Hugh Petter’s work offers a much needed riposte to the orthodoxies of much architecture and urbanism over the last 60 years, writes Nicholas Boys Smith

The Accidental Radical

As Hugh Petter, whose remarkable body of work is the subject of Living Tradition, writes, “before cheap fossil fuels, vernacular buildings and old towns were intrinsically sustainable because they could not have the luxury of being otherwise. There is much to learn from the past to help inform the future.”

The profound sustainability of traditional place-making might almost be the theme of Clive Aslet’s book. It is the sustainability which seeks to create buildings which can last and places in which you can walk to the shops in the place of more heavily-marketed green bling.

How, asks Petter’s work, do we create townscapes that are in harmony with their landscape? How do we create places that are in communion with the past, present and future? How, by learning from our forebearers, can we create homes for tomorrow? And how can what we create be of solace to future generations whose lot may be more wearisome than our own?

Everything about Hugh Petter is a paradox: a comprehensive school boy who designs to the manor born; a bridge-builder who challenges the orthodox; a conservative who keeps being radical; and a self-effacing man who has master-planned the most influential British urban extension of the last 15 years.

To wander around Nansledan, the thriving urban extension to Newquay which Petter conceived alongside Leon Krier for the former Prince of Wales, is to be reminded of the continuing relevance of traditional urbanism. It stands as a radical riposte to everything that has gone wrong with place-making over the last 80 years.

Its morphology and street design, its buildings’ typology and manner breaks every single post-war orthodoxy and most of the norms of today’s housebuilders, highways engineers and master-planners.

There is no ring road round the edge but a high street through the middle; there is no commercial zone on the periphery but shops and offices throughout; there are no cul-de-sacs but streets and squares; little ‘on plot’ parking but many private mews; no rounding splayed junctions for cars but tight corners for people.

Most provocatively of all there are neither the featureless facades of the urban architect nor the ersatz vernacular of the volume housebuilder but street upon street of modest Cornish vernacular, timeless because it might have been built 200 years ago and will still be with us 200 years hence. Both the living tradition, of the book’s title, and a profound reproach to the unsustainable ‘traffic modernism’ of the twentieth century.

The first phase of Nansledan works better than the first phase of its Dorset predecessor, Poundbury, because it is trying less hard. It is calmer with fewer house types and better controlled parking. The Duchy of Cornwall is getting more skilful.

The figures speak for themselves: almost immediately homes in Nansledan were achieving a 20 per cent price premium over other new builds on the outskirts of Newquay. It’s easy to see why.

As one resident told me a few years ago: “you feel like you live here as an individual, not a number. That feels good. We pretty much know all our neighbours.”

Petter has worked to convey traditional and sustainable skills and urbanism beyond Duchy of Cornwall land, leading the creation of a splendid master plan in Oxfordshire, overseeing the design of a range of James Gibbs inspired porches and encouraging master craftsmen and young architects through the Georgian Group, the Art Workers’ Guild, the Building Crafts College and the British School at Rome.

Petter‘s best work is calmly classical or richly vernacular, at once self-effacing and playfully confident; the clapboard in a Hertfordshire landscape; the cottage orné in the Yorkshire woods; the hung tiles in a Sussex Garden; a Doric door to a Hampshire manor house; or the granite sills and seaside colours on a terrace of Cornish cottages marching in line with the hedge that predates them.

I particularly like his restorations where his temperamental diffidence and scholarship allows him to work calmly and knowledgeable with what is already there. His communions with Lutyens at the British School of Rome, at the former Midland bank on Piccadilly and, less directly, in the Hertfordshire countryside is particular happy.

His least good work is where the brief is immodest. I personally would take out a pediment or two though I suspect their insertion may have been at the client’s request.

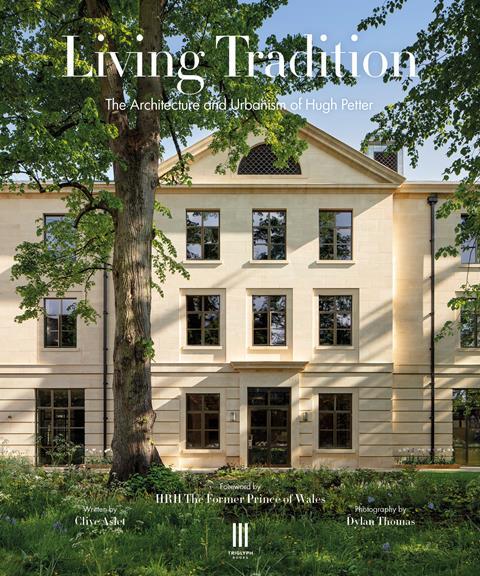

Clive Aslet’s study of Petter’s oeuvre is appropriately low key. Aslet’s fine narrative, his clear descriptions and the luminous and lovely photos of Dylan Thomas play subsidiary fiddles to Petter’s melodies as they should. However, they do highlight just how much prejudice Petter had to ensure during his education and in the early portion of his career before he joined Robert Adam in Winchester at what was to become ADAM Architecture.

Whatever your architectural preferences Petter’s flinty and good-humoured determination to take his own course and to find the instruction that he needed is remarkable. He says calmly of one incident where he was, unfairly, nearly failed by dogmatic tutors, “It is quite amusing now, but it certainly wasn’t at the time.”

Hugh Petter will probably never be famous amongst the wider public. He does not seek fame. Nor I suspect will he ever be revered by his own profession. But he should be. He is doing more good to our landscape than some more famous names who have shot garishly across the firmament.

Petter’s architecture is good and green not because he is clever but because he is wise. Living Tradition explains why.

Postscript

Living Tradition: The Architecture and Urbanism of Hugh Petter by Clive Aslet is published by Triglyph Books

Nicholas Boys Smith is the founding director of Create Streets and chair of the Office for Place

No comments yet