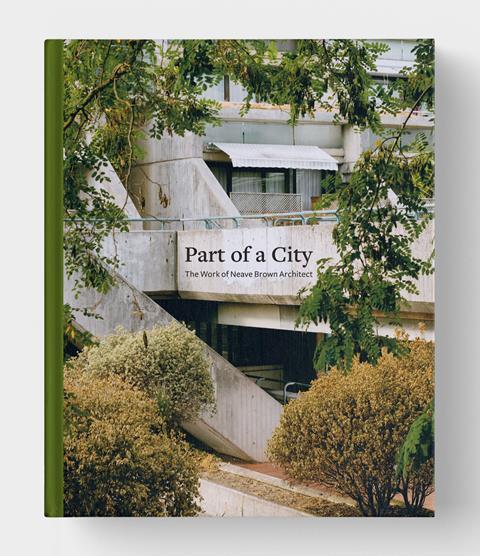

In this edited excerpt from the introduction to a new book on Neave Brown, Patrick Lynch explores the enduring relevance of the architect’s work

Unusually articulate for an architect, Neave Brown wrote well and convincingly about the “dilemma” of making modern architecture in traditional city settings, describing this as “the apparent incompatibility of two systems, each the product of values given priorities at different periods in the same culture, and typified by ‘the street and the façade’, and by ‘the building in context.”

Teaching at Cornell and at Princeton, alongside Colin Rowe, Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman and others, Brown was exposed to his fair share of loudmouths and cranks claiming to have the last word. Yet he continually sought a via media, one which acknowledged the role of modern construction in architectural design, whilst maintaining that what mattered above all else was making “a part of a city”.

In doing so, unusually for a practising architect, Brown admitted to several doubts and “dilemmas”, and even to unresolvable “tensions” in his work. He didn’t believe in an academic architecture that worked best on paper, and instead, he tried to intervene and to “participate in situations in a state of change” (as Alvaro Siza memorably described the primary act of design).

Just as Neave Brown wasn’t looking to have the final word, neither does this book

Dalibor Vesely often remarked upon the fact that whilst teaching at the Architectural Association during the 1970s, he often found himself, literally and figuratively, occupying a narrow and somewhat awkward position in-between Leon Krier and Peter Cook; defending a middle-ground upon which to construe a situated modern architecture, critical of both formalistic traditionalism on the one hand, and technico-instrumentalism on the other. Neave Brown was aware of and cautious of these extremists too, and similarly critical of their absolutist fantasies.

Just as Neave Brown wasn’t looking to have the final word, neither does this book. Instead, we present to you a range of views and a collection of primary sources for further scholarship and for architects to reflect upon. Our hope is that the recent renewal of interest in Brown’s work, and simultaneously in the buildings of George Finch and Kate Mackintosh and others involved in the Welfare State project of Britain in the twentieth century, might be the stirring again of a new-old spirit in architecture – one oriented towards a prudent desire for social justice founded in practical ethics.

Despite its later critical success, and in contrast to the near adulation that Brown’s work has recently received, the initial view of Alexandra Road was not universally positive however, and in fact quite negative. Reyner Banham was extremely critical if not hostile and mocking in his description of the project, claiming that “the late William Howell” had once declared, “when he was working in the old LCC architect’s department: ‘Let’s face it mate, housing is a charity shat upon the working classes from a great height!’”

Banham ridiculed the idea of an architect wishing to control an architectonic environment to the extent that the external planting is regulated by the council gardeners, seeing this as painfully out-dated and even embarrassingly paternalistic. In an otherwise snooty and somewhat catty article about Alexandra Road – he even recounts waspish “cocktail party chat” with Brown - Reyner Banham concluded that “the problem of mass housing remains exactly where it was ten years ago… and will probably still be there in ten years’ time when Neave Brown’s early work will be due for inevitable historical revival as part of some ‘British tradition of large scale planning’.”

Yet Brown was kept busy defending his work and his reputation over the next few years, writing a letter of defence to the RIBA Journal in September 1980 following another extremely hostile review of Alexandra Road that June, and dealing with Camden Council’s own lawyers.

Margaret Thatcher’s first government, elected in 1979, made it illegal for local authorities to borrow money to build housing, effectively ending the socially progressive policies of local architects’ departments across the UK, and with this the careers of most of the architectural profession employed at that point in local government. Some departments limped on, gamely focussing on school projects, e.g. Kate Mackintosh moved from working on housing projects for London councils to Hampshire County Council Architect’s Department to work on a number of award-winning schools, but Brown’s career as a housing architect in the UK was effectively over.

Only in the past 15 years or so, have London borough councils, such as Camden and Hackney, sought once again to develop mass housing projects in London

Banham’s prediction, like a lot of his presumed clairvoyance, was tragically wrong: we did not continue to debate the problem of mass housing design in the UK – instead the debate was supposedly won by the economic success of the plethora of semi-detached houses in cul-de-sacs that comprise most of the housing stock built in Britain since the 1980s. In some senses Brown did have the final word though, even if it was the last thing he imagined Alexandra Road being.

Only in the past 15 years or so, have London borough councils, such as Camden and Hackney, sought once again to develop mass housing projects in London. What has been lost in the intervening decades cannot be exaggerated though and includes the relationships that Brown and other Camden architects and planners investigated concerning the presence of cars in cities, and in particular the character of the architectonic or civic ground.

Unlike most British architects, who tend to study Mathematics and Art, often with another science subject (usually Physics), Brown had studied English A Level at his public school, Marlborough College. To his father’s bemusement and irritation, Brown had in fact turned down a scholarship to study English at Oxford in favour of the Architectural Association. However, whilst this partly explains his capacity to treat the polemical canonical texts of modernist dogma with careful critical scrutiny and also some irreverence, rather than the usual cultic devotional fervour of the recently initiated, his cultural observations and insights are also profoundly psychological and anthropological.

In contrast to the dogma of British Hi-Tech architects and the polemics of Archigram, Brown is critical of the “disastrous” aspects of modern architecture

Rather than accepting blindly modernist dogma, he is gracious enough to acknowledge that whilst the “actual achievements were real enough and still move us by their authority”, unlike many modern architects who worshipped at the altar of technological progress, he also describes the “gigantic horror of the industrial revolution” as inspirational for “the modern movement, both its everyday values and its utopias.” In contrast to the dogma of British Hi-Tech architects and the polemics of Archigram, Brown is critical of the “disastrous” aspects of modern architecture, and subtle enough to critically accept the cultural values of traditional architectural settings for their urbane power and civic dimension.

Which is why, I believe, that rather than thinking of housing as a technical or sociological problem, he conceived his task as an architect as the fabrication of “part of a city”. In doing so, he was able to acknowledge the “older, revalued culture represented by the continuing city”: even if, and perhaps especially so, this entailed recognising that he contributed to this continuity “with varying degrees of success”.

Displaying both empathy and situational intelligence, curiosity and courage, and a degree of spiritual calm, patience, hope and tenacity, Neave Brown’s example of “authentic” praxis is something that we have a lot to learn from today, not only as designers and writers, but also as citizens.

This book is not a hagiography though; it is not an attempt to pretend that the tragedies and successes of Brown’s career are not the fruit of profound political and social changes that we are still living through. Part of a City presents to the reader Brown’s own efforts in an open-minded manner we hope, and yet inevitably in a partisan manner; because we think, as architects and critics, that we have so much to learn from him, both as a person and as an architectural thinker revealed in both his writing and built work.

Our hope is that this book, along with its siblings, might help us all to become better students of architecture.

Also read>> Part of a City: The Work of Neave Brown Architect

Postscript

Part of a City: The Work of Neave Brown Architect is published by Canalside Press.

Patrick Lynch is director of Lynch Architects and publishing editor of Canalside Press.

No comments yet