidence it turned out that the Polytechnic University of Catalonia had acquired 10 of these machines with software for no known purpose,” he explains, still slightly incredulous.

Burry became a visiting professor at the university, which became a key partner in the project from then on. It would be years before the methods used by Burry would become common across architecture and construction – Burry himself would use them in his work elsewhere, including doing modelling on behalf of Foster + Partners for the Gherkin building in London.

This high-tech approach was backed by the then-chief architect Jordi Bonet i Armengol (son of Lluís Bonet i Gari), despite the man’s more traditional style. “I don’t know if he even knew how to turn the computer on,” says Burry. “I’ve got lots of drawings of his where it is my computer printer and he has drawn over the top of it.”

Nonetheless, Burry remembers Bonet delivering a stark verdict on his contribution to the scheme: “[He] always said that, if it wasn’t for the computer, the building would have just ground to a halt.”

The person is not important

Gaudí was not the first architect to lead the Sagrada Família project and he knew he would not be the last. However, he may not have predicted quite how many would follow him.

Jordi Fauli i Oller, the eighth architect to lead the project, is a man of modest stature and even more modest personality. When we meet at the Basilica on a warm April afternoon, I wonder aloud what kind of person devotes their entire career to realising another person’s dream.

“The person is not important,” he laughs in response, “but I will answer all your questions.”

Like Burry, Fauli did not hear much about Gaudí as a young man studying architecture. “I knew the Sagrada Família because I was born near here, but in our school – now the School of Architecture – we didn’t receive a lesson about Gaudí,” he says.

Despite, this he was taken on as an assistant to Jordi Bonet, who had become chief architect in 1985 after the two-year reign of Francesc de Paula Cardoner i Blanch. “The reality was very different from today, for example the number of visitors was much fewer, the interest was also fewer,” he recalls, explaining that only a handful of people were working in the office when he started, with fewer than 20 on site.

In the time that he has been on the project, Fauli has had the privilege of seeing the vast majority of the church come out of the ground. As we walk around the basilica, he points out a specific column, the first element he had worked on, and gestures around the space.

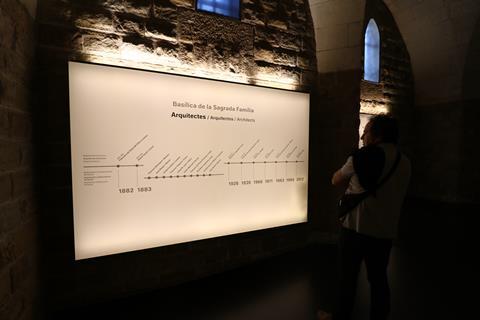

A history of the temple

1882 | Initial designs are drawn up by Francisco de Paula del Villar. The cornerstone of the temple is laid.

1883 | Antoni Gaudí takes over the project after the chief architect and client fall out.

1891 | Work begins on the Nativity facade.

1914 | Gaudí begins working exclusively on the temple.

1925 | The Saint Barnabas bell tower on the Nativity facade is completed.

1926 | Gaudí dies and his disciple Domènec Sugranyes takes over the project.

1936 | At the outset of the Spanish Civil War, the Sagrada Família is vandalised amid outbreaks of anticlerical violence. Plans and photographs are burnt and plaster models smashed.

1939 | Francesc de Paula Quintana takes over site management and leads the effort to reconstruct what had been saved from Gaudí’s workshop.

1966 | Isidre Puig i Boada and Lluís Bonet i Garí take over after Quintana’s death.

1976 | Bell towers on the Passion facade completed.

1978 | Construction begins on the facades on the side naves.

1983 | Francesc Cardoner i Blanch takes over the project.

1985 | Jordi Bonet i Armengol is named head architect and site manager.

1986 | Work begins on the foundations for all the naves, the columns, vaults and facades on the main nave, transepts, crossing and apse.

2010 | Pope Benedict XVI consecrates the Basilica for religious worship and designates it a minor basilica.

2012 | Jordi Faulí takes over from Jordi Bonet as head architect and site manager for the works on the Temple of the Sagrada Família.

2016 | Construction begins on the towers of the Evangelists, the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ.

2020 | The Junta Constructora de la Sagrada Família stops construction due to the covid-19 pandemic. Work resumes in October, focused on completing the tower of the Virgin Mary.

2021 | The tower of the Virgin Mary is completed and inaugurated.

2023 | The four towers of the Evangelists are completed and inaugurated.

“I remember I came here to the nave on the first day with [Bonet] and with the chief of construction and only these windows were finished, only up to this level,” he says, gesticulating. “And only at that moment in the 1990s, these, this, this and the other columns were built – the other did not exist.”

Burry explains Fauli’s role in this period: “He was like the right hand of Señor Bonet and the interface between the university teams and the building teams. We would give the work to Jordi so that he could translate it from AutoCAD to coherent information for the stonemasons.”

In 1986, work began on laying the foundation for the main nave, transepts, crossing and apse, which would take until 2010 to complete, at which point the basilica was consecrated by Pope Benedict. The period also saw the Sagrada given further artistic treatment.

In the late 1980s, Josep Maria Subirachs, a Catalan sculptor who had signed the open letter in the 1960s against the continuation of works, began work on his controversial angular sculptures for the Passion facade.

Further statuary would be completed by Etsuro Sotoo, who left Japan to join the project and was eventually baptised as a Catholic in the church’s crypt, while glazier Joan Vila-Grau created its trichromatic stained glass. After Jordi Bonet’s retirement in 2012, his right-hand man officially took over, as works turned towards the main towers.

Getting the job done

Along the way, there have been many challenges. In one sense, these have been much the same as any construction project would face – access to skilled labour, supply of crucial materials, unforeseen political interventions. But, when a project runs across three centuries, the exact nature of these problems tends to balloon to appropriately grandiose – dare one say biblical – proportions: the mountain runs out of stone, the world is gripped by deadly plague.

The building was originally meant to be made out of Montjuic stone, a particularly durable kind of sandstone found only in the nearby mountain. But the last quarries on Montjuic closed in the 1970s, sparking a hunt for a replacement and creating one of the project’s most persistent bottlenecks in the years that followed.

The project still uses the stone when it can be rescued from other buildings that are being demolished, but incorporates a wide range of toasted fine-grain granites from across the world, including Brinscall Quarry in Lancashire.

In more recent years, the build has been affected by political events. In the late 2000s, as they prepared for the papal visit, the Sagrada was served notice of the city’s need for a high-speed rail link, which would involve burrowing close to the basilica’s foundations. After the project had its petition to stop the works rejected three times, the construction of the tunnel came to pass - luckily without catastrophe.

More disruptive was the global pandemic, which interrupted the flow of visitors to the Sagrada Família. Based on Bocabella’s belief that “providence wants to be built with alms only”, the church had always been essentially crowdfunded. For years, this had contributed to the temple’s slow progress but as it slowly became a global attraction, this weakness had turned to a strength.

Close to five million visitors pay up to €40 to visit, with slightly more than half of the proceeds going towards completing the work. During covid, this strength was undermined, forcing the project to delay the completion date, which was originally meant to be in 2026 to align with the centenary of Gaudí’s death.

Finding people who know how to build church vaults in the traditional Catalan style has been another challenge, and the Sagrada project has helped to keep these traditional methods alive by making itself a place for young people to learn the necessary skills. “In this case we had the luck to have old workers that know this technique and they explain the technique to young workers,” Fauli explains.

“We had in the finish, nine teams to build vaults, with old people and young people that learnt the technique.”

The project has not let itself be constrained by a total commitment to tradition, however. In 2014, with 60% of the building complete, the Sagrada Família approached Arup to help with the remaining structural design.

The project team was concerned that, if the remaining six towers were built in traditional masonry or earthquake-resistant reinforced concrete with stone cladding, it would make the towers too heavy for the foundations and the crypt below.

A solution was needed and Arup came up with the idea of using pre-stressed stone masonry panels as the primary structural element. As well as reducing the weight of the tower by a factor of two, this approach allowed the masonry to be fabricated remotely and lifted into place, reducing build cost and accelerating the construction programme. Arup is now working with the Sagrada Família team on the Glory facade.

Such innovations once again raise questions about the legitimacy of the project. On this point, Burry accepts that the work has not exactly been carried out in the spirit of Gaudí. When I suggest that the architect had been an advocate of new technology in his own day, using the latest photographic tools to enhance his designs, Burry challenges me.

“Not at all, quite the opposite. He argued, I believe, that innovation is something you do in design but not in construction,” he says. “He was a very reactionary dude in many, many ways, not least for his profound religiosity.”

A philosophical matter

It is not just the use of modern technology that is controversial. The authority of the design team has always been subject to much scrutiny in architectural circles, and when Burry talks about the designs for the Glory facade, which the team handed over in 2016, marking the end of his involvement in the project, he hints that there are active debates within the project about this very question.

“[The design] was quite polemical. I’ll be surprised if what gets built is exactly what we handed over.”

Probed further, Burry continues: “My opinion was that the model that was smashed, and the fragments we had was Gaudí’s first and only model for that facade […] I took it upon myself with my team to extrapolate what he would have learnt from that model and imagine how you could clean it up.

“Whereas other people in the office, who are obviously still there now, were nervous, because if we only had these fragments of the original model, surely we should be working only from that? It’s a philosophical matter.”

Burry says he has no idea whether the facade as-built will reflect his suggestions, but he insists that he was assuming no creative licence in making them. “I would argue that, because I’m the only person in the team to have actually worked with the plaster of Paris, I know what the manual process was, as a voyage of discovery not just as a means of representation, and I know how much effort even Gaudí would have gone to in order to get that model made.

“My opinion was that the model that was smashed, and the fragments we had was Gaudí’s first and only model for that facade […] I took it upon myself with my team to extrapolate what he would have learnt from that model and imagine how you could clean it up.”

Mark Burry

“So, I think he would have made another model and another model,” he adds, explaining that, like many Gothic masters, you can see how Gaudí learnt over the course of a project by looking at the development of small elements such as windows.

“I console myself that he would have thought that life is an evolutionary thing – we evolve as humans, so why shouldn’t the window evolve?”

For his part, Fauli seems comfortable that they are honouring Gaudí’s legacy. “We are working – all our teams, the past teams, the past architects – only with the idea to collaborate to build the Gaudí idea. Out of this, the vision is to build the Gaudí idea, to give to the city and to the people from around the world the Gaudí project,” he says.

It once seemed certain that Fauli would be the man to see the Sagrada Família complete, but with covid delays pushing the full completion date back to 2034, this no longer seems inevitable. Nonetheless, Fauli seems to have made his peace with this.

“For me personally, I will be here until God wants – no problem,” he explains contentedly. “[Gaudí] explained that in heaven we will see things better than the Sagrada Família.”

For the most part, what remains to be done is largely a matter of execution, with the last of the architectural work on the Glory facade handed over years ago. This is not to diminish the scale of the task that remains, which includes the construction of a controversial stairway into the main entrance, which would involve the demolition of three city blocks, forcing a thousand families and businesses to vacate.

Nonetheless, the Sagrada still retains a few secrets of an architectual nature. As we descend together from the choral balcony above the nave, Fauli explains to me that Gaudí had wanted to put two large organs inside the cross at the top of the church. I ask him how they are planning to do this.

“We are studying this at the moment,” he smiles. “Another challenge.”

1 Readers' comment