A project by Associated Architects for Wolverhampton University reminds us of the value of ‘persistent architecture’, writes Joe Holyoak

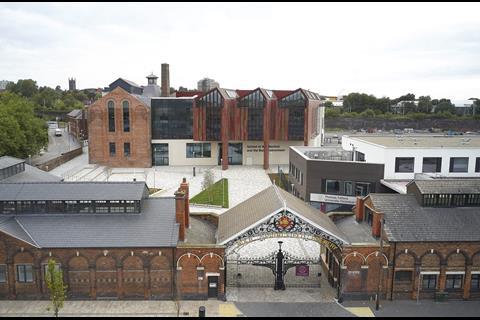

When Springfield Brewery in Wolverhampton was bought by the University of Wolverhampton in 2014, it was a basket case. Brewing had ceased there in 1990, and the buildings had gone into serious decline until much of the site was destroyed by a fire in 2004.

A developer purchased what was left with a miscalculated view to a residential development that never happened, and carried out work to the listed buildings without consent, before abandoning the site. It was a brave decision by the university to buy the ruins, but it has paid off.

William Butler built his brewery from 1873 onwards. Its massive red and blue brickwork buildings, pierced by arched windows and articulated by iron and steel sections, could have made it a candidate for inclusion in James Richards’ and Eric de Maré’s marvellous 1958 book on early industrial architecture The Functional Tradition.

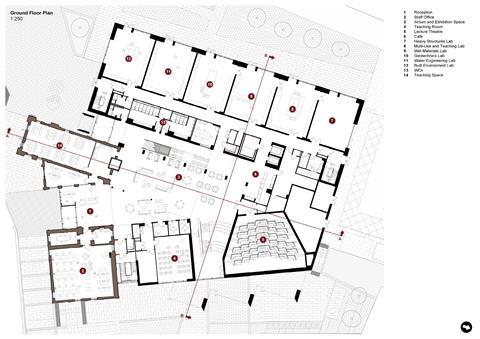

Working with Rodney Melville and Partners, Associated Architects won the university’s competition in 2017 to adapt the remaining brewery buildings, and add to them, to make a new campus for the School of Architecture and the Built Environment. It is now one of nine buildings shortlisted for the RIBA West Midlands Regional Awards 2023.

When adding or inserting new parts into old buildings which have previously served a different use, it is increasingly accepted practice not to try to clean up the old fabric. Instead, architects often now seek to conserve the signs of wear and tear that have been accumulated during a building’s previous life, to contrast with the immaculateness of the new fabric next to it.

This Associated Architects have done at Springfield, and the surviving brewery brickwork is eloquently scarred, patched, and layered with worn paint. It is maybe not as dramatic a juxtaposition as in the 2013 Stirling Prize winner Astley Castle in Warwickshire, where I recall a battered casement window surviving outside its modern replacement, complete with shards of broken glass hanging from the frame. But it certainly speaks of more than a century’s intense industrial activity.

We now have several justifications for the conservation and reuse of old buildings. The oldest one, dating back to William Morris and Philip Webb, focusses on the preservation of historic fabric, “ancient buildings as monuments of a bygone art”, as the SPAB Manifesto puts it.

Each successive usage inherits the history of its predecessors, giving its occupation an historical depth

The most recent justification is the zero-carbon argument for the reuse of existing buildings: the demolition of a building releases embodied carbon, and its replacement by a new building releases even more.

Thirdly, there is the economic argument that I learned from reading Jane Jacobs - that we need amortised old buildings in which to cultivate new businesses: “Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings”.

We might perhaps add to this list a fourth justification: one which is less tangible and difficult to document with evidence, but which I think I see working at Springfield. We could call it historical continuity. This is the idea that in the case of a building which passes through a number of uses over a long period of time, two things happen.

Each successive usage inherits the history of its predecessors, giving its occupation an historical depth which a completely new building, starting from scratch, cannot achieve. Secondly, by serving a number of functions over many generations, the building achieves the status of a permanent fixture in people’s perception of the evolving urban landscape.

Such a building absorbs history to itself

Aldo Rossi described this phenomenon in his 1982 book The Architecture of the City. His case study is the Palazzo della Ragione in Padua, a building dating from 1485 which has had a number of different functions over centuries of time. Rossi writes of it that “…it is precisely the form that impresses us: we live it and experience it, and in turn it structures the city”.

I don’t know the Italian term with which Rossi describes the historical continuity of such a building, but his translator uses the English word persistence, and the persistence of a building, continuing to exist while successively serving different purposes, is a necessary quality which justifies architectural conservation.

Such a building absorbs history to itself. Rossi observes that “…if the architectural construction we are examining had been built recently, it would not have the same value”.

Associated Architects have made some decisions at Springfield which add to the historical resonance. The school’s great atrium, through which everyone enters the building, fills the space of the brewery’s courtyard, where grain and hops arrived.

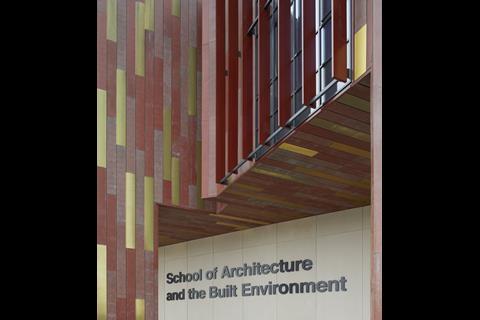

Its glazed roof establishes an axis with the brewery’s clock tower. The steel water tank on top of the tower brewery has been replaced by a similarly-coloured illuminated glazed box bearing the university’s name. Large precast concrete panels carry relief patterns derived from the brewery’s ornamental iron gateway from Cambridge Street.

One feels the historic presence of the brewery overlaying the new academic occupation. This memory could be reinforced if the university were to display some historic photographs of the brewery inside the school.

There is a thematic correspondence too. Next door is the new building of the National Brownfield Institute, by the same architects, and the Thomas Telford University Technical College. Together, these developments form a striking act of urban regeneration, which is an activity central to the school’s existence.

Associated Architects, winners of several RIBA awards in the past, deserve to win another for this school: I think it is possibly one of their best designs. (Full disclosure: I was their first salaried assistant, a very long time ago.)

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham

No comments yet