The ground below the n2 office development in Victoria was so congested by tunnels, it is supported in just four places. Thomas Lane looks at the pinpoint accuracy of the building’s fit

Later this year developer Landsec and Lynch Architects will add another piece to the complex redevelopment jigsaw around London’s Victoria station. Much of this has been shaped by Landsec, which is heavily invested in the area, including its own HQ on Victoria Street.

This local portfolio also includes Nova, a 727,000ft2 scheme spread over three buildings and the largest development ever undertaken by Landsec. Six years after Nova was completed, Landsec is putting the finishing touches to the next phase of the Nova masterplan.

Called n2, this project looks like it belongs to a different age. Nova is distinguished by its jaunty angles, cliff-like glass facades and blood-red highlights. N2 is a much more polite, sober affair with its monochrome, classical facades.

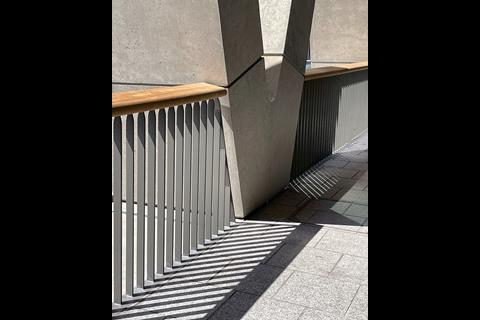

It does have one distinctive feature – huge, double-height, muscular concrete trusses at ground level. Superficially, these reference the much flimsier-looking inverted triangles adorning the base of the first phase, but are doing much more.

Architect Patrick Lynch describes n2 as looking like a swan paddling like crazy below the surface but looking serene and poised above it. This description is apt because the space below the building is jammed with underground structures.

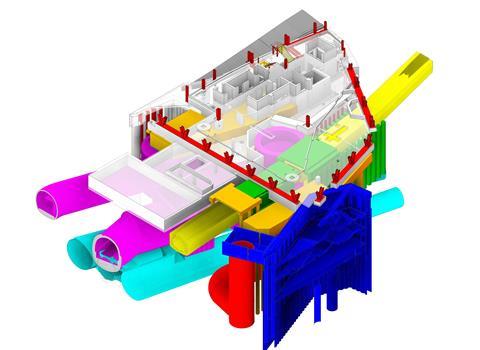

Developers like building near major transport interchanges as these appeal to occupiers, but the downside is the need to thread foundations through the infrastructure that makes the location so special in the first place. The designers and builders of n2 have had to contend with a particularly congested site. The Victoria line runs directly under the building and includes large diameter platform tunnels.

The Victoria station upgrade impacts heavily on this job, with the northern ticket hall secant piled wall impinging on the south-eastern corner of the site. This all new ticket hall necessitated new passenger-connecting tunnels to the District and Circle lines and escalators down to the Victoria line – all under the building.

If you exclude the core and basement, the entire building, which is essentially two-thirds of the of the area, is basically supported on four locations which are the only places where we could actually fit the foundations

Giorgio Bianchi, Robert Bird Group

And there is more: the King Scholar Pond sewer, a masonry arch structure with some concrete sections, is close to the surface. The Western Deep Sewer is 25m below the surface and is an unbolted, pressurised tunnel, that is to say the tunnel elements are not fixed together.

“It is very sensitive to the amount of pressure that you remove from around it,” explains Giorgio Bianchi, director of Robert Bird Group, the structural engineer tasked with negotiating through this maze. “Because it is unbolted, if you remove pressure from the top it becomes unstable. It is very important that the load from the soil above is maintained within certain limits.”

Bianchi explains that the congested nature of the ground left very few places for building foundations. “If you exclude the core and basement, the entire building, which is essentially two-thirds of the of the area, is basically supported on four locations which are the only places where we could actually fit the foundations.” Incredibly, an earlier design relied on just three support points, with the fourth point supported by a cantilever.

N2 has had a long gestation period, having been designed no less than three times. Landsec was in no rush to develop the site while the huge Nova scheme was being built out and let and the Victoria station upgrade ruled out any work.

The south elevation on the second iteration of the design, also by Lynch Architects, was positioned to create a soft corner at the junction of the road running in front of the building and Allington Street which connects this road to Victoria Street. The soft corner was needed to accommodate the turning circle of the now defunct bendy buses that used these roads.

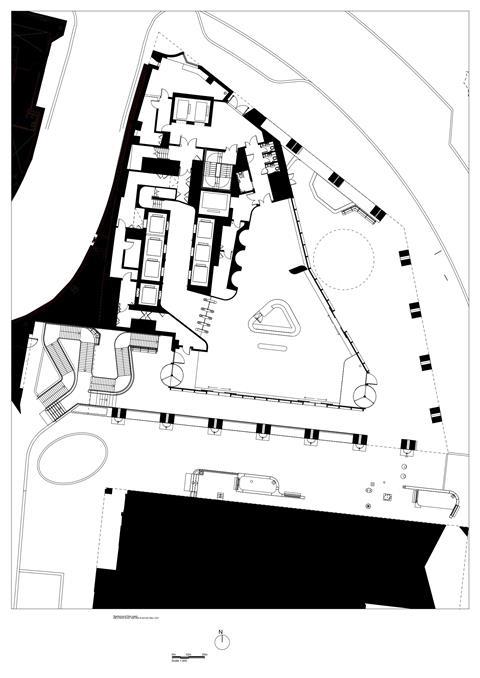

Landsec asked Lynch Architects to revisit the design for the third time in 2016, during the Victoria station upgrade work. Lynch proposed rotating the south facade clockwise by 15 degrees at its central point and rerouting the buses away from the development. This had several benefits including creating an uninterrupted east-west pedestrian route through the whole scheme and aligning the development with the Victoria Palace Theatre opposite.

This means the third phase of the Nova masterplan – Nova Place, which will be built onto the end of the theatre – will be a more rational shape. Crucially, rotating the facade meant the south-eastern corner could now be founded on solid ground rather than being supported on a cantilever.

“These things made it more efficient, quicker and easier to build and helped with viability,” says David Evans, director at Lynch Architects. “At the same time, we are absolutely convinced we have made it a lot better.”

Patrick Lynch says the planners loved the proposal, with the changes waved through as minor material amendment rather than a new application. “It was a complete alignment between our values, Landsec’s values and the planning department’s values.”

The density of the underground infrastructure meant the four areas where piling was possible were within the exclusion zones specified by London Underground and Thames Water for any work. A proposed, single pile in the centre of the building needed to be 1.8m in diameter and would be just 1.6m away from the Victoria line tunnels. Derogations were needed for these interventions.

“This meant we had to go on a journey with those third-party owners and prove to them that the impact of our structure would not be detrimental to their assets,” Bianchi explains. This was time-consuming as London Underground and Thames Water had to be satisfied the proposed work was safe.

“We ended up having a very honest and trustful relationship with both parties, which was key to the success of the project,” he says.

The core is located on the eastern side of the building, where there is no underground infrastructure. The basement is also located on this side of the building; level one occupies approximately half of the building area as this could be built over the Victoria line.

The presence of this line restricted the size of levels two and three, which occupy a small area next to the core; the primary function of these levels is to link n2 to Nova’s much larger basement next door. This includes a site-wide energy centre and houses bulky pieces of kit such as sprinkler tanks.

The south side of the building is supported by piles at each end, with the pile cap on the west side cantilevering over the passenger access tunnels and shafts. The east side is supported in one place by two 1.8m diameter piles of which one is 79m deep, formally acknowledged as the deepest pile in London.

“That is because probably a third of the building is supported on that specific asset,” Bianchi says. The fourth support point is located in the centre of the building.

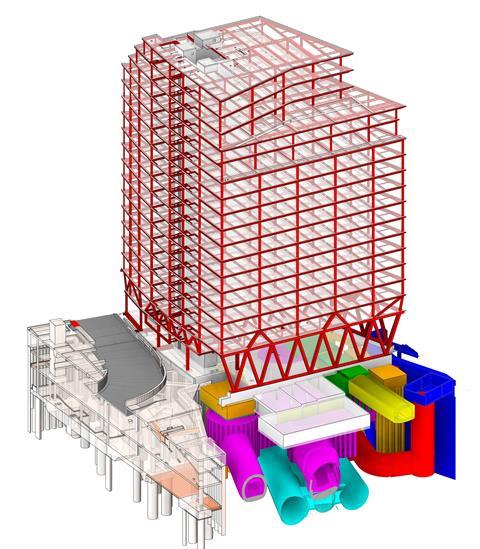

The limited number of support points called for a series of complex transfer structures and include those bold double-height trusses adorning the building perimeter. The truss on the building’s south side is effectively a bridge spanning the Underground tunnels, with the truss to the east cantilevering over the Underground ticket hall.

The building features a standard steel frame with composite floors based on a regular 9m x 10.5m structural grid above level three. This arrangement necessitated transfer structures to transfer the loads from the columns back to the giant trusses arranged around the building perimeter.

Three full-height trusses on level two span between the core and the eastern perimeter truss, which is why the latter needed such big, deep piles. Because the internal trusses prevent free movement at this level, the space has been used for plant, freeing up the upper levels for more valuable office space.

Keltbray was responsible for the groundworks and core with Mace taking on the main contract to build the office. Keltbray started on the groundworks in November 2019. Part of the work included the installation of a 900mm diameter test pile using a cement free concrete at the site.

Bianchi says the specifics of the piles needed for this job and the close proximity of the Underground infrastructure ruled out using it as part of the new building, but the test was nevertheless useful. “It allows you to be lot more efficient in the pile design because, by proving the capacity of the soil with a test pile, you can reduce the factor of safety on the design of all the other piles,” he says.

The original piles were to be 2.4m in diameter but the test showed this could be reduced to 1.8m. “If you go from 2.4m down to 1.8m, that is about a 50% concrete saving,” Bianchi says.

One of the most delicate elements of the groundworks was installing the 1.8m diameter pile 1.6m from the Victoria line. This was done during London Underground’s engineering hours, in other words in the middle of the night. A metal casing was driven in first; this extended down to the base of the Victoria line tunnels. With this protective casing in place, the main pile could be bored then cast.

Mace was engaged under a preconstruction services agreement in 2019 to finalise the design and engage specialist contractors. As part of this, Landsec funded the specialists to work up their design element and advise on buildability.

It is very rare where you have an opportunity to really dig into the weeds of the design to derisk it

Rob Dudley, Mace

“That helped derisk the design because you got the subcontractor design done very early and, working together, you pick up the key issues on the building before you start,” explains Rob Dudley, Mace’s project director on this job.

Mace put in its lump sum proposal in June 2020 but Landsec decided to hold off making a start, giving Mace more time to refine the design. Dudley describes this as time very well spent.

“It is very rare where you have an opportunity to really dig into the weeds of the design to derisk it,” he says. “The results were quite clear, the frame was built with literally a handful of site works which is quite rare. Those site works were just picking up a few bits and bobs with the interface with the core. It is probably the first job I have been on where you have built a steel frame without amending it as you go along.”

Mace got the green light to start in April 2021. The delayed start had the benefit of allowing Keltbray to substantially finish its part of the job before Mace started, which simplified logistics. “It allowed us a clean start,” Dudley says.

Orders were placed for the specialist packages just before inflation started to kick in. “We just about bought it before the prices started to escalate,” says Dudley.

An early job was installing the big concrete-encased steel exterior trusses. The long lead-in time meant the sequence of installation was well rehearsed.

“The biggest challenge, apart from physically lifting them in because they were big lumps of steel, was getting them in the right position,” Dudley says. “Once in position, they are very difficult to move, so getting that accuracy of position was key.”

The biggest piece of steel, on the east side, weighed 54 tonnes as this eliminated the need for site welding. Dudley says. “That came in over a night shift – we closed Bressenden Place and used an 800-tonne crane to lift it in. This saved time and money and was a job well done.”

The steel truss sections were bolted together. Dudley says it took three months to get the trusses in place, and after that the job was relatively straightforward.

The three trusses in the plantroom meant the MEP plant needed to be brought in early. “We had to get the big lumps of MEP plant in between the trusses before we started closing up the building because there was no way we could manoeuvre those around the floorplates,” Dudley explains. With the plant in place the cladding could start.

The concrete encasement of the external trusses is a key visual element and was used by Lynch Architects on the Zig Zag building, another Landsec project on Victoria Street. The concrete is ground smooth with different-sized pieces of aggregate adding visual interest. But getting the aesthetic right was a challenge, with the insitu concrete process employed on the Zig Zag building taking a long time.

Dudley says the team explored a number of options including using precast sections and glass-reinforced concrete, but these threw up more problems than they solved so the team returned to an insitu concrete solution, using the experience gained on the Zig Zag building to streamline the process.

A number of trial mixes were tested including on a full-sized mock-up. “The mock-up really paid off, that was where a lot of the detailing changes were made to achieve the desired effect and it also helped with the construction methodology as well,” says Dudley.

A lot of thought went into the formwork system as casting the concrete onto the long truss sections, which are set at an angle, was a challenge because it was difficult to ensure the concrete reached all the corners of formwork. Areas which were missed were patched in afterwards and blend in quite naturally thanks to the variegated nature of the finish. This was achieved by grinding the concrete smooth.

The building is due to complete before the middle of this year. For Landsec the long gestation period has been worth it as the building is now 66% let. James Rowbotham, head of workplace development at Landsec, describes it as a good example of the developer’s workplace strategy, with a BREEAM Outstanding and LEED Gold rating.

“What we are seeing, as hybrid working settles down, there is a strong demand for office space as people still want to come into work and go to places where they can collaborate with their colleagues and their clients,” he says. “They want to go to places where they can socialise outside work, and they also want a relatively easy commute. So that combination of amenity and sustainability is very much embedded in our workplace strategy and what you see at n2.”

The last part of the Nova masterplan to be developed is Nova Place opposite n2. This will wrap around two sides of the Victoria Palace Theatre. And over the road from n2 is Portland House, an early 1960s 29-storey brutalist office tower and local landmark.

In a sign of the times, Landsec has started refurbishing this building, whereas it might have been redeveloped had this work taken place a few years ago. Either way this part of London is slowly coming together as a destination, rather than somewhere through which people pass with barely a second glance.

Project team

Client Landsec

Concept architect Lynch Architects

Executive architect Veretec

Structural engineer Robert Bird Group

MEP engineer and QS Aecom

Project manager Gardiner & Theobald

Contractor Mace

Groundworks Keltbray

External trusses concrete J Coffey

MEP installation Lonsdale

Cladding Scheldebouw

1 Readers' comment