An Essex barn is given a remarkable new lease of life, by reinforcing its relationship with craft and landscape, writes Ben Flatman

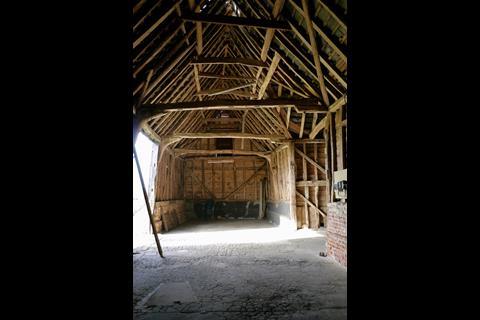

One of the sad ironies of many barn conversions is that, while they might save the fabric, the true inner beauty of these buildings very often ends up hidden behind mezzanines and plasterboard. In the transition from agricultural to residential, the interior spatial qualities and materiality of the barn are too frequently sacrificed due to the desire for subdivision and perceived need to meet conventional expectations of domesticity.

It is therefore heartening to find that Lynch Architects’ recent Jankes Barn project, respects the integrity of the 18th-century structure at its core, while approaching its transformation into a dwelling with a robust clarity. “We like to call it a ‘barn non-conversion’,” says Patrick Lynch, practice director. “The idea was that the best way to inhabit the barn would be to make it feel as little like a conventional house as possible.”

Jankes Barn is located in a hamlet close to the village of Wakes Colne about 10 miles north-west of Colchester. It sits not far from a well-used country lane but, to arrive by car, a visitor would miss a crucial aspect of the design. Instead, approaching by foot from the nearby station, via a path that weaves through wooded thickets and across the flattish open fields of north Essex, helps to underline the significance of landscape to this project.

Landscape

“The garden was central from the start,” says Lynch, explaining how garden designer Joanne Bernstein acted as both client and co-designer throughout the project. For both Lynch and Bernstein, the Essex countryside is not some neutral backdrop, but rather a complex, sometimes strange, presence that required careful and respectful interaction.

To the south, the site extends 23m beyond the house, merging imperceptibly into the surrounding fields, with only a simple, square, reflecting pool and perennial meadow mediating between barn and farmland. Although it lacks the openness of East Anglia proper, the landscape shares some of the same liminal qualities.

To the north, an enclosed courtyard garden with a large planting bed at its centre provides a place of quiet sanctuary. The two very different garden spaces offer contrasting opportunities for both expansive and more introverted contemplation of nature and the surroundings.

Although she retains her home in Tufnell Park, for Bernstein – a life-long Londoner – this move to the country was a long-cherished but sometimes challenging process. She speaks of her own Polish-Jewish heritage, and her sense of trepidation in stepping into the English countryside – a place at once familiar from literature and art, and yet to her still unknown and other.

For Bernstein, with a background in exhibition curation and research, the barn, with its history and rootedness, provided a vital way into understanding the context. “It gives me a way into the landscape,” she says. “Otherwise, I would not have had any entry point with my background.”

“The view is such an integral part of the building,” explains Bernstein. “You can’t separate the one from the other. You feel planted here and it triggered a new interest in farming for me.”

Lynch Architects also worked closely with Bernstein on the design of the new brick benches and patios, fusing their respective roles as architect and landscape designer.

The search for a project

Bernstein had been looking for a house in the area for some time before the barn became available. “I spent lots of time looking at various bungalows and disused barns, and getting out-bid at auctions,” she explains. After finally deciding to buy the dilapidated barn in 2018, she started undertaking her own research into its history and the opportunities that it might present.

One of Lynch Architects’ first projects was Marsh View House in Norfolk, which explored several themes around the role of landscape and the historic villa as a place of regeneration and contemplation.

“We designed various schemes for Jo before starting work on the barn,” explains Lynch. “For example, when she was looking at buying a bungalow, we designed a new building to replace it, and looked at adopting a similar approach to Marsh View - ie part-demolition with major extensions.

“But the barn was the final choice, because fundamentally what Jo was looking to create was a garden, and the buildings were always going to be subordinate to the landscape design.

“Jankes Barn suited this ambition as it always had two archetypal garden spaces – a farmyard that one could also describe as a courtyard,” says Lynch, “and a field that could become something slightly more cultivated.”

The barn was constructed in the late 1780s, but the frame was partly built using reclaimed timbers from even older buildings, some of which date back to the 15th century.

“Jo wanted to do a project and she really drove it,” explains Lynch. There had been a previous planning approval for the barn that had proposed a mezzanine and four bedrooms, but she knew that this familiar “barn-conversion” approach was not the one she wanted to take.

Having read his chapter in the Essex Pevsner, Bernstein spotted that David Andrews, a renowned conservation specialist, was giving a lecture at the nearby Cressing Temple Barns, two remarkable 13th-century survivors from a larger farmstead built by the Knights Templar. A co-speaker was Joseph Bispham, another conservation specialist with extensive experience of timber restoration.

Bernstein introduced herself to them both. “Meeting Joseph and David was a major element in moving the project forward,” says Lynch. “Jo really picked their brains.”

Conservation and construction

A new, listed building and planning application had to be submitted, leading to several listed building planning conditions. Project architect Rachel Elliott takes up the story:

“I think we were probably a little bit naive in that we accepted the initial survey, which said it was in good condition. It wasn’t until we got on site that we realised it was quite a lot worse than we had been told.”

The discovery that much of the timber was in very poor condition meant that the building ended up requiring a large amount of repair work.

“Joseph is quite a remarkable character, with this combination of hands-on knowledge of traditional timber joints and a PhD in historic buildings conservation. He said he could do the timber repairs himself but not the new build works.”

The decision was made to go for a two-stage contract. Bernstein employed Bispham directly, plus scaffolders and underpinners. Where necessary, Bispham replaced timber like for like.

“Then we could begin the process of turning it into a home,” says Elliott. “And having the really specialist work done by Joseph first meant that we could then go out to a much wider range of contractors for the second stage of the contract.”

We were all agreed that the aspiration was to retain the character of the barn as it was

Bernstein ended up appointing John W Younger Ltd, a local contractor with many years’ experience working with listed buildings, to undertake the traditional detailing, including the slate roof and lime pointing, as well as the interiors.

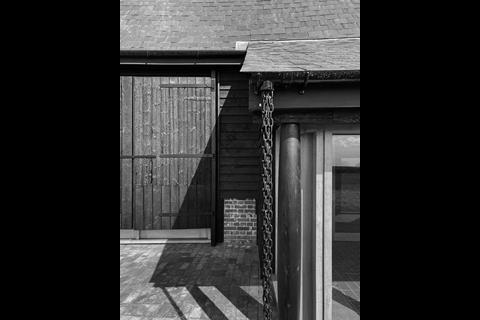

“We were all agreed that the aspiration was to retain the character of the barn as it was,” says Elliott. “Because of the condition of the weather boarding, we couldn’t save any of it. So that gave us the opportunity to really beef up the insulation externally.

“There were quite onerous listed building constraints,” she adds. “Addressing the thermal performance and how this would impact the exterior was a key concern.

“We worked with Max Fordham to develop a green energy strategy, which includes underfloor heating.”

“With the brick plinth, we retained the existing wall and then built a new brick lining internally to match the existing, which is also heavily insulated,” she explains. U values for the completed project exceed the Part L regs for work to an existing dwelling.

The barn as dwelling

The complexities of a heritage and conservation context at Jankes Barn have required Lynch Architects to collaborate closely with a much larger team than previously, as well as with a client who is themselves a talented designer.

“The villa throughout history has been a place where you replenish yourself and return to the land,” explains Lynch. “This is a place where you garden, design and make.”

The design approach is characteristically clear, seeking to draw out the inherent qualities of the barn with a series of sensitive interventions that work with the context and fabric of the barn.

The central barn itself forms the main living space at the heart of the house, with the lower-height wings forming a south-facing sunroom and two bedrooms to the north. The bedroom interiors are lined with plywood, with pods that incorporate bathrooms and storage.

An existing former stable on the northern side of the courtyard garden has become a self-contained guest suite and potential holiday let.

The main living space is articulated by an Antonio Citterio-designed Shaker Stove at the west end, a dining space at the centre and an island kitchen and raised study area at the east end.

The study area is a plywood structure, conceived as a freestanding aedicula within the barn. It has been deliberately placed askew within the plan, aligned with the lane outside, and the former piggery and stable on the other side of the courtyard garden.

I love how the barn looks when the light goes. The whole atmosphere changes

Conceptually, the stable, the piggery and threshing barn have been treated as three parts of a whole, in that they are not the same size or height, yet they are materially very similar and bound together by brick walls that wrap up the courtyard, creating a strong sense of place.

Placing the three new black objects within the barn – the stove, kitchen island and aedicula – is intended as a reference to the barn and its outbuildings. Making all three new functional objects appear like variations of each other – part of a family of things – exactly like the three agricultural structures, turns the barn into a microcosm of the site itself.

“I love how the barn looks when the light goes,” says Bernstein. “The whole atmosphere changes.”

Jankes Barn is a rare example of a historic, timber-framed barn being creatively reimagined as a home, while retaining the building’s soul. By maintaining the spatial integrity of the building, and working with the landscape, architect and client have achieved an unusually harmonious response to the site and a wonderfully evocative – and still very much vital – piece of the Essex countryside.

Project team

Architect Lynch Architects

Garden design Joanne Bernstein Garden Design

Structural engineers Rodriguez Associates

M&E engineers Max Fordham

Heritage consultant David Andrews

Specialist timber contractor Joseph Bispham

Main contractor John W Younger Ltd

Downloads

Location Plan

PDF, Size 0.69 mbSite Plan

PDF, Size 0.87 mbLong Section E-W looking north

PDF, Size 0.65 mbLong Section E-W looking south

PDF, Size 0.58 mbLong Section N-S through courtyard looking west

PDF, Size 0.39 mbShort Section N-S looking east

PDF, Size 0.39 mbShort Section N-S looking west

PDF, Size 0.41 mb

No comments yet