This laboratory in the University of Cambridge’s Botanic Gardens is the ideal habitat for botanists

’One man with half-a-dozen flower-pots may do more towards advancing botany than another will attempt with 20 or 30 acres of garden,” declared John Stevens Henslow – professor of botany and tutor to Charles Darwin – in an impassioned address to fellow members of the University of Cambridge in 1830.

“But the larger the number of living species that are cultivated in a Botanic Garden, the greater will be the facilities afforded to us all; not merely for systematic improvement, but for anatomical and other experimental researches essential to the progress of general physiology.”

This was a radical proposition. For Henslow, the botanic garden was to be a site of research into the fundamental structures and properties of plants themselves – a novel pursuit. He had spent the previous five years campaigning to secure an expanded 16ha site to replace the university’s meagre physic garden, a small plot dating from 1762, where medical students were taught solely about the medicinal use of herbs. It was described by a visiting Bavarian professor at the time as “about five acres of very bad ground” – entirely inadequate for a world-leading centre of research in an emerging discipline.

Credited with inventing the “practical class” and its accompanying “demonstration bench”, Henslow was a progressive teacher and encouraged his students to go out and make their own observations from nature. To him, the garden was an extension of the laboratory. His plan, finally realised on a plot of land a mile south of the city centre, still stands today as a grade II* listed heritage site. A “gardenesque” composition, combining both specimen plants and composed landscapes, it is home to clusters of exotic trees and a complex series of herbaceous “systematics beds”, all laid out according to his theory of species, bisected by a long east-west axis and ringed by a meandering loop.

One hundred and eighty years after Henslow secured this site, it now bears a gleaming stone temple to his legacy: the £82 million Sainsbury Laboratory, a building solely dedicated to “elucidating the regulatory systems underlying plant development”. We have come a long way from students smelling herbs on a patch of bad ground.

We have come a long way from students smelling herbs on a patch of bad ground

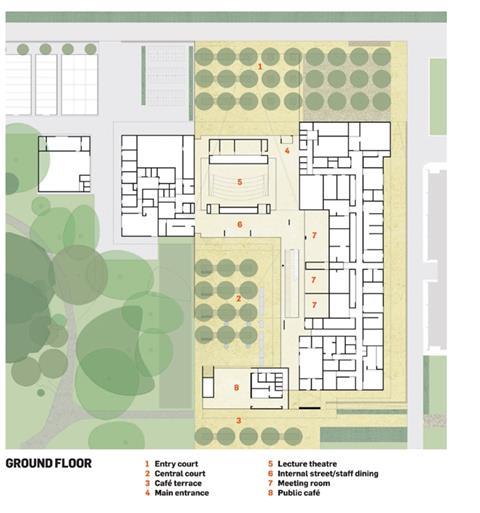

Sited in the north-east corner of the university’s botanic garden – in the back-of-house working world of sheds and tractors – this 11,000sq m research facility does a remarkable job of pretending it is not actually there at all. Accessed from an unlikely passage off Bateman Street to the north, and screened from the garden to the south-west by a mature grove of oaks and horse chestnuts, it hovers stealthily low in the landscape, not even reaching the roofline of the adjacent terraced houses.

“It is a hugely sensitive site,” says Gavin Henderson, director at Stanton Williams, as we walk down the new walled entrance avenue, a row of mews houses metres to our left and the listed garden landscape beyond a group of polytunnels to our right. “We have really tried to set the building down and give it a low profile – a third of it is underground.”

The narrow linear path screens our view of the building until it opens out into an expansive court, a 25m-wide square of York stone, planted with a grid of ginkgo trees. This courtyard brings us on axis with the full power of the building’s northern elevation: an unbroken 70m-long band of slender stone columns, marching along the first floor in a bold trabeated frieze. For those expecting a rickety old shed, or perhaps a compost heap, it is a startling sight.

Framed between sharp slabs of pale in-situ concrete, this perforated strip of honey-coloured limestone fins – named “pierre de soleil” for its buttery warmth in sunlight – appears to float across the width of the building. It seems only to be supported at its eastern end on a 3m-tall base of the same stone, with which it sits flush. Conceived as a monolithic plinth, this base is gradually recessed and eroded beneath the cantilevered upper storey as it progresses around the building, opening up completely towards the garden, and sometimes dissolving into a bed of gravel of the same colour. A third of the way along the northern front, it folds back into a glazed entrance, to which the entry court slopes down like a tilted tectonic plate, so that its stone surface extends deep into the building’s lobby. This is a simple series of moves, but it forms a powerful entrance sequence, using subtle shifts in the landscape to bring you from the street edge into the centre of the facility with maximum effect.

This majestic stone container sits in a wider ordered landscape of related facilities, each with its own specific role in the process of botanical research, “a bit like a working kitchen garden,” says Henderson. To the east squats a curvaceous glulam timber shed – the university’s Plant Growth Facility, designed by RH Partnership Architects in 2005 – beyond which lies a new complex of glasshouses, raised on top of a sunken level of controlled-growth chambers. There is something compelling about the pitched rhythm of the proprietary aluminium-framed glass sheds perched on the architect’s bespoke concrete plinth – “it is our own rustic temple,” jokes Henderson – Laugier’s version of the sophisticated lab building next door.

The language of permanence and flimsiness is elevated in the laboratory, itself conceived as a robust masonry shell, with secondary elements slotted into the frame. From the outside, it has none of the pretentions of a “flexible structure”, none of the wiry system-built language of so many modular scientific buildings. Instead, it is a wilfully monumental masonry box, but one, it turns out, that will stand plenty of adaptation within.

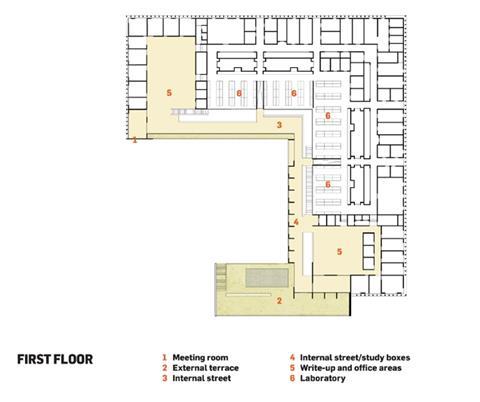

Entering this grown-up temple, the tilted entrance mat leads past a fully glazed wall to the central lecture theatre – the transparent forum-like heart of the building – to what Henderson describes as the “internal street”. An L-shaped space, with double-height voids cut through to provide glimpses of the laboratories above, it accommodates a dining area along one wing, while a stately, 20m-long timber staircase rises through the other. Framing two sides of an open central courtyard, this space is the social core, designed to facilitate interaction between the community of 120 scientists that will eventually be based here. The stair’s long treads force you to slow your pace, and its generous width allows two people to walk and talk, side by side, deep in botanical dialogue.

Upstairs, the social spaces continue, with a series of “study box” cubby holes set back from the lofty 6m-high space, lining the western facade of the southern wing. Modelled on Louis Kahn’s Exeter Library study carrels, these boxes are elegantly expressed on the elevation by recessed iroko panels set within crisp, double-order aluminium frames (which also serve to hide the structural steelwork propping the cantilevered slab). They are alluring spaces, but there is a touch of the first-class lounge about them, in their leather seating and oak-veneered panelling.

There is a touch of the first-class lounge about the leather seating and panelling in the ’study boxes’

Across the stair void from the study boxes, slightly raised up behind full-height glazing, lie the laboratories themselves – a visual proximity required, says Henderson, “because scientists never like to be too far from their labs”. These are generous spaces, flooded with natural daylight by curvaceous light wells that seem to mimic the profile of a scientific flask or bell jar, rising to 6m and shedding an even wash across the bespoke epoxy-resin lab benches. These are the kinds of rooms more often found in art galleries than research buildings, with an airy spaciousness and open aspect towards the garden, contrary to the usual model of a hermetically sealed prefab box.

Behind the labs are layers of support spaces, separated by a continuous band of risers – manufactured off-site and craned into place – and a single corridor that connects to outward-facing offices for the 12 “principal investigators”, as well as further practical rooms. Throughout, there is barely a single space that doesn’t have access to daylight, whether it be by way of a window in the facade or a recessed rooflight, and the circulation is carefully punctuated by cross-views for orientation, avoiding the usual warren-like nature of most institutional facilities of this scale. In these practical areas, walls are of studwork and occasionally blockwork, to allow for future changes – a flexible interior that belies the monolithic masonry shell.

The same organisation is repeated in the perpendicular wing, with open-plan write-up areas located at each end, along with two larger meeting rooms. Everything is on one level to encourage a sense of community, with continual views across the L-shaped plan certainly aiding the impression of a single open space – and, Henderson adds, “because we were told that scientists don’t do stairs”.

The southern wing leads out to a large stone terrace, the roof of a public café below that partially frames the third side of the central court, with views towards the botanic gardens and back into the facility. Conceived as a continuous concrete plane, this slab rises up to form a wall to the east, before wrapping over to become an overhanging ceiling, in a rather mannered move – less successful in its desire for public-facing novelty than the restrained clarity of the other elevations. From this level, steps lead down into the court, a slightly over-scaled stone space, planted with another grid of trees – this time olives, in keeping with the landscape concept of progressing from the grove of prehistoric ginkgo to this most cultivated of plants. Henderson likens these spaces to Darwin’s “thinking path”, the circular route he would walk in the grounds of Down House, deep in thought. There is a clear intention that the collegiate nature of the building’s design will aid both the social and intellectual working atmosphere of the place, with plenty of different routes and places to stop and talk.

Since the building has yet to be occupied, save for a couple of industrious researchers, these large open spaces can’t help but feel slightly barren, like the deserted forecourt of a grand hacienda. That said, although not strictly public, this central square has been proving popular with mothers and toddlers, who come to marvel in at William Pye’s water features, sparkling illuminated jets set into the ground, with any risk of getting wet safely removed behind glass. Let’s hope the trespassing continues.

Mothers and toddlers come to marvel at William Pye’s water features

One area that is already receiving much enthusiastic use is the public café, beautifully positioned to look on to the newly landscaped lawn of Cory Lodge, a listed Baillie Scott building that is now home to the garden’s horticultural team. A line of pleached lime trees extends the linear figure of the laboratory into the landscape, providing shade for the café tables. Meanwhile, low hedges frame the lawn, but retain a sense of permeability into the garden proper. A series of ground-floor rooms have also been provided at the end of the western wing for the garden staff, including a new mess room with its own secluded terrace.

Beneath all this, and explaining the apparent simplicity of it all, lie the sprawling bowels of the building, a whole floor humming with plant – a move that has left the rooftop enviously crisp and free from clutter. This level will also soon house the herbarium, rolling stacks of plant specimens – including the very samples Darwin brought back from the five-year voyage of the Beagle in the 1830s – safely secured behind a series of regulated antechambers.

As we leave the building, Henderson attributes the success of the project – which was impressively procured through a design-and build-contract – to the persistent push for quality from all sides, describing the process as “an amazing example of patronage” on the part of the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, a branch of the Sainsbury empire, and encouraged by the enthusiasm of John Parker, recently retired director of the botanic gardens. Competing for world-class researchers against other international institutes – including those Californian idylls, such as the Salk, that enjoy views out on to the Pacific Ocean – this building had to be designed as part of the draw, in the uphill battle of beach vs lawn, sun vs rain, Louis Kahn vs Stanton Williams.

There may be something a little overly slick about the result in places, but with the help of the university’s exacting standards , as well as the impeccable build quality from contractor Kier, the architect has succeeded in making this an impressive global contender, forging a lasting legacy of which Henslow would be proud.

1 Readers' comment