Matthew Lloyd appreciates the production quality of a new book on RIBA award-winning houses, but wonders what happened to the floorplans

This is a book aimed at people interested in RIBA award winning houses in Britain, built over the past ten years or so.

The book is divided into two, the first part being descriptions of the houses themselves, with chapters arranged by geographical region: a reflection of how the regional judging at the RIBA is divided up.

The second part is a short guide to working with architects. In this way, 21st Century Houses is aimed squarely at the public, rather than we architects ourselves. The book conveys a sense of quality sitting next to you on the desk and is substantial at more than 300 pages.

The first chapter is set in the South (of England) and starts strongly with the Cork House from 2019 by Matthew Barnett Howland and Dido Milne, located in the shadows of Eton school. This simply shaped, bee-hive roofed building was the result of a research project carried out over 5 years. As an architectural reader, I was immediately desperate to see a plan drawing to understand how it all worked, but more on that later.

Another very low energy house comes next, Lark Rise by Bere Architects’, and acts as a test case and benchmark for advanced PassivHaus design, however austere the house is itself.

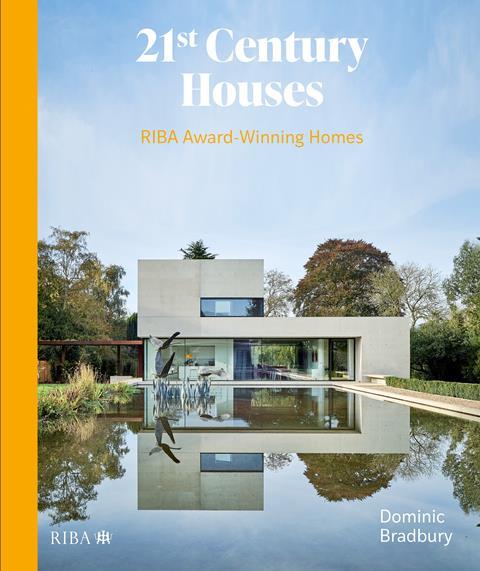

There follows a clutch of linear, flat roofed houses, by specialist architects like Gregory Philips and John Pardey. These show the still enormous influence of mid-century modernism in the design of these sorts of large, opulent country villas. The Pheasant House by Sarah Griffiths and Amin Taha stands out here, with its sculptural garden elevation set against a pool, an image that also adorns the book’s cover – although strangely there are no interiors of this house shown.

In the next South East chapter, the Harbour House Chichester by McLean Quinlan has an authenticity and empathy for its setting that makes you pleased you studied architecture. And the Caring Wood house in Kent by James Macdonald Wright and Niall Maxwell is a brilliant, poetic take on the traditional oast house.

There are various other houses in the book that use vernacular forms, including another oast-type complete reimagining by ACME and several using the now familiar barn typology, notably the minimalist Hill House Passivhaus by Meloy Architects. Likewise, the black-clad North Vat house by Rodic Davidson, with magically identical sloping roofs and walls (and the illusion of no gutters), is highly appropriate for the aura and gloom of Derek Jarman and his beloved Dungeness.

Le Petit Fort in Jersey by Hudson Architects seems, despite its name, large and exclusive, and without interiors or a plan to explain this house, it is hard to appreciate.

Alison Brooks’ Windward House is so unpredictable, geometrically unexpected, original and yet for me understated too – that I do gasp at this piece of design. Brooks, like many very good architects, can shift scales from big housing schemes or Oxford colleges, right down to this domestic scale. It would be an essay in itself, to explain how some architects can do this shifting of scale so well. And hurray, there are plans here too, essential to understand how this complex house is arranged.

Moving to the London chapter, with the inherent density constraints of the location, the mood changes. The predominance here is of infill, end of terrace, yards and back-land plots. This is a surprisingly small chapter given the sheer number of architect-owned/designed homes you see on these tight sites in the city. Jonathan Pile’s house in south London stands out for its timber framed innovation in a congested setting: I would most surely like to live here myself.

Then there are houses by the super-contextualists here, like Chris Dyson, who carves his buildings so superbly out of the very walls of historic London. DSDHA’s white clad self-build garden house in stark contrast is unashamedly modern. In a further contrast of architectural language, Henning Stummel’s Tin House for his family breaks any mould we would recognise, with unusual tin-clad huts arranged around a tucked away site in Shepherd’s Bush.

Moving out to the East of England, we arrive in an agrarian context, with wide skies and stark agricultural references or bleak estuarian places with seawater lapping at building edges. For me a standout exterior here is Blee Haligan’s Five Acre barn, a shingle clad run of ziggurat roofs in a woodland setting. I am also engaged by Lisa Shell’s tiny Redshank house, a box on stilts over water with a raw exterior, mimicking a bird hide with similarly basic interior – there is an absolute economy here, a little hideaway, in such contrast so many of the projects in the book.

The final project in East Anglia is eccentric, indeed so unexpected that I don’t wonder at the RIBA’s decision to award it a prize. Tonkin Liu’s Water Tower project is literally just that. Eccentric, audacious and bleak, but nonetheless magnetic.

It’s only when we arrive at the East Midlands that the book seems completely honest about construction costs, as I sense that many of the values in the book are surely understated. So here in Northamptonshire James Gorst has created Hannington Farm for the tidy sum of £6.3M – which to be fair includes various ancillary buildings. But the traditional materials are superbly well used, and the monastic interiors church-like and almost medieval. I wouldn’t pay £6m for this house, but I would pay a lot for a building that will stand the test of time like this.

Actually, do we mind if something costs a lot if it results in great architecture? I can’t imagine that this year’s Stirling Prize winner, the library at Magdalene College, didn’t cost a fortune, to then only serve a handful of lucky Cambridge students. But the money was worth it, creating a building of national and perhaps even historic significance.

At completely the other of the scale, in the West Midlands section a little Corten street house extension in Shropshire by form:form architects shows significant architectural skill out of a tiny budget.

The best house in the North of England is Bennetts Associates’ House In Cumbria, so contextual to an unnamed stone-built town as to be hardly seen. This is well judged contextual modernity.

In Yorkshire, Tonkin Liu break the mould again with their Old Shed New House, an extraordinary home based on a love of books, set within a reinterpreted agricultural barn form. I also like ID Architecture’s Barrow House, typologically another barn house, but unexpectedly sitting on a modern concrete base, as though two houses in one. But from a distance this dwelling still sits nicely in the landscape.

The Welsh chapter is refreshingly rural. Lovely houses here by Hall+Bednarczyk and Martin Edwards are rightly contextual in their country surroundings. The latter is mesmerizingly modest and simple.

In Northern Ireland the selection of houses is presentable but lack distinctiveness. However, in Scotland an outstanding new tradition of brilliant, contextual retreats and coastal homes by the likes of Mary Arnold-Foster, Dualchas and Denizen Works bring the book to a strong conclusion. These often-modest houses are arguably the best building type being produced in the Scottish context nowadays.

21st Century Houses is probably not a book I would choose to buy. It lacks a single, compelling story and the houses here are too varied in quality. Edited much further down, and the number of houses perhaps halved, with proper architectural drawings, and there would be a clearer project here. So a far more honed book by the same team, more deeply analysing contemporary British domestic architecture at its genuinely most excellent – which I think it actually is – would surely have architects buying it in their droves whilst still remain appealing to a wider audience.

Although the book production itself is attractive and the buildings are well described by Dominic Bradbury. But you’d expect at least this by the RIBA, wouldn’t you.

Postscript

21st Century Houses by Dominic Bradbury is published by RIBA Publishing

2 Readers' comments