Satish Jassal Architect’s Rowan Court helps to restore a sense of place for an under-utilised edge site on an existing council estate, writes Ben Flatman

Council housing has seen a notable resurgence over the past decade in a shift that marks a welcome change after decades of decline in publicly owned housing across the UK. This revival, albeit modest, is likely to play an increasingly important role as the Labour government seeks to build 1.5 million homes over the next five years.

And, as Labour promises to boost social housing delivery, exemplars of good design become ever more important in demonstrating how to build well.

The new wave of council housing is seeking not just to address the housing crisis, but to rehabilitate a typology that has long been maligned by much of the media as either poorly designed or the type of housing that the aspirational should avoid. Satish Jassal Architect’s Rowan Court development, located at the edge of an existing council estate in Seven Sisters, north-east London, offers a model of how to rewrite this narrative, delivering council housing that elevates not just its inhabitants, but its entire context.

Rowan Court, for client London Borough of Haringey, consists of 46 new council homes, built to a tight social housing budget. The scheme’s achievement lies not simply in the delivery of much needed homes, but in its response to the site – a previously underutilised corner of a housing estate.

By looking beyond the initial brief, which was for a relatively conventional infill scheme, Satish Jassal, founding director of Satish Jassal Architect, was able to convince the client to conceive of the project as something far more ambitious – a piece of sophisticated placemaking that enhances the existing context, and more than compensates the local community for any perceived loss of amenity.

Jassal describes the project as a step towards building not just homes but a “stronger community”.

An urban infill site

The site sits on Remington Road and Pulford Road, close to Seven Sisters Road, and backs onto a grade 1 ecological corridor which runs along the side of the Gospel Oak to Barking railway line. Once covered by Victorian terraces, by the 1970s the land had been cleared and left as an open but poorly defined green space, bordered by lock-ups and bisected by an electricity service tunnel.

Similar often forlorn patches of turf surround many council estates across the UK. They are the product of an approach to planning that saw public realm as being about percentages of open space on a site plan, rather than about how spaces are defined and used meaningfully. And, while infill on such sites is sometimes criticised for removing green space, there is a strong case for saying that – when done right – it can enhance the public realm, restoring a defined street line and coherent sense of place, and enhancing the existing context.

Initially appointed to develop a triangular plot for 12 homes, Jassal soon recognised the potential for a more ambitious scheme which would restore the site’s urban integrity while increasing housing provision. “The project is about townscape and placemaking,” he explains.

“We wanted to think beyond our red line and integrate the design with the existing estate and streetscape. You don’t need 2,000 homes to do this – you just need to understand and enhance the context around you.”

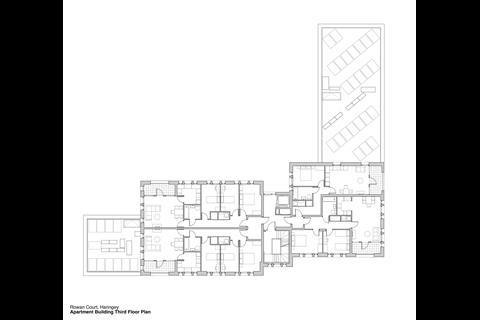

Key to transforming the development from conventional infill to a piece of urban restitching was Jassal’s proposal to create a new mews street to the east, and to expand the scheme onto a strip of land to the west along Remington Road, formerly occupied by dilapidated garages. This expansion allowed for a more integrated urban set piece: a six-storey corner apartment building anchors the scheme, flanked by lower apartment blocks and terraced housing.

And what was once a nondescript turning circle on Remington Street is now a defined urban public space, featuring a landscaped square at its centre and a pedestrian route connecting to Seven Sisters Road.

Restitching the urban fabric

Jassal has an extensive background in large-scale private sector residential development, including at East Village, Stratford and London Dock in Wapping. His ability to think beyond the site and dogged commitment to quality means that Rowan Court delivers for its residents and the surrounding community in a way which far exceeds the ambition of the original brief. This is largely thanks to the urban-design approach that the architect has brought to bear.

“One of our primary objectives was to enhance the public realm, including the existing estate,” Jassal explains. The improvements include new paving, lighting, planting and the installation of dedicated bin stores for the existing residents. Additionally, a new public square has been created for the entire community.”

The development includes buildings ranging from one to six storeys, thoughtfully responsive to the estate’s original architecture. The buildings step up from one, two and three-storey dwellings to six storeys adjacent to the existing six-storey council blocks.

“This really was about townscape, and the different buildings respond to what’s already there”, says Jassal. The varied building heights and staggered blocks enhance the area’s character, adding interest while respecting the neighbourhood’s scale and rhythm, stepping down to address the new public square.

Much is made currently of the need to reuse existing buildings, but it is often overlooked that many of our townscapes are damaged and in urgent need of repair. This is where intelligent new-build and infill can play a vital role, alongside retention of existing buildings, to help strengthen a sense of place and local community.

Rowan Court does precisely this, by repairing the frayed edges of the existing council estate. By creating a better defined sense of the public realm, including a more conventionally overlooked street, the scheme strengthens the existing estate.

Access to the site from the east is through a double-height passageway along Seven Sisters Road, originally an entrance to a tram depot. The existence of this link meant that the site achieved a higher PTAL rating through manual calculation, which planners use to assess the connectivity of a site to public transport. Closer proximity to the nearest transport node at Seven Sisters Station meant that higher densities were permitted.

This route, formerly uninviting and poorly lit, has now been transformed. “This wasn’t the most attractive or safe route – you probably wouldn’t have wanted to walk down here at night time, so we created a new overlooked mews street,” Jassal explains.

“We opened up the pathway and relandscaped it,” he notes, turning what was “previously overgrown” into a well-lit, secure route as a key element within the masterplan.

This revitalised link promotes the movement of people through and across the site – turning what was previously uninviting, into a well-used pedestrian journey.

Jassal describes the approach as “re-establishing the urban grain”, stressing the importance of integrating new forms into the local context. “It’s not about building a standalone complex; it’s about strengthening what’s already here and working with the local texture and scale.”

Where there was previously a hammerhead turning area for large vehicles, the masterplan has introduced a new mews street to strengthen the connection to Seven Sisters Road. The mews has three one-bedroom homes, and a single-storey wheelchair-accessible home that steps down to avoid overlooking and daylight conflicts with existing homes to the rear of Seven Sisters Road.

“Working on social housing means balancing standards with usability,” Jassal says, explaining that elements like plays spaces, dual-aspect apartments and community open spaces are essential. “It’s not about adding features just because they’re mandated; it’s about creating a framework of spaces that people genuinely desire to use and take pride in, fostering a sense of community ownership.

“For instance, in part of the public square, local residents have established and maintained their own garden. This initiative was achieved through collaborative co-design processes with the existing residents, who identified and established this space for themselves.”

A fascination with brick

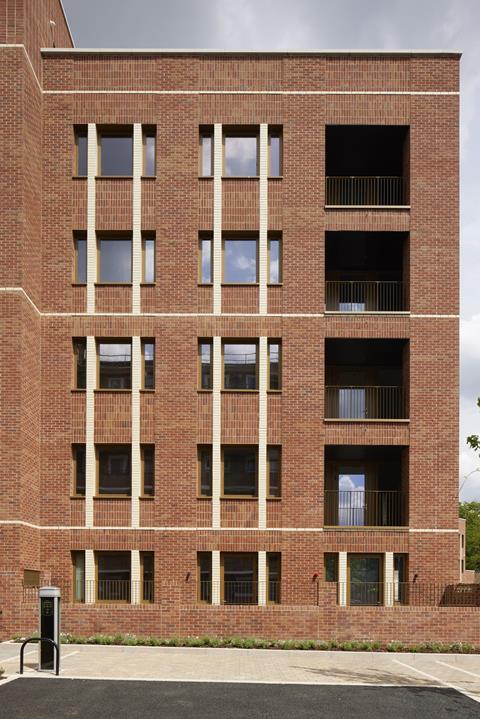

Jassal is perhaps best known for a string of ingenious houses on challenging small sites, including the RIBA prize-winning Southwark Brick House. The use of brick links these schemes to each other, but also to Rowan Court and a growing portfolio of larger community and housing projects the practice is working on. Jassal has a particular fascination with exploring the material’s rich potential, utilising a wide range of bonds to animate and articulate his facades.

“None of our projects have particularly high budgets, but we experiment with brick bonding techniques,” Jassal says. “On this project, we also introduce semi-glazed bricks to break up the buildings and create a rhythmic pattern for the facades that face public spaces. This is inspired by the established architectural rhythms we observe in the surrounding area and in London as a whole.”

At Rowan Court, the practice’s extensive experience has been put to particularly good use. Brick can – and often is – used monotonously, without any apparent interest in the material’s potential for variety, and the sense of solidity and depth it can convey within a facade. Here, the practice has given free rein to its fascination, mixing bonds and brick colours to create a lively and carefully articulated facade treatment.

“What I like to do is to understand the possibility of a material and use it to its fullest,” he explains. “If you use too many different materials, there is a monetary and visual cost.

“I don’t think good design is about just throwing expensive materials at a project. Materials need to be well chosen and work together. When you understand the material, it tells you how it should be used.”

The main six-storey block has an in-situ concrete frame and the lower structures have a lightweight Metsec steel frame, which the contractor proposed for speed. The brick facades were laid by hand on site, with no use of slips or off-site panelised systems.

“We’ve used brick not just as a facade material but as a way of adding depth and permanence,” Jassal says.

Material choices reinforce the connection to the area’s architectural language. The facades and subtle detailing mirror the warmth and solidity of surrounding residential buildings. The two types of brick and a combination of horizontal and vertical bonds create visual rhythm across the development.

Working with the community

The new housing is part of Haringey council’s ambitious home building programme, which is aimed at building 3,000 new council homes by 2031. In recent years, the council has made significant efforts to tackle the borough’s housing shortage by delivering new council homes for social rent.

Rowan Court is a flagship of the council’s housing delivery programme, set up to meet demand from those on the housing register in need of secure, long-term accommodation. Jassal’s commitment to meaningful urban design ensured early engagement with residents through 3D walk-through models and visuals, allowing them to see how the project would enhance their environment.

“We carried out a number of consultations with the existing residents on the council estate,” he explains. “What we tried to do was to persuade them that we’re improving the estate, not just creating more units.

“Nobody really objected to the principle of the development, as I would like to think they could see how it would improve the environment in which they live.”

Rowan Court seeks to strengthen community life on the estate by prioritising shared spaces for community interaction. The public square and a new communal courtyard behind the six-storey corner block encourages social engagement among residents, both new and established. The “porous” development strategy, with open, overlooked spaces, is grounded in accessibility and inclusivity.

Meeting diverse and intergenerational needs

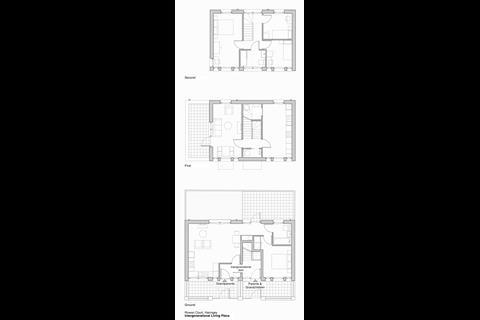

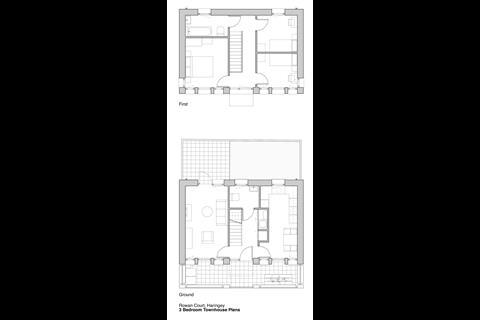

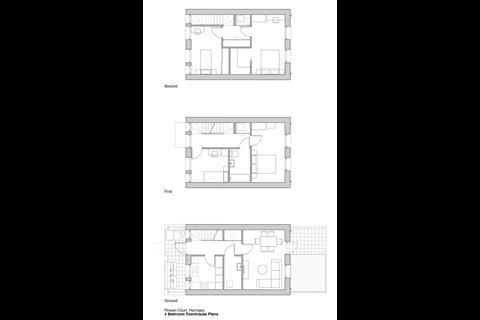

The design includes various housing typologies, from one-bedroom homes and four-bedroom family townhouses to intergenerational homes and wheelchair-accessible apartments, catering to a diverse range of households. The housing mix comprises 12 one-bedroom homes (26%), 16 two-bedroom homes (35%), 14 three-bedroom homes (30%), and four four-bedroom homes (9%).

“This is about creating homes that people can grow in, stay in and pass through over generations,” Jassal says. “Three-bed family homes are hugely in demand in most boroughs of London, especially affordable homes.”

The fact that Rowan Court potentially caters to such a wide range of residents, from single people to extended families, is a reflection of the client’s commitment to meeting local needs, but also to Jassal’s own interest in how we better address the challenges of multigenerational living.

Some of the homes have been specifically designed with extended families in mind, with ground-floor apartments suitable for grandparents or young adults, and upper-level three bedroom maisonettes intended for families with children, offering proximity with privacy. These homes also have the potential to be interconnected through a soft spot in the wall that could allow for an interconnecting door from the ground floor hallway, should an extended family ever want to have more direct connection. “Potentially these could be intergenerational homes”, explains Jassal, “with the grandparents at ground floor and a three bed maisonette for the family with grandchildren above”.

Several wheelchair-accessible homes ensure that the development accommodates residents with varying mobility needs. Public spaces are equally welcoming, featuring a new square, a shared courtyard, and improved pedestrian links that foster interaction and community cohesion. “The aim is to create spaces where everyone – young and old, female, male and nonbinary, new and long-term residents – feel as if they belong,” Jassal explains, emphasising the value of shared spaces that promote safety and openness.

Sustainability

Rowan Court’s commitment to environmental sustainability is as strong as its focus on inclusivity. The development prioritises cycle storage and pedestrian access, with limited parking for blue badge holders and car-share vehicles. Solar panels and air-source heat pumps supply over 80% of the energy in operation based on GLA guidance, significantly reducing the estate’s carbon footprint.

Jassal’s approach of “thinking beyond the red line” in particular for council-led housing extends environmental benefits to the surrounding area, and the landscaping also contributes to local biodiversity, with new trees and extensive planting that enriches the estate.

Challenges and Adaptations During covid-19

Construction of Rowan Court coincided with the covid-19 pandemic, bringing rapid increases in construction costs. “When we started on site in 2023 we had issues with inflation, and the material costs went up, so there was a process of review that we went through, in particular with the facade design, in collaboration with the client and the design and build contractor,” Jassal explains.

“We were appointed as the design guardians to the design and built contract. The contractor made it clear where the cost pressures were and we worked with the contractor to change certain design elements, but to keep the integrity of what we were trying to do. In particular from an urban design stand point.”

Jassal believes the fact that the client and local planning department remained supportive in terms of maintaining the overall quality of the development was also critical. “If everyone is working together, you can usually find a solution.”

Rising costs prompted adaptive design decisions, with aluminium spandrel panels replaced by brick, a change that arguably strengthens the scheme’s urban presence. Jassal also insisted on retaining the subtle changes in depth in the facades instead of a flat brick facade with punched windows.

“Good design doesn’t mean expensive materials,” Jassal notes. “It’s about understanding the possibilities of what you’re working with.”

Lasting impact

The Rowan Court project exemplifies the vital role of architects in not just supporting housing delivery but in actively shaping the urban fabric in ways that are inclusive, sustainable and enduring. It challenges the narrative that social housing must compromise on quality, proving that thoughtful design can elevate even the most challenging of sites.

By engaging with the community, embracing the area’s architectural DNA and integrating high standards of sustainability, Jassal has delivered a development that strengthens the estate while setting a benchmark for future projects. “We wanted to prove that council housing doesn’t have to mean compromise on quality or ambition,” Jassal says.

His practice has succeeded by delivering a scheme that is not just a collection of housing units – it is an act of repair and reinvention, as well as a diverse family of homes.

Ultimately, Rowan Court stands as a powerful argument for investing in social housing which respects its context and its residents. It reminds us that building homes is about more than hitting targets – it is about enhancing lives, fostering communities and reinforcing a sense of pride in place.

Projects like this demonstrate the value of giving architects like Jassal the freedom to think ambitiously and holistically, showing how intelligent design that looks beyond the red line can reconcile the often conflicting demands of budgets, sustainability and social impact. As we face the pressing need for more housing, Rowan Court offers a hopeful blueprint for the future – one in which good architecture and urbanism is not the exception but the rule.

Project details

Client London Borough of Haringey

Masterplanners / Architects Satish Jassal Architects

Design and build contractor Formation Design and Build

Project manager JJC Advisory Limited

Ecology Tom Haley Ecology

Landscape Groundworks

Sustainability Iceni

Planning consultant MC Planning

Fire BB7

Transport Scott White and Hookins

Acoustics Aucricl

Sustainable urban drainage Sweco

Daylight and sunlight Right of Light Consulting

Trees Arboricultural Solutions

Structural Alan Baxter

M&E Hyrock

Suppliers

Brick Wienerberger

Paving Tobermore

Windows Denval Windows

Air source heat pumps Joule

1 Readers' comment