Vishvesh Prabhakar Kandolkar’s new book examines how colonial power shaped the visual and political representation of Goa’s Basilica of Bom Jesus, revealing the role of photography in framing its legacy. Oriana Fernandez explores how the study sheds new light on the basilica’s evolving cultural identity and the ongoing debates over its conservation

I first encountered the Basilica of Bom Jesus through photographs, as many do. However, Vishvesh Prabhakar Kandolkar’s new book reveals how these images served colonial power – a revelation that transforms our understanding of this UNESCO World Heritage site. Before diving into this study, I recommend readers explore the recent interview conducted by R. Benedito Ferrão with Kandolkar, which charts the basilica’s journey from the pride of the Portuguese to a symbol of Goan cultural identity and heritage.

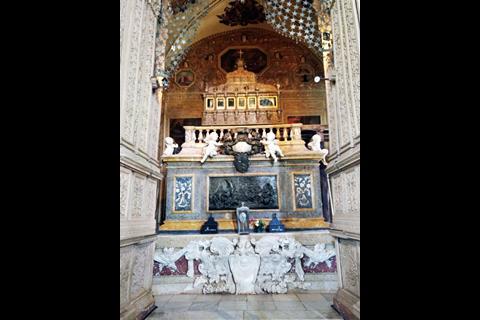

Commissioned by the Jesuits and constructed between 1594 and 1605, the basilica is one of Goa’s most significant colonial-era churches and houses the remains of St Francis Xavier, a key figure in early Jesuit missionary work. Its Baroque architecture, laterite stone construction, and religious importance have made it a focal point of both Goan Catholic devotion and ongoing debates over heritage conservation practices.

The book’s exploration of theoretical foundations in Chapter One illuminates Portuguese colonial power and photography’s role in shaping public perceptions of the building. The author’s own photographic choices intrigue me – the book’s images appear in black and white or sepia tones, mirroring historical exposition souvenirs. This aesthetic choice, whether intentional or practical, enhances the book’s historical depth and reinforces its central themes.

Chapter Two plots Portuguese colonisation’s arc, tracking the rise and fall of Goa Dourada (the “Golden Goa” of the colonial era, once famed for its wealth and grandeur) alongside church-state relations. Here, I noted a missed opportunity – a visual timeline would help readers grasp the complex interplay between Catholic institutions, religious monuments, and Panjim’s emergence as the new capital. This is not typical colonial history; it is about cultural authority expressed through architecture.

The analysis deepens in Chapter Three, comparing exposition souvenirs from 1859 and 1890. These books served as portable pieces of sacred architecture, letting pilgrims possess fragments of the space housing St Francis Xavier’s relics. Kandolkar reveals a telling shift between editions – from the saint’s biography to an architectural celebration. His discovery about officials aligning Xavier’s birth date with Vasco da Gama’s departure for India exposes the calculated manipulation of historical narrative.

Chapter Four’s examination of “negative space” proves revelatory. Early photographers, from British pioneers in 1855 to the Souza & Paul studio after 1884, created carefully framed images isolating the basilica from its surroundings. These were not mere documents but tools of empire, presenting the building as a timeless monument rather than a living structure.

The 1952 exposition, explored in Chapter Five, marked a pivotal shift. Held to commemorate 400 years since the canonisation of St Francis Xavier, the event was part of a long-standing tradition in which the saint’s relics were publicly displayed every ten years. As pressure mounted for Goa’s integration with India, colonial authorities orchestrated an elaborate procession of the relics between the Basilica and Sé Cathedral. Drawing 50,000 attendees, this religious ceremony doubled as political theatre. Kandolkar’s analysis of photographs and films reveals the Portuguese authorities’ final grand assertion of cultural legitimacy through architectural spectacle.

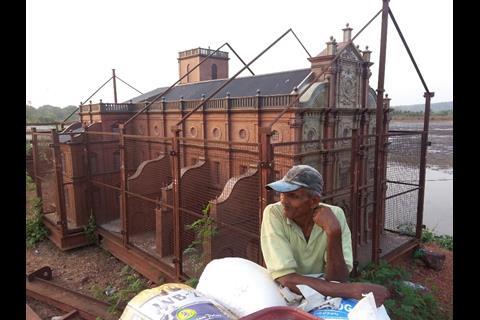

Chapter Six confronts present-day challenges with scholarly precision. Climate change threatens the Basilica’s exposed laterite stone structure, with rainfall increasing by 68% over a century. The removal of protective plaster in the 1950s by the dictatorial Salazar regime left the building vulnerable to intensifying environmental assault. Current debates between the Archaeological Survey of India and the Church about conservation methods – traditional lime mortar versus modern materials, “mud pack” repairs versus complete restoration – reflect deeper questions about cultural ownership and authenticity.

Throughout, Kandolkar weaves voices from various periods into his narrative, reminiscent of Margaret Mascarenhas’ novel Skin in its rich historical storytelling. His research draws on architectural plans, historical documents, photographs, and films while maintaining scholarly rigour. As a Goan academic, he brings a valuable perspective to the study, offering a nuanced understanding of how colonial legacies, local identity, and contemporary heritage debates intersect in shaping cultural memory.

The Basilica’s continued significance (3.2 million visitors in 2014) demonstrates how thoroughly Goans have reclaimed this colonial structure. Kandolkar shows us that architectural history extends beyond style and structure into how societies use buildings to tell stories about themselves. While the text occasionally assumes detailed knowledge that general readers might lack, this rarely impedes understanding.

The Basilica de Bom Jesus belongs to that rare category of buildings that become shorthand for entire cultures and regions. Just as the Taj Mahal symbolises India, the Forbidden City represents China, or Angkor Wat stands for Cambodia, this basilica has become Goa’s architectural signature. Yet unlike these primarily historical monuments, Bom Jesus maintains its original religious function while carrying a broader cultural weight.

Kandolkar’s study helps us understand how certain buildings transcend their original purpose to become cultural anchors. The Basilica de Bom Jesus is not just another Portuguese colonial church – it is a mirror reflecting centuries of Goan history, adaptation, and resilience. In showing us how this transformation happened, Kandolkar offers insights into how architecture shapes identity across cultures and centuries.

As heritage sites worldwide face similar challenges of preservation and meaning, this study offers valuable lessons about architecture’s role in identity formation. Kandolkar maintains respect for the Basilica’s spiritual significance while revealing its broader cultural importance. His thorough analysis will interest architects, historians, conservationists and anyone curious about how buildings shape collective memory.

We see how buildings outlive their builders’ intentions, taking on new significance for each generation. In documenting this architectural edifice, Kandolkar has created an essential text for understanding how buildings shape our sense of who we are, while providing crucial lessons for heritage preservation in an age of climate crisis.

>> Also read: From the Mauryas to the Mughals: ‘A meticulously curated window into the architectural styles of ancient India’

Postscript

Goa’s Bom Jesus as Visual Culture: The Basilica’s Architecture, Image, History and Identity by Vishvesh Prabhakar Kandolkar is published by Routledge.

Oriana Fernandez is an architectural and urban designer, and a mentor on the RIBA’s Future Architects student mentoring scheme

No comments yet