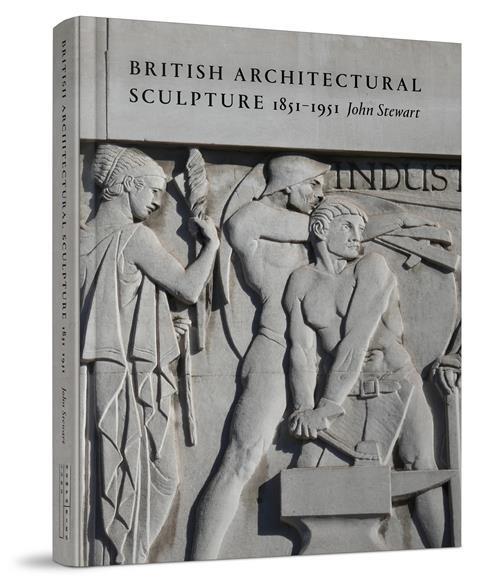

Timothy Brittain-Catlin reviews John Stewart’s exploration of architectural sculpture, charting its evolution from the 1850s to the 1950s

You have to go back a very long time, perhaps to H. S. Goodhart-Rendel, to find a writer on architectural history who was themselves a distinguished designer. And even he would never have been capable of producing so perceptive, so clever, so enjoyable a book as John Stewart’s Architect to the British Empire, his uninhibited biography of Herbert Baker, which appeared in 2021. The author, responsible for several first-rate buildings as deputy county architect in Buckinghamshire, liberally praised by the authors of the Pevsner guide, has now turned his attention to the subject of architectural sculpture between the eras of the Crystal Palace and the Festival of Britain.

The common theme across the period is that sculpture itself could be part of the fabric of the buildings rather than something added on. The Edwardian architect Edwin Rickards once wrote that the practice of placing a portrait sculpture on a free-standing plinth in or by a building reminded him of the school dunce (perhaps himself) being made to stand on a stool in the middle of the classroom. So for him in particular, and for the best of the architects fifty years either side of his brief career, the key to great design was the thorough amalgamation of the artistry of the sculptor and architect to the extent that it was not possible to work out where one ended and the other began.

Furthermore, the nineteenth century saw the flowering of the New Sculpture movement, the move away from the stiff formality of classically inspired figures that in mid-Victorian England was rapidly approaching the kitsch, if not the near-pornographic, towards writhing forms that looked sometimes as if they were struggling with inner emotions.

The pioneer was Alfred Stevens, creator of the carvings on the Wellington monument in St Paul’s Cathedral in London; Henry C. Fehr, whose The Rescue of Andromeda sits outside Tate Britain, is another prominent figure. Theirs are works which do not need an architect to attain their full power, but where sculpture and building come together, the results can be astonishingly powerful.

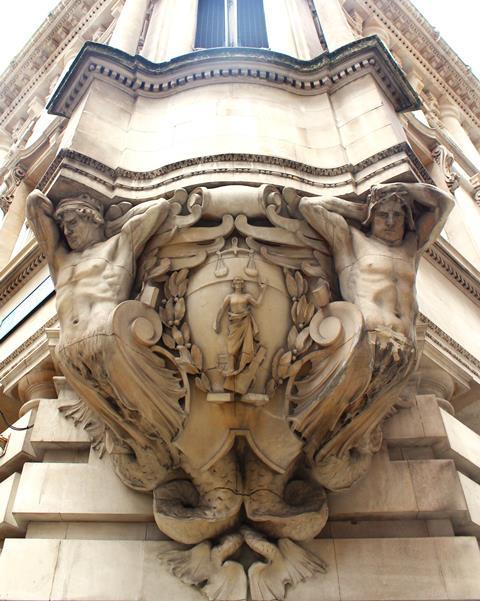

There is a great deal of this type of work, and sometimes it is responsible for the overall character of buildings with which many people are familiar; and it often happened that more than one of these great architectural sculptors collaborated on a single building. As Stewart points out, perhaps the most influential was John Belcher and A. Beresford Pite’s Chartered Accountants’ Hall in the City of London (1888–1893), where Hamo Thornycroft devised an astonishing frieze of characters along the full length of the building’s two facades, and Harry Bates added a pair of atlantes and a row of curious sci-fi caryatids, the whole composition marking the return of the baroque to Britain but now with an almost secessionist edge.

Most, but not all, of the key buildings described by Stewart are classical: Bates also worked with W. S. Frith on the gothic Victoria Law Courts in Birmingham, a kind of stupendously ornate sandcastle. Anyone looking up carefully at the former War Office building in Whitehall will find a shockingly powerful set of figures, depicting, for example, ‘The Horror of War’, by Alfred Drury.

The story of integral sculpture continues well into the twentieth century, and the later chapters illustrate work by Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henry Moore but also by naturalist sculptors such as Charles Wheeler, Alexander Carrick and Gilbert Bayes, whose panels on James Miller’s Commercial Bank in Glasgow of 1934 are a delight. This is an inspiring and valuable book, and I for one am recommending it strongly to our students and apprentices.

> Also read: Is the lack of ornament in architecture a barrier to diversity?

Postscript

British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951 by John Stewart is published by Lund Humphries.

Timothy Brittain-Catlin is an architect and architectural historian. He is professor of architecture and course leader on the MSt Architecture Apprenticeship programme at the University of Cambridge. He is the author of several books, including The English Parsonage in the Early Nineteenth Century and Edwin Rickards.

1 Readers' comment