David Frazer Lewis reviews Edmund Harris’s new book, which delves into the lives and designs of three Victorian architects whose bold, unconventional take on Gothic architecture both shocked and fascinated their contemporaries

When the Strand Music Hall opened in 1864, it caused a storm in the architectural press. In a letter to the Building News, leading ecclesiastical architect J.P. Seddon condemned its “eccentric proportions” and “puerilities in the details”. Many others wrote in, and although they varied in their reasoning, they largely reached a similar conclusion: the building, especially its exterior, was simply ugly.

The architect, Bassett Keeling, replied that he was not aiming at “the smooth and limpid harmony” of good taste. Rather, he sought an effect that drew attention. He said it would indeed be unfortunate if many buildings like this were built, but no one could deny its originality.

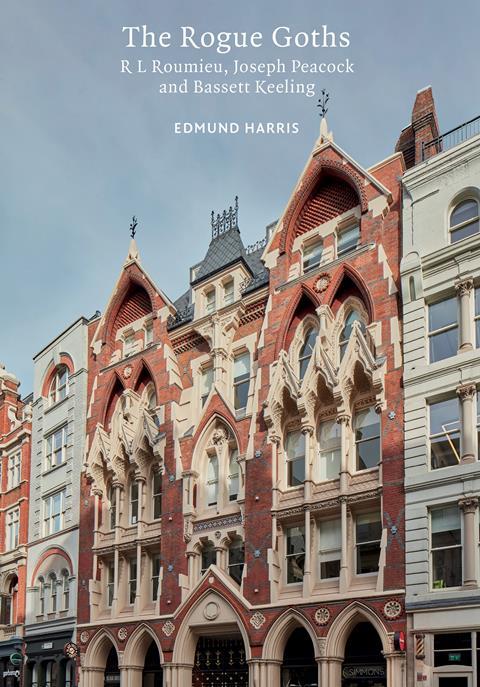

Keeling was what the author, Edmund Harris, has labelled a “rogue goth”: a High Victorian architect who peddled a loud, brash, and strange strand of the Gothic Revival. Three of these rogues – Keeling, R.L. Roumieau, and Joseph Peacock – form the subject of this book, the latest in the Victorian Society’s well-produced and affordably priced Victorian Architects series.

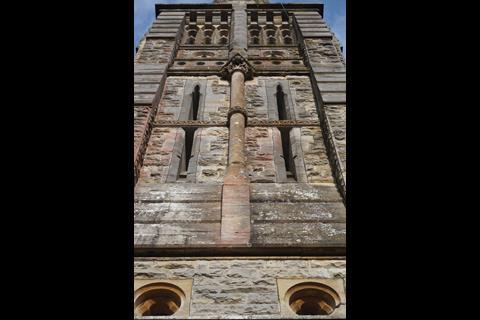

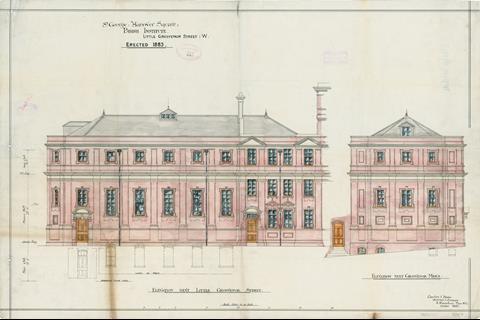

The buildings are indeed striking, notable for their wilful disregard of proportion, strange contrasts of scale, spiky skylines, sharp angles everywhere, and polychromy in the colours of mustard and ketchup. The author does not expect us to necessarily be sympathetic to this. His descriptions frequently use words such as “disturbing”, “frantic”, “mangled”, and “perverse”.

What is boggling is that these structures were built at all, and that their architects made a career of designing them. Harris, the writer of the popular blog Less Eminent Victorians, delves into this mystery, deducing what he can about the clients, lives, and motivations of these curious architects. By doing so, he gives us new insight into Victorian culture.

The book is full of characters with names like Sextus Hexagon Dyball and Clapton Crabbe Rolfe. It puts one in mind of seedy pubs, opium dens, and the Flashman novels.

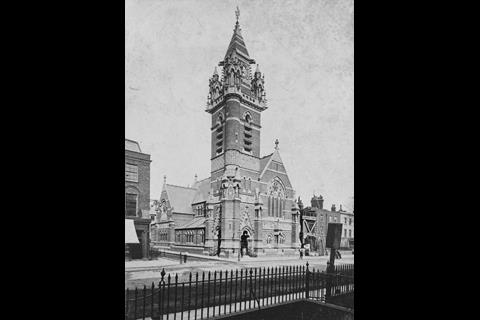

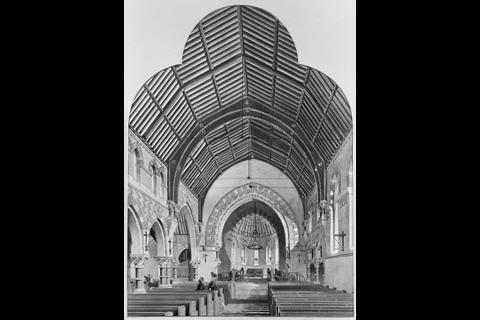

Some of the buildings discussed truly feel astonishingly “off”, such as St George, Clapham, with its ceiling beams decorated with notches that, to me at least, evoke a giant yawning mouth full of sharp teeth. Many of the buildings, having for some reason been demolished, can only be illustrated with black-and-white prints in an Edward Gorey style.

Before reading this book, I had mainly encountered such rogue Gothic in America, where I had assumed it was a product of having read Ruskin without ever having seen a Gothic church. Undoubtedly, much American Gothic of this period is very good, such as the work of Frank Furness or William Appleton Potter, yet there has always seemed a surfeit of piled-up crashed-together compositions like the work of Willoughby Edbrooke or the strange Wizard of Oz courthouses found in so many American town squares.

But Harris reveals that lots of architects were doing this on purpose. And they were even doing it in Britain, where they had plenty of examples of real medieval architecture and elegant Gothic Revival close at hand.

These architects undoubtedly had brio. They had vigour and go.

What is boggling is that these structures were built at all, and that their architects made a career of designing them

And some of these wild practitioners of untamed Gothic were quite good despite it all – S.S. Teulon, for instance. Harris chooses to focus on three of the more questionable ones, for the simple reason that we are more likely to learn something unexpected, and because, in their way, they are the most fun.

In the end, was the Strand Music Hall as bad as its critics made out? The entire auditorium ceiling was constructed of panels of stained glass, and the gas jets shining through its kaleidoscope of patterned and jewel-cut surface were the sole source of nighttime illumination. Even its detractors had to admit that the effect was interesting.

Another point in its favour was that the carving of its façade was executed by James O’Shea, the craftsman of some of the finest architectural stonework of the era, including many of the capitals of the Oxford Museum. Some of its “puerilities” must have at least been entertaining.

In the end, however, the venue did not prove popular and had to close after only two years. Did the intensity of the architecture contribute to its failure? It is hard to say.

>> Also read: Architecture Book of the Year Award 2024 winners announced

>> Also read: The Ingenious Mr Flitcroft, Palladian Architect

Postscript

The Rogue Goths: R.L. Roumieu, Joseph Peacock, and Bassett Keeling by Edmund Harris is published by Liverpool University Press.

David Frazer Lewis is Associate Professor of Architectural History and Cultural Heritage at the University of Oxford. He is the author of A.W.N. Pugin.

No comments yet