Wakefield’s Tileyard North is the latest attempt to harness the creative economy as a driver of regeneration, transforming the long-derelict Rutland Mills into a major cultural hub. More than two decades after Richard Florida championed the creative class as a catalyst for urban renewal – and amid ongoing debates about gentrification – the project suggests creative reuse can still be a means of reviving post-industrial cities

For decades, the Rutland Mills complex in Wakefield stood as a derelict relic of the city’s industrial past – its red-brick warehouses, once central to the wool trade, slowly falling into decay. Now, after a £40m-plus transformation, the site has been reborn as Tileyard North, a creative industries hub intended to be the largest of its kind outside London.

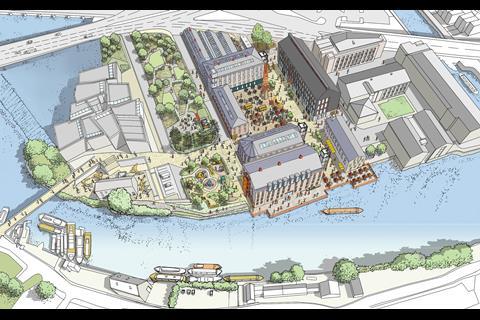

Developed by City & Provincial Properties, in collaboration with architects Hawkins\Brown, the project is an ambitious northern counterpart to Tileyard London, City & Provincial’s music and media campus near King’s Cross. Located beside David Chipperfield’s The Hepworth Wakefield, Tileyard North is a key part of the West Yorkshire city’s wider regeneration strategy, reactivating the waterfront and providing workspace, recording studios and event spaces designed to foster a creative community.

Yet, this transformation was far from straightforward. As architect Nicholas Birchall of Hawkins\Brown explains: “The site had been abandoned for over 50 years – many of the buildings were structurally unsound, some had lost their roofs entirely. The challenge was how to bring them back to life while keeping their industrial character intact.”

When Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class was published in 2002, it had a profound influence on urbanism and urban regeneration, shaping policies that prioritised attracting creative professionals as a strategy for economic growth. His argument – that cities could thrive by fostering vibrant cultural and creative hubs – was embraced by policymakers and planners worldwide. However, his ideas came in for increasing criticism for their role in fuelling gentrification, pushing up property prices and exacerbating social inequalities.

Today, as the UK’s economic health deteriorates – with the economy flatlining and many towns and cities visibly struggling – the debate around Florida’s thesis takes on a different tone. In places such as Wakefield, where large-scale regeneration projects like Tileyard North aim to spark new creative economies, the question is not whether gentrification is a threat, but whether a degree of it might now be very welcome indeed.

Origins of Tileyard North

The site has a long industrial history, first serving as 19th-century grain warehouses before being redeveloped into a wool-spinning mill in the 1870s. For nearly a century, the red-brick buildings housed large-scale textile production but, by the 1970s, operations had ceased.

The transformation began when one of the directors of City & Provincial visited The Hepworth Wakefield and recognised the neighbouring site’s potential. “They saw what a fantastic collection of buildings this was,” says Birchall, recalling how Hawkins\Brown was appointed in 2016 to masterplan the site’s revival.

For City & Provincial, Tileyard North was the culmination of a long search for a northern counterpart to its successful London music-industry campus. “We had been looking for a while,” explains Louisa Brooks, asset manager at City & Provincial.

“We explored opportunities in Manchester and Liverpool, but Wakefield stood out because of its existing creative context – being next to The Hepworth made it a natural fit.”

Proximity to Leeds’ established media and music clusters was also a draw, as was the site’s transport connectivity. “Wakefield is only two hours from King’s Cross, and a lot of our occupiers use both facilities. So everything just came together for it,” Brooks adds.

Yet, while the location was promising, the site’s condition presented major challenges, with many buildings suffering extensive structural deterioration. “It was really, really dilapidated – completely unsafe,” says Brooks.

“There was a real mix of conditions,” Birchall explains. “Some buildings were relatively intact, others were near derelict.”

The masterplan had to balance conservation with practicality, ensuring that the site could be adapted for modern use while retaining its industrial character.

The challenge was not just architectural, but urban: reconnecting the long-neglected mill complex to the waterfront and The Hepworth while preserving its industrial character. “The buildings had been closed off to the public for a long time, and many were structurally unsound, some missing entire roofs,” Birchall explains.

For City & Provincial, the sheer unpredictability of the site’s condition was one of the biggest obstacles. “However many surveys we had prior to starting the work, you never know what you’re going to find,” says Louisa Brooks, development director at City & Provincial.

“That was probably where we faced the biggest challenges – dealing with the unexpected structural issues as we went along.”

Despite these hurdles, the approach was always to retain as much of the historic fabric as possible, while making necessary interventions to ensure long-term viability.

Infrastructure and funding

Critical to the masterplan was securing public funding to support heritage conservation and infrastructure upgrades. Wakefield council played a key role, alongside support from Historic England and levelling up funding.

“The funding came from a mix of sources,” says Birchall. “It wasn’t a single pot of money but different grants aligned to heritage and regeneration.”

For City & Provincial, working with the council from the outset was essential. “We worked closely with Wakefield council, not just on the purchase, but also to ensure we had the planning permission we needed before acquisition,” says Brooks. “That gave us the certainty to move forward with confidence.”

Flood defences were another essential element, with improvements made to protect the site from the River Calder while enhancing its relationship with the water. “It was about futureproofing,” Birchall notes. “Making sure these buildings are not just restored, but resilient.”

Stitching old and new

Progress paused in 2017 as the developers sought a joint venture partner and more funding streams. But, by 2019, with support from the council, Historic England and those levelling up funds, the first four buildings were earmarked for restoration.

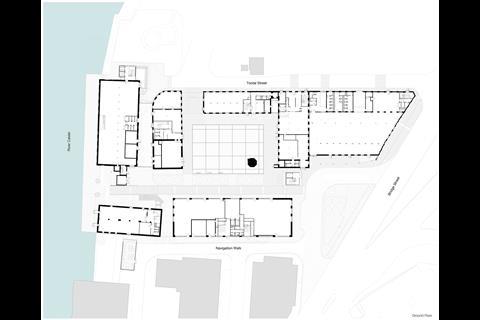

Given the project’s complexity, it was divided into phases to ensure financial and logistical viability. Phase 1 focused on stabilising four existing buildings: Cutter Mill, Cotton Mill, Corn Mill and the Carding Shed. Their brickwork, roof structures and original openings were restored, while a new office building was introduced to complete the fourth side of a central courtyard, alongside enhancements to the public realm.

Phase 2, which is currently underway, will introduce a hotel adjacent to the river and see the conversion of the oldest building on the site into new grade A workspace. Also approaching completion – but not yet open – is a riverside boardwalk, strengthening connections to the waterfront and The Hepworth Wakefield.

“It’s about stitching the site back together,” Birchall explains. “Reactivating these buildings in a way that respects their heritage but makes them functional again.”

Brooks echoes this sentiment, emphasising that the success of the scheme so far has been in how the new and old elements have come together. “We always envisioned a large courtyard at the centre, but the challenge was making sure the fourth building tied in seamlessly,” she says. “It really completes the project.”

One of the biggest challenges was how to introduce modern access – such as new circulation cores and accessibility upgrades – without compromising the integrity of the original structures. “Where possible, we kept interventions external,” says Birchall, explaining the decision to place new stair cores outside the buildings rather than cutting into historic fabric.

The masterplan embraces a “light-touch” conservation approach, where new additions are visually distinct from the original structures. “You can see what’s old and what’s new,” Birchall explains, “but it all still feels part of the same story.”

The Tileyard North masterplan prioritised adaptive reuse, with over 80% of the original fabric retained. However, the extent of structural deterioration varied across the site. The approach combined conservation and contemporary interventions, with new slate roofing introduced where original materials could not be salvaged.

“We salvaged what we could and then paired it with new slate,” says Birchall. “You read the roofscape as part old, part new, but geologically the same.”

Material and spatial strategy

Rather than altering the grade II-listed interiors, new steel-framed stair cores were placed externally, reducing the need for invasive structural changes. “Anywhere we had to rebuild, we used a different bond pattern so the additions remain legible,” Birchall explains, describing the stack-bonded infill approach used to distinguish contemporary interventions.

One of the most significant spatial moves has been the creation of the central courtyard, replacing lower-grade infill buildings that had accumulated over time. This open space not only provides a breakout area for Tileyard’s creative community but also serves as an event space, reinforcing the site’s function as a social and cultural hub.

Around this courtyard, a variety of workspaces were introduced, designed to accommodate different creative disciplines – from single-person studios to larger co-working set-ups, ensuring flexibility in how the space is used.

Elsewhere on the site, key historic features have been carefully reinterpreted. The mill chimney, which had been partially demolished for safety reasons, was a defining element of the original complex. It has now been reinstated as a lightweight steel structure and is illuminated at night, acting as a visual marker within the city.

At roof level, the poor condition of the existing structures presented another challenge. The solution in the events space was to introduce lightweight polycarbonate roof lights along the north-facing pitches, allowing for diffused natural light and improved ventilation.

“The idea was to reintroduce the roof in a way that wouldn’t replicate the structural challenges it had before,” Birchall notes. “It was about keeping the site’s DNA intact but making it work for today.”

The final part of phase 1, a new five-storey red-brick office building, picks up on the industrial character of the site, with a familiar but effective architectural language. Large glazing units recede in height as the building rises, implying a hierarchy of space, and also responding to the changing light conditions higher up the building. The spacious top floor is open to the underside of the steel truss roof, echoing the architecture of the adjacent former mill buildings.

A creative hub for music and media

Tileyard North has been designed as a specialist hub for the creative industries, with a strong focus on music production, content creation and flexible workspaces. At the heart of the development is Cotton Mill, which houses 27 purpose-built recording studios.

“There are some studios taken on private leases by recording artists, and a record label occupies the entire top floor,” explains Birchall as he take BD on a tour of the site. Facilities include shared access to recording studios, podcast suites and a photography studio, allowing members to rent spaces on an hourly basis.

The broad mix of occupiers reflects Tileyard London’s established model, where a concentration of music professionals, content creators and associated businesses co-locate in a single creative ecosystem. “At Tileyard London, we started with 10 music recording studios, and that has grown to over 150,” says Brooks.

Adjacent buildings accommodate small-scale creative workspaces tailored for music producers, content creators and digital agencies. “It’s been interesting to see the mix that’s settled here,” says Birchall. “There’s a strong concentration of producers and content creators who need both individual space and access to shared facilities.”

Leisure and public realm

Tileyard North is more than just a workspace – it is intended to function as a social and cultural hub. The ground floor features a café and gin distillery, with the latter bringing a small-scale industrial process back to the site. “They are actually distilling on site, which really ties into the historic industrial character of the mill complex,” Birchall notes.

The development also includes two event spaces designed for concerts, weddings and corporate gatherings. The larger venue has a maximum capacity of 800 people, while the smaller first-floor space is primarily used for weddings and conferences.

“There was a lot of discussion about whether we should have a dedicated music venue,” Birchall explains, “but we ultimately opted for flexibility—pop-up stages rather than a fixed performance space, so it can adapt over time.”

Brooks highlights the importance of the event spaces in shaping Tileyard North’s identity. “The indoor events spaces are beautiful,” she says. “We’ve worked closely with The Hepworth Wakefield on various events and the synergy between the two sites has been really important. They use our space for some of their programming and, in turn, our tenants benefit from their gardens and cultural events.”

Outdoor events are also a key part of the vision. The central courtyard has been designed to host pop-up performances, markets and festivals. “This weekend, they’re setting up a food and music festival,” Birchall says, pointing out the infrastructure designed to support events. “The courtyard ties everything together and creates a space that people can use in lots of different ways.”

The flexible nature of the space allows Tileyard North to complement the programming at The Hepworth Wakefield, helping to extend the cultural reach of the waterfront beyond the gallery itself. Perhaps one weaker point is that Hawkins\Brown largely seems to have missed the opportunitty to engage more directly with the gardens, designed by Tom Stuart-Smith, that lie between Tileyard North and the gallery.

Relationship with The Hepworth Wakefield

Though Wakefield was not previously known as a music industry hub, the developers saw potential in its strong transport links and a council committed to cultural regeneration. “Wakefield has been really progressive in how it sees culture and heritage as key drivers for regeneration,” Birchall explains.

“The music industry followed the opportunity here, rather than the other way around,” he adds, pointing to the new jobs and businesses that have already been drawn to the site. The presence of record labels, production studios and content creators is reshaping the local economy, offering opportunities for both established professionals and emerging talent.

Tileyard North and The Hepworth Wakefield sit side by side, yet they could hardly be more different in form and materiality. The Hepworth is a monolithic, sculptural presence in smooth concrete, a stark contrast to the rugged industrial buildings of Tileyard North.

Birchall regards this contrast as an asset: “We see this as being in some ways a really positive counterpoint. The Hepworth has soft landscaping, while we have hard landscaping. Their spaces are beautifully curated, whereas ours are more tactile and adaptable.”

This distinction allows for complementary uses, giving the two sites a distinct but symbiotic identity.

Tileyard North sits slightly outside Wakefield’s town centre, but its location is key to its success. It benefits from close proximity to Wakefield Kirkgate station. There is also a shared ambition to extend the city’s cultural offer beyond The Hepworth itself, drawing visitors deeper into the city.

As Birchall puts it: “Since The Hepworth was completed, there has been a bit of a stalling in terms of wider regeneration. This was quite a big block along the waterfront, so a major part of the project has been about opening it up and creating better connections through Wakefield.”

The future

With phase 2 set to deliver a hotel, more workspace and a new riverfront pier, the site is evolving into a fully integrated part of Wakefield’s waterfront regeneration. A key challenge will be ensuring long-term sustainability.

Birchall acknowledges that, while Tileyard North is already thriving, it must continue to embed itself in the wider economy. “This project has been transformational for the waterfront, but it’s also about making sure it draws a consistent crowd beyond just events.”

With expansion plans already in discussion – including the potential acquisition of neighbouring buildings – Tileyard North is positioning itself as a long-term driver of the city’s cultural and economic future. It is more than a creative hub; it is a model for adaptive reuse, demonstrating how industrial heritage can be reimagined to serve contemporary cultural and economic needs.

By balancing heritage conservation with modern interventions, the project has retained four-fifths of its original fabric while introducing new infrastructure that supports the music, media and creative industries. It also represents a shift in Wakefield’s regeneration strategy, seeking to embed a long-term creative economy within a key growth area for the city.

The question now is whether Tileyard North can actually serve as a catalyst for that broader regeneration. If it succeeds, it will reinforce the idea that post-industrial cities can still look to the creative industries as a key part of their economic future – not by erasing their past, but by adapting it to new possibilities.

More than two decades after Florida’s publication, the debate over its impact continues. While critics argue that creative-led regeneration fuels gentrification, Wakefield’s approach suggests a more balanced model, leveraging cultural investment as a means to revitalise rather than displace.

At a time when many towns and cities are struggling, and economic stagnation has left places searching for new sources of growth, projects such as Tileyard North raise an important question: can creative hubs serve as a viable regeneration strategy? In Wakefield, at least, the bet has been placed.

>> Also read: Hepworth Wakefield, by David Chipperfield Architects

Project team

Developer City & Provincial Properties

Architect Hawkins\Brown

Structures, civils and highways Civic Engineers

Quantity surveyor Dries & Sommer

Planning CMA Planning

Project managers Opera

Heritage Turley

M&E TB&A

Landscape Reform Landscape Architecture

Principal designers Vey Associates

Fire engineer OFR

Contractors Sewell Construction, Morgan Sindall, Stainforth Construction, Henley Restoration and Remedials, Aura, Harrogate Steel, Stockton Drilling

No comments yet