Stardust, a film by Jim Venturi and Anita Naughton, offers an intimate portrait of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, shedding light on their creative partnership and radical ideas. Oriana Fernandez explores how the film reveals the human story behind two of architecture’s most influential figures – and what their work still has to teach us today

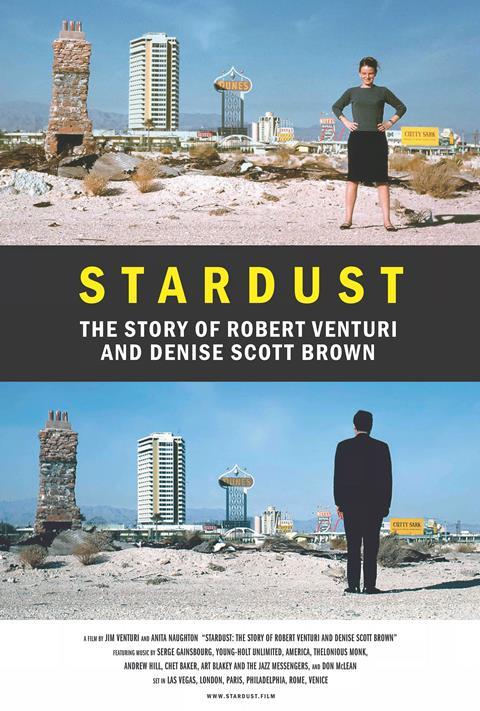

Jim Venturi and Anita Naughton’s film Stardust: The Story of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown paints an intimate portrait of architecture’s most influential partnership, revealing the human story behind revolutionary ideas. Screened at the Barbican late last year, the film captures Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s rebellious spirit, creative synergy, and their fight for recognition in a profession that often sidelined women. Personal reflections connect their theoretical work to their lived experience, bringing new depth to ideas that continue to shape architectural discourse.

The Barbican’s screening of Stardust transported me back to my fourth year at the Goa College of Architecture, where I first encountered Venturi and Scott Brown’s revolutionary ideas in Dr. Vishvesh Kandolkar’s Urban Design Studio. Now, watching their story unfold on screen, I saw the human dimension behind the texts that had shaped my architectural education.

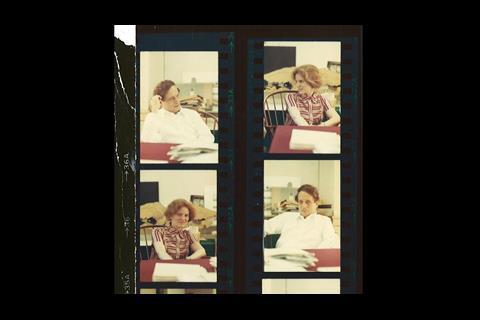

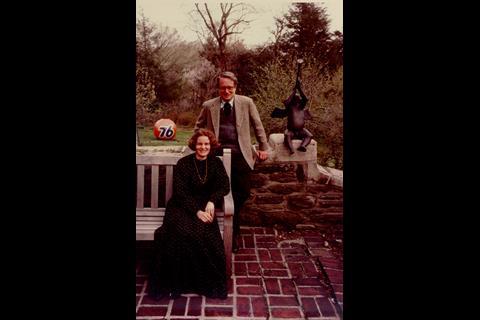

Twenty years in the making, this film – directed by the couple’s son, Jim Venturi, alongside co-director Anita Naughton – paints an intimate portrait that transcends architectural biography to explore the intersection of love, creativity, and professional recognition. The 90-minute film follows Bob and Denise revisiting sites that defined their careers, reflecting with the emotional candour that comes only with the passage of time.

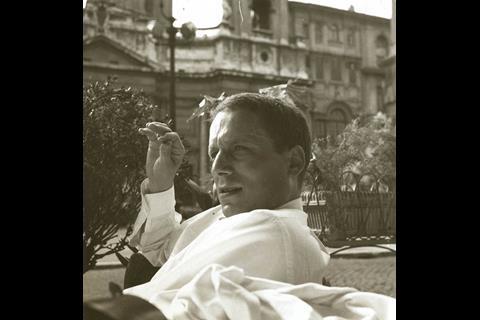

The contrasting personalities of the pair leap off the screen. Venturi possessed an almost monk-like devotion to his craft – working every day, quietly dedicated to drawing and thinking simultaneously. As his son Jim describes, “Bob is someone that if he would go to a gas station would have no idea how to pump the gas… he was deeply imbalanced as a person, he had this incredible genius and that’s all he knew.” This devotion to art manifested in his discomfort with being labelled an intellectual: “I’m an artist who thinks a lot,” he insists in footage from a Columbia University talk.

The film particularly shines when exploring their revolutionary Las Vegas research

Scott Brown emerges as the more vocal, analytical half of the partnership – bringing fresh eyes and urban planning theory to their practice. Their complementary qualities created what architectural historian Vincent Scully describes as “a gentility, a softness, a sweetness that does not go very often with a large talent.”

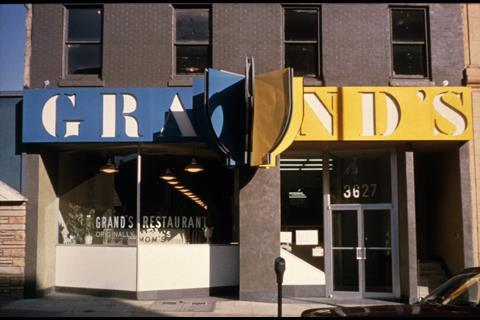

The film particularly shines when exploring their revolutionary Las Vegas research. Footage shows the pair walking through casino parking lots in their later years, recalling their 1968 Yale studio trip. When confronted by a critic’s horror at comparing “crappy signs” to classical architecture, Venturi’s quick-witted response cuts to the heart of their thinking: “Would you rather be sold religion or soap on a billboard?”

This questioning of architectural hierarchies – which had seemed so academic when I first studied it – takes on new meaning when you see the rebellious spirit behind it. The film shows their Chestnut Hill home, where Venturi painted the exterior green specifically because Walter Gropius said green should never be used outdoors in architecture.

The film does not shy away from addressing the gender inequity that has shadowed their legacy, particularly the 1991 Pritzker Prize controversy. “They decided Bob wrote my article and was using me as a stalking horse,” Scott Brown recalls, describing how their joint work was systematically attributed solely to her husband. As a woman in architectural practice, this section resonated painfully with me.

The Sainsbury Wing at London’s National Gallery is their most public triumph. We learn Bob sketched initial ideas on an airplane menu, creating a building where viewers can see “the real world and a Raphael almost at the same time.” The British architectural establishment’s initial resistance to the design feels all too familiar.

The post-screening Q&A with Jim Venturi and Naughton revealed the challenges of crafting a dual narrative. “One of the things we were told was you can’t have a film with two main characters,” Venturi explained, which led to their decision to create two subsequent documentaries – one focused on each architect.

Co-director Anita Naughton, who came to the project with no formal architectural background, offered insights during the Q&A about how she approached the material. “I didn’t really know anything about architecture, so it was a real learning experience,” she admitted. Her editorial approach was guided by what she called “the principle of aliveness” – focusing on moments that resonated emotionally rather than trying to create a comprehensive architectural survey.

Their combined vision was not just about academic theory, but about two people who, as Scott Brown puts it, had “this strange feeling that you can do right, do good, and also design well”

“I took what struck me when I watched the footage… what revelations I had about architecture, not knowing anything,” Naughton explained. This fresh perspective helped strip away academic pretensions to reveal the human story at the core of the Venturis’ work. “Because it’s two people, and they’re both brilliant, there’s so much I had to leave out. I had to always keep a balance between the two.”

Moderator Ellis Woodman found himself briefly interviewed by Jim, who asked how he first discovered the duo’s work. Woodman’s enthusiastic recollection of discovering Complexity and Contradiction as a teenager in Scotland mirrored my own experience of finding their writings during my architectural education.

Now, years after first studying Learning from Las Vegas in Dr. Kandolkar’s course, seeing the human story behind these theoretical giants brought their work into sharper focus. Their combined vision was not just about academic theory, but about two people who, as Scott Brown puts it, had “this strange feeling that you can do right, do good, and also design well.”

The film reminds us that architecture is never only about buildings and their users – it is also about the complex, contradictory humans who make them. As architects, we should not be ashamed of this – in fact, we should feel compelled to reflect more on our role in the design process. As I watched Jim Venturi’s loving portrayal of his parents, I realised how much their willingness to find meaning in overlooked places had influenced my own architectural thinking.

>> Also read: Building study: Learning from Denise Scott Brown

>> Also read: Denise Scott Brown rips into Selldorf’s National Gallery plans

Postscript

Oriana Fernandez is an architectural and urban designer, and a mentor on the RIBA’s Future Architects student mentoring scheme.

Jim Venturi and Anita Naughton are planning further screenings of the film in London in the near future. Further information can be found on Instagram.

No comments yet