Ben Flatman speaks to architect Annabel Karim Kassar about how history, identity and loss are interwoven in her latest work about a house in Beirut.

The huge explosion that ripped through Beirut’s port and urban core on 4 August 2020 has come to symbolise the city’s slide into despair. Blamed on corrupt officials and lax regulation, 2,750 tonnes of poorly stored ammonium nitrate produced one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history.

More than 200 people died, and 300,000 were displaced or left homeless. According to Annabel Karim Kassar, the architect behind a powerful new installation at the V&A, 1,500 historic houses were also severely damaged, some beyond repair.

Beirut is one of the longest continuously occupied cities in the world. Its roots go back 5,000 years to the time of the Phoenicians. It has endured millennia of occupations and civil war. It would be foolhardy to predict its imminent demise. And yet the current economic and political crisis in Lebanon is testing the city to its limits.

The country’s problems are complex and can sometimes seem intractable. Corruption and misgovernment have sunk the majority of the population into poverty. Families barter what little they have for fuel and food. Many of those who can are looking for ways to leave and join the huge global Lebanese diaspora.

It is against this background that French-Lebanese Karim Kassar’s installation seeks to highlight not only the plight of her adopted city but the intricate web of emotion and identity that ties people to specific places.

Karim Kassar worked for Marcel Breuer early in her career and began her private practice in 1982. After winning a joint competition with Valode & Pistre to restore Beirut’s war-ravaged souk, she moved to Lebanon and established Annabel Karim Kassar & Associates there in 1994.

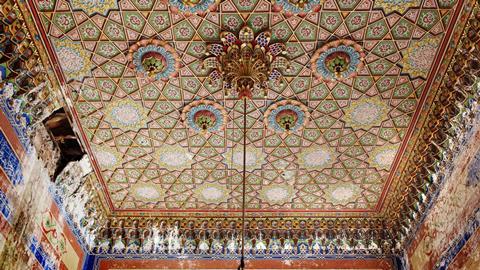

Her work combines a love for the city’s historic buildings with a passion for contemporary design. For years she has worked on a mix of conservation projects, new-build commissions and furniture design. A recently completed project was Bayt K, a historic house restored as a family home and community hub.

Although entirely sympathetic to modernism, Karim Kassar also believes that architects have much to learn from traditional design and construction methods. She speaks often about the importance of the local craftsmen with whom she has worked in Beirut and on this new installation.

It was this love of old buildings and strong commitment to their restoration and survival that led her to buy a dilapidated house in the heart of Beirut’s old city. Close to completion in 2020, it was devastated by the explosion. Friends of hers were also among those who died.

When she originally bought the rare Ottoman-Venetian style house, she had the intention of living in it. Today her plans seem far more circumspect – reduced to simply shoring up the structure and ensuring that it is not completely lost. “It is no more a place,” she tells me, and has “no intention to live in it for now.”

Karim Kassar has used the opportunity to exhibit at the V&A as a means to step back and contemplate not only the house but the wider story of the city’s repeated setbacks and sense of loss. She tells me it was “part of my duty and emotional state to bring these memories to London”.

The main focus of the installation is a reconstruction of a section of her house within gallery 127, the “architecture landing” of the V&A. It mixes salvaged fragments with newly cut stone and replica elements. Although strangely sanitised in this context, the overall impact remains powerful.

Bits of dislodged fresco from the house’s ceilings are laid out nearby. And an Ottoman daybed invites us to lie back and contemplate what has been lost, and that which may yet be saved.

A series of videos that sit alongside the installation tell the stories of ordinary Beirutis, including their experiences during the explosion and resilience since.

There is a deep sense of sadness that pervades the films. What comes over most strongly is a sense that these people are in many cases just surviving. The blast clearly left a wake of psychological devastation, as much as it wrecked the city’s physical fabric.

When I ask Karim Kassar what her own reaction was to the blast and the damage it caused to her house, she says it is “emotionally very difficult. It really makes you feel so empty. It builds a hard place inside people.”

When there has been so much death and human suffering, Karim Kassar is often asked why she is focusing on the conservation of houses. By way of explanation, she tells me that there “is so much memory for generations in houses. In all cities destroyed there is a hole. It takes two or three generations to recover.”

I would like to carry on restoring. More slowly. Piece by piece

Saving what’s left and starting to rebuild is her way of healing the wounds, both physical and spiritual, that she so clearly perceives around her.

Karim Kassar’s work is an articulate reminder of the way in which our sense of identity is so often closely connected to place and history. Despite her own personal reticence, this installation speaks loudly of the inner trauma experienced by those who have lived through the violent destruction of their built environment.

It is of course not a new phenomenon. In fact, Beirut, with its dense layers of inhabitation, destruction and rebuilding is more familiar with such cycles than most other cities. Karim Kassar even at one point describes the 2020 blast as “Just another disaster.”

But the message resonates particularly strongly at a time when Syria has recently experienced such extensive destruction, and we witness towns and cities damaged or obliterated in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

What now, I ask her? “I would like to carry on restoring. More slowly. Piece by piece.” This, I sense, is the only way that she can process the devastation and grief around her.

Postscript

The Lebanese House is at the V&A on the Architecture Landing, Room 127, until Sunday, 21 August, 2022

No comments yet