Emma Dent Coad enjoys a book on twentieth-century houses and wonders whether it has lessons to teach us about the current housing crisis

We are living in a time when we are grappling with the mountain of problems caused by a generation of frankly shitty homes. Some were built well but never properly maintained, while others were built quickly and cheaply and are not fire-safe, or leak so much that they threaten building safety and seriously endanger human health and life expectancy.

The Grenfell Tower fire atrocity opened a whole new can of worms, and we are very far from remedying this. All political parties recognize we are in desperate need of more homes, however they envisage funding them and whoever they think they should house. Surely this is a time to reflect.

It may be worth recalling that post-WW2, the provision of housing was put in the hands of the Ministry of Health. Between 1945 and 1950, Aneurin Bevan as minister oversaw the provision of an incredible one million new homes. Housing, health and oversight of local authorities came under the management of a single government department under the stewardship of Bevan.

This makes perfect sense, rather than one Ministry tutting at poor quality housing while another treats rising cases of asthma, tuberculosis, heart disease, and all the other ill effects of poor housing. Some good examples of the Bevan era are included in 100 20th Century Houses, published on 13 October by Batsford for the C20 Society.

As long as there are talented and imaginative architects designing beautiful, people-centred, long-lasting houses and housing, there is surely hope for a future where national and local government will employ them or their successors in the crusade to deliver the millions of safe, healthy, affordable homes we so desperately need.

100 20th Century Houses proves this point with a series of innovative and humane house types stretching from 1914 to 2015, accompanied by essays and texts from writers who know their stuff.

I had only reached page 13 when reality hit. The stunning 1969 house at 60 Hornton Street, Kensington by James Melvin, preserved in cinematic detail in the film ‘Exhibition’, has gone. Its courteous neighbourhood scale and modest facades were set back in deference to the rather loud and rackety brickwork Victorian terrace of Observatory Gardens and middle Hornton Street.

It has been replaced by an overscaled corporate chunk that almost entirely fills the footprint and laughs at its neighbours. I sat on the Planning Committee that determined demolition and development. I voted against both. It still hurts.

On the same page, the refined perfection of the low-key Greenside by Connell Ward and Lucas of 1937 was the subject of years’-long campaigning that I was involved in as a Docomomo-UK Working Group member. Working alongside the 20th Century Society, we fought like demons to save Greenside. And we failed.

There are happier stories among the 100 mostly sublime buildings (not you Poundbury). Some wonderful and innovative houses have been saved for posterity and restored. Some have been refurbished to meet modern needs.

All these buildings reflect the concerns of their times, such as children and servants’ quarters turning into open plan living, where the woman of the house is honoured by modern equipment but is still her own skivvy and cook, and with child-friendly space in the heart of the house at last.

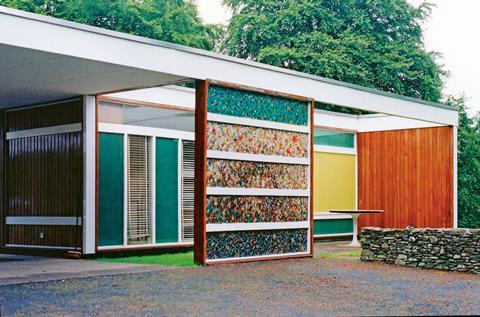

Trying to remain focused in the face of a barrage of heavenly homes isn’t easy. Some favourites are Patrick Gwynne’s 1939 The Homewood, Peter Womersley’s 1958 High Sunderland, and Michael and Patty Hopkins’ Hopkins House of 1976. They are all inspirational private homes, set in luscious nature, with new solutions to co-existence of living and entertaining, and living and working, that are still current and inspirational today.

Some of the tiny homes are exceptional. Jeremy Lever’s 29 ½ Lansdowne Crescent of 1973 is a jewel of a building, where every square inch has been mobilised, similar to Luke Tozer’s 2007 Gap House. Where space is at a premium quite extraordinary solutions come forward to create a sense of order and calm. Surely we could employ more of these solutions in less extraordinary homes?

Homes with glorious expanses of floor to ceiling glazing, some encompassing entire facades such as Hopkins House of 1976, were entirely appropriate when fuel costs were low and climate change unimaginable. How to upgrade a generously glazed building now? In more modest homes, ripping out elegant Crittal windows is no solution.

Some have been assaulted by the virus of UPVC, which in my opinion is an ugly, short-sighted response to the pressing need to improve thermal quality of windows. They are also anti-environment plastic, highly flammable and cannot be recycled. We will regret their wide-spread use in years to come. We need solutions to saving energy that do not create new long-term problems.

The book has some lovely examples of early low-carbon or low energy-use homes, some dug into the earth. Others, like Richard Burton’s ‘long life, loose fit, low energy’ Burton House of 1988, and of course Bill Dunster’s BedZED ‘zero energy development’ of 2002, are really coming into their own. More please.

On that front we do need, and soon, reliable and standardized ways of monitoring claims of zero or low-energy buildings. We should not allow developers to make outlandish claims, when apparently only 29% of new buildings actually attain the low energy use they state.

In Kensington and Chelsea, as elsewhere, we are faced with the imperative to provide more homes. The need, as ever, is for ‘affordable’ housing, though to whom they are affordable is an ongoing debate. The solution, to my mind, is absolutely NOT to build high. Tall buildings are exorbitantly expensive to build, to service, to make fire-safe, and to heat and cool.

The answer is not to provide heating, aircon and sprinklers, which merely mitigate the problems the buildings create. For me, a generation of mid-rise high density housing, built solidly with safe insulation, natural through ventilation, triple glazing and private outside space is a model well worth revisiting.

I am thinking of Neave Brown’s Alexandra Road (not published here) plus the wonderful Branch Hill by George Benson and Alan Forsyth of 1978, ‘public housing’s swansong’, as the following year Thatcher won office and stopped council house building. Branch Hill, Alexandra Road, and the Whittington Estate (’Highgate New Town’) surely merit further study if we are to build a new generation of good quality homes.

It might be a stretch to say that in 2022 and beyond, we have been dragged back to a post-WW2 situation. But the house building and construction crisis brought on by a combination of Brexit chaos, Putin’s war with Ukraine, and blatant developer greed, does have similarities, along with the shortage of materials, skilled labour, public funding and frankly the will of the incoming government.

Recent proposals to house street homeless in converted shipping containers, or pre-fabricated pods, are less generous than the 156,000 pre-fab bungalows built after the war, with their gardens big enough to grow veg. Nearly 80 years later, have we gone full circle? Or can we learn from some of these intelligent and thoughtful homes, and truly build economically, environmentally, and better long-lasting homes?

Postscript

100 20th Century Houses by Twentieth Century Society is published by Batsford.

Emma Dent Coad has been a local Labour Councillor in Kensington and Chelsea since 2006, and is currently Labour Group Leader and Planning spokesperson.

She was Kensington’s first Labour MP from 2017 to 2019.

1 Readers' comment