Andy Foster reviews a new book celebrating the work of one of the Midlands’ pre-eminent modern architects

Richard Twentyman was a fine mid-twentieth century architect who deserves this good book. He came from, and worked in, Wolverhampton, the least regarded of large Midlands towns. (It was the largest place in England that was not a city, until it finally gained that status in 2000.) His training was unusual for the area.

Most local architects between the wars went to the Birmingham school. Twentyman, from a wealthy family, read engineering at Cambridge and trained as an architect at the Architectural Association from 1932. The attitudes he developed from this, as well as an engineering approach and a progressive architectural outlook, lasted him a lifetime.

One unremarked influence on him is always the heroic age of engineering in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. From the late thirties to the early sixties he was arguably the most forward-looking architect in the region. Only W.T. Benslyn of Birmingham could equal him there, and Benslyn died relatively young.

He was not what you might expect: shy, amusing with friends, a lover of fast cars and playing bridge. He and his younger brother Anthony, a sculptor, “lived together for all their lives from the war onwards”, after 1958 at Claverley in Shropshire, and “were regarded as an eccentric institution”. He is best known for his series of churches: the subject of this study.

With his progressive architectural stance, they suggest, perhaps, someone mildly left, and perhaps a liberal Anglican. He was the exact opposite: right-wing in politics and – these comments are from a friend who was a practising Anglican – “considering the number of churches he designed, he was quite famously anti-clerical.”

In later years he went into the office by ten or ten-thirty. It was quite a small office: in the sixties, after Geoffrey Percy’s early death, just Twentyman, John Hares, and an assistant architect, George Sidebotham. “At lunchtime he went to the Conservative Club for a meal and a sleep” – he had no domestic skills – “returning to the office about 3 o’clock”. Then he worked until about six. Yet he designed all the buildings.

The early ones, St. Martin, Dixon Street, Wolverhampton and St. Gabriel, Fullbrook, Walsall, both of 1938-9, attracted Pevsner in his 1974 guide to Staffordshire (under the firm’s name, Lavender & Twentyman), but with a rather rigid chronology he says “1939 is just a little late for all this; if it were of 1933 it would be remarkable – at least in England”.

Kennedy and Ridyard are more concerned with a proper analysis of their antecedents: the influence of Sweden, of Dudok, and of English architects like F.X. Velarde. Wolverhampton, as they say, already had the very Swedish Civic Hall by Lyons and Israel, designed in 1934 and completed in 1938 (and recently wrecked inside by the city council).

Swedish influence locally was not new. It starts with the municipal complex in Dudley by Harvey and Wicks of 1926-35, and all of it is indebted to Ahlberg’s Modern Swedish Architecture of 1925. Twentyman’s designs, though, strain hardest towards Modernism, with their cubic brick shapes, plain windows, and beamed ceilings. Only the unmoulded round-arched arcades nod towards contemporary Anglican Early Christian Revival; and here I’m not sure Kennedy and Ridyard are quite right.

They make a break at this point, marking ‘A Change in Style’ with Twentyman’s early Modernist industrial and commercial buildings, an ice-cream factory of 1934, now demolished, and the Wolverhampton gas offices of 1938. They have indeed no historic detail at all, though the early factory has Moderne swept corners.

But the idea of modern in the mid twentieth century was a moving target. The simplified, Swedish influenced buildings of the decade after 1925 before were seen as modern when they were built, just as the churches and the gas offices were just before the Second World War.

The churches are challenging compared, for example, to the two best Birmingham architects of the thirties, both older: E.F. Reynolds and Holland Hobbiss. Hobbiss’ allusive late Arts and Crafts designs are careful of detail but breathe history. Reynolds is more obviously progressive. The interior of his St. Hilda, Warley Woods of 1938-40 is very spare; but not as far forward as Twentyman’s designs.

Twentyman’s postwar churches are different, and the fundamental change, as Kennedy and Ridyard notice, is structural, a matter of his engineering background: the use of reinforced concrete frames and brick skins. That results in a lighter aesthetic, a contrast of brick panels and large framed windows. Massiveness drains slowly away.

All Saints, Darlaston of 1951-2 – an unusual date for a church, its predecessor destroyed by bombing – still has hefty transverse walls defining the interior space. They are pierced by segmental openings for passage aisles, and these in turn reflect the segmental ceiling, a satisfying effect.

Emmanuel, Bentley of 1956, perhaps his finest work, uses quatrefoil concrete columns to separate a wide north aisle. After St. Martin’s hefty ceiling and All Saints’ piers, they seem almost weightless. The whole interior, even the boarded ceiling, is light and airy. As a counterweight there is a heavy, tapering, asymmetrical tower which unusually shows the influence of Dominikus Böhm.

His other churches can only be mentioned briefly. St. Nicholas, Radford, Coventry of 1954-5, currently disused and awaiting demolition, is the most experimental, with its side walls sloping at 10 degrees, and reflected in the slight entasis of the tower: a typical Twentyman subtlety.

His smaller churches at Castlecroft of 1955, and Rubery of 1960, are convincing designs. Castlecroft is now very rare as a mission church surviving with all its fittings.

All these churches are contemporary as architecture, but conservative liturgically, with traditional aisled naves and chancels, though the altar is always completely visible to the congregation. Kennedy and Ridyard rightly mention the growing influence of the Liturgical Movement and the work of Peter Hammond.

They say tactfully that what Hammond would have thought of Twentyman’s churches is “not clear… it may be that Twentyman does not meet Hammond’s stringent requirements regarding liturgical function.” This is true. Hammond’s dogmatic mind would have thought them, in his own words “mediaeval churches masquerading in contemporary fancy dress”.

It takes an effort now to understand the fifties Church of England: confident, rather Low, conservative but not reactionary: the era of C.S. Lewis, full churches for Evensong, woollen sweaters, duffel coats, and “Bash camps” for young people. Twentyman’s superb churches fit it perfectly and still summon up the period instantly.

The industrialist Alfred Owen and his family, who paid for Emmanuel, were part of this milieu, organising Christian young people’s summer camps at their home, New Hall, Sutton Coldfield. In a pleasant gesture, the book’s preface is by David Owen, Alfreds Owen’s son, well known locally for his involvement in conservation over many years.

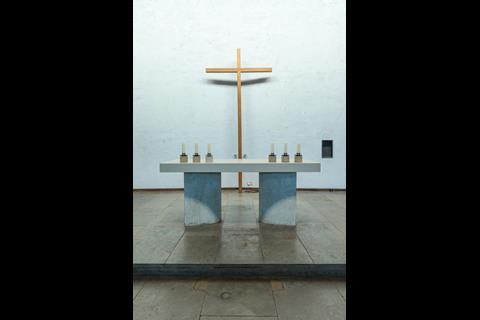

Twentyman’s last church designs, St. Andrew, Runcorn, and St. Andrew, Whitmore Reans, Wolverhampton, of 1965, show him reacting to the radical sixties, and his acceptance of the ideas of the Liturgical Movement. They have forward altars with the congregation surrouning them.

St. Andrew’s at first glance is a simple rendered square inside with just the wonderful blue John Piper window, and the hidden lighting from towers along the sides. This suggests, as the authors say, Louis Kahn, but George Sidebotham always maintained it was a reflection of Ronchamp.

If you stand or sit a while, however – which, whatever Twentyman’s religious views, is what his churches are made for – the building reveals a remarkable and deliberate numinous quality. Each wall was plastered in a single job, with eight or nine plasterers on a cradle starting at the top and not stopping until they reached the bottom.

The result is completely smooth walls without any ridges or joins. They have a otherwordly, almost uncanny feel (and are very vulnerable to modern alterations). Detail is rarely more exiguous, yet more effective.

…he left a wonderful body of work, always worth that second and indeed many more looks

The photographs on pages 157 and 158 bring this quality out well. This will not surprise Twentieth Century Society members, as they, and the rest, are beautifully taken by John East, who is something of the Society’s resident photographer.

Among others it’s worth mentioning the interior of Emmanuel taken from the aisle – an old habit of photographers of ancient churches, but something less common, and effective, here – and the beautiful gradation of light which brings out Twentyman’s decorative east walls so well at Emmanuel and Rubery.

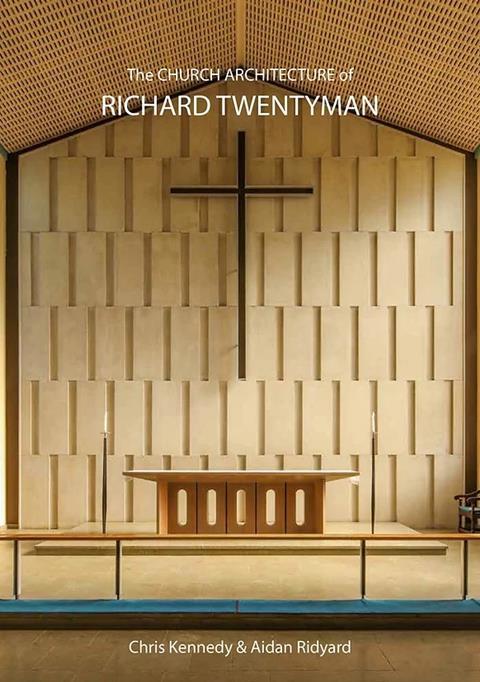

It is his mastery of composition and perfectly calculated detail which distinguishes all Twentyman’s work. His church fittings are exemplary and the east walls of the fifties churches have a series of wonderful abstract patterns in relief, both rhythmic and restful. He could place masses together with an unerring hand. The gas offices first show this, and it runs right through to the end of his life.

His police station in Wednesfield of 1971 is at first sight a brick-faced concrete sandwich on a bleak relief road. Then you see the skill with which the building is composed. Churches were only one part of his practice and it is tragic that so little of his secular work survives unaltered: not one, for example, of his numerous schools.

Charles Mason, the founder of the Wolverhampton practice Mason Richards, who started in Twentyman’s office, said that he was “a strange man really, not good at communication, a bit of a loner, not particularly friendly”. Mason said he disliked being called “Mr. Twentyman”, and perhaps it’s significant that George Sidebotham, who worked with him for many years, always drily referred to him as that.

But he left a wonderful body of work, always worth that second and indeed many more looks, and this book is an excellent introduction to it.

Postscript

The Church Architecture of Richard Twentyman, by Chris Kennedy and Aidan Ridyard, is published by Forest of Arden Press

Andy Foster is an architectural historian and author of the Birmingham Pevsner City Guide and the Pevsner Buildings of England architectural guide to Birmingham and the Black Country

No comments yet