David Hare’s Straight Line Crazy is a powerful production that examines how an unelected planner can use his influence to affect millions of lives, writes Thomas Lane

The playwright David Hare is a skilled master at unpicking complex topics and bringing the people involved alive, giving the audience an understanding of the dynamics behind these issues.

These include The Power of Yes, which untangled the financial crisis of 2008, and the Absence of War, which observed how the internal workings of the Labour Party leadership contributed to its 1992 election defeat.

In Straight Line Crazy Hare turns his attention to Robert Moses, the unelected urban planner who was the biggest single influence shaping New York from the 1920s to the 1960s. This work should interest anyone interested in the forces that shape cities and, although the time period covered by the play spans from the 1920s to the1950s, the issues it raises are still pertinent today.

It looks at Moses’ fixation with building expressways and focuses on two key events during his reign – the construction of expressways on Long Island in the 1920s enabling New York City workers to access the beaches and parks of Long Island and, later, the opposition, led by Jane Jacobs, to his plans to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway which would have sliced through Greenwich Village and SoHo.

Ralph Fiennes gives a superb performance as the driven, single-minded and arrogant Moses. Moses believed strongly that working people should be able to access Long Island, which at that time was owned by wealthy families including the Vanderbilts and JP Morgans who did not want the great unwashed sullying their private paradise.

Moses started work on the roads without authorisation despite the high probability of losing a court case brought to stop the appropriation of land for the project

To achieve his aims Moses started work on the roads without authorisation despite the high probability of losing a court case brought to stop the appropriation of land for the project. Governor Al Smith, played with aplomb by Danny Webb, has the ear of the wealthy Long Islanders and is furious with Moses when he finds out.

In a compelling scene Moses engages his charm to persuade Smith that electorally it is in his interest to support the project and suggests that Smith takes the judge presiding over the case out to lunch to persuade him of the cause. Ultimately Moses triumphs and the roads are built.

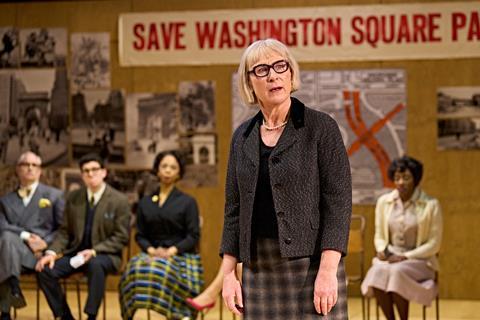

In the second half Jane Jacobs comes to the fore to oppose Moses’ plans to build a four-lane highway 30 years later through Manhattan’s Washington Square Park in the heart of Greenwich Village. Moses dismisses Jacobs and refuses to engage with those protesting against the plans.

During the confrontation it is revealed that Moses, who started off by championing the rights of working people to enjoy a better life, deliberately ensured the Long Island bridges were too low for buses carrying those unable to afford cars and the network of expressways that he built carved through the poor tenements occupied by black and Hispanic people. And people were beginning to realise that building new roads made congestion worse, not better, by attracting yet more cars onto them.

His self-belief and intransigence combined with the dulling of his political antennae, mean that in the end he fails

His own team – Ariel Porter, played by Samuel Barnett and Finnuala Connell (Siobhán Cullen) – try telling Moses that the world has changed and that he needs to listen to and engage with people’s concerns. But his self-belief and intransigence combined with the dulling of his political antennae mean that he doesn’t, and in the end he fails. The opposite happens and all motorised traffic is banned from Washington Square Park.

The second half is less coherent than the first as it is trying to deal with so many issues, including the exposure of Moses’ multiple flaws.

But, overall, this is a powerful production and a reminder that these issues have not entirely gone away. Fortunately urban expressways are history – London had similar battles in the 1960s, for example the London Motorway Box, otherwise known as Ringway 1, would have destroyed swathes of north and south London had it not been stopped although not before the east and west cross routes were built.

Today the battle is persuading people out of their cars to walk and cycle instead to cut pollution, global warming and obesity. But this is proving controversial leading some local authorities to resist the building of new cycleways on their patch. Some others have ripped out low traffic neighbourhoods despite local support for these schemes.

If the story of Straight Line Crazy is anything to go by, it could take another 30 years to make these changes stick.

Postscript

Straight Line Crazy is at the Bridge Theatre in London until 18 June and will be streamed by NT Live on 26 May

No comments yet