A new over-station development on Hanover Square shows how major infrastructure projects can catalyse the delivery of excellent placemaking, writes Ben Flatman

Placemaking has become central to wider debates about the built environment. And in central London developers are increasingly looking beyond individual buildings to the creation of quality places as a way of attracting tenants and maximising the value of their investment. Now a new commercial and public realm project around Hanover Square seeks to be an exemplar for how to achieve a strong sense of place in conjunction with a major public infrastructure project.

Much attention has been paid to the impact that the Elizabeth line has had on the capital’s transport connectivity, but also of huge significance have been the associated over-station redevelopments. At the new Hanover Square entrance to Bond Street station, Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands (LDS) and John McAslan and Partners (JMP) have worked collaboratively with clients GPE (formerly Great Portland Estates) and Transport for London (TfL) to maximise the Elizabeth line’s potential as a catalyst for transformation.

Hanover Square dates to back to the early 18th century but has seen significant change since its early days as a desirable residential address. Over the centuries it had become a slightly forlorn space – somewhere to pass through, rather than a destination in its own right. This was only exacerbated by its use as a turning point along several bus routes.

LDS director Paul Sandilands has been involved with the project for 15 years. He sees the station as a catalyst for Hanover Square’s public realm improvements and greater connectivity across the site. “The whole story is about the wider benefits,” says Sandilands.

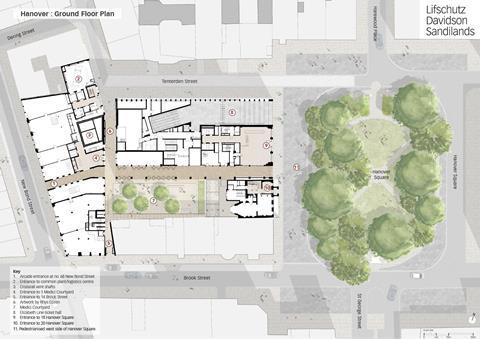

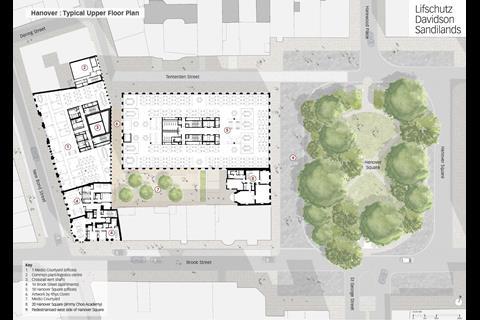

The reinvention of the square and its northwest corner consists of several key elements. Firstly, there is the new Bond Street station entrance by JMP, with its massive subterranean and above-ground infrastructure. Above this sits the large and yet skilfully scaled 18 Hanover Square office block by LDS. Then, in front of the station lies the partially pedestrianised and reimagined square by public realm specialists Publica.

To the south sits 20 Hanover Square, a restored Georgian mansion. And to the southwest there is a completely new public space, Medici Courtyard, by Bradley-Hole Schoenaich Landscape, which is flanked by further commercial and residential buildings by LDS, and a new pedestrian passageway leading to New Bond Street. The scale of the interventions is substantial, and yet it has all been expertly stitched into the surrounding context.

Public realm

Publica were brought onto the project at an early stage by LDS to advise on the public realm and pedestrian routes across the site. Anna Mansfield, a director at Publica, says the intention was to use the public realm strategy as a way to “unlock and open up” different routes across the site. Initially Publica focused on Medici Courtyard, which was conceived of as a new public space, subservient but also complimentary to Hanover Square.

As the new space was going to be contained and surrounded by relatively tall buildings, inspiration for Medici Courtyard was sought from Manhattan. Zion Breen Richardson Associates’ 1967 Paley Park was a key influence, with its informal seating and tree planting. Mansfield says the objective was to create an “intimate, small, found space… a place you discover.”

Although no investment had originally been allocated to Hanover Square itself, Publica encouraged GPE to commission some early-stage concept designs. These were then adopted by Westminster City Council, with strong support from WCC’s Head of Strategic Planning and Transportation, Graham King. The council went on to deliver the improvements to Hanover Square with funding coming from both the public and private sector, including GPE and other landowners.

Publica proposed a number of key changes to the square including ending its use as a turning space for buses. This then enabled the western side, in front of the station entrance, to be pedestrianised. New railings have been added that help define and enclose the listed garden at the heart of the square, which has been replanted to designs by landscape architect Todd Longstaffe-Gowan.

In addition, a vista has been opened up across the square from Oxford Street south towards the portico of St George’s Church. This was facilitated by the relocation of the historic Cabmen’s Shelter, which now sits in the northeast corner of the square.

The key to coherently integrating so much new development in a way that also respects and enhances the wider context, was GPE’s desire from a very early stage to work collaboratively with TfL, and the consequent close working relationship between LDS, Publica and JMP. Planning for the development started years ago.

GPE began acquiring property around the Hanover Square station location in 2006, well in advance of the 2008 Crossrail Act. It eventually assembled a 1.3 acre site, consisting of 13 different buildings. GPE then decided to offer its entire property holdings for the use of Crossrail.

This led to a complex sale and leaseback arrangement, with each party acting as freeholder and leaseholder of different parts of the scheme, with elements of the station spread across the site.

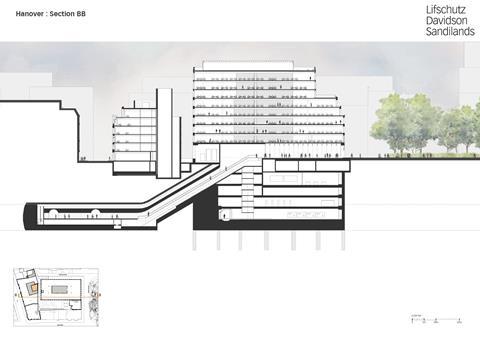

Although 18 Hanover Square appears to have been designed by one practice, much of the ground floor is actually made up of the ticket hall and station infrastructure and was designed by JMP. Meanwhile everything from first floor upwards is by LDS.

A shared design intent and the extensive use of a common material palette, helps to tie the elements together. Sandilands says LDS “worked closely with McAslan”, making the case that the building “has a consistency very hard to achieve” when two practices are involved.

The key engineering and space planning move came about when GPE offered space outside the compulsory purchase area to Crossrail for the huge vertical ventilation tower from the station below. This meant that 18 Hanover Square could be free of station plant above the first-floor deck level, enabling GPE to lease back and construct what for Mayfair is a massive commercial office building, with unobstructed floor plans.

As David Farries, senior development manager of GPE, observes, it has a “big footprint for Mayfair”.

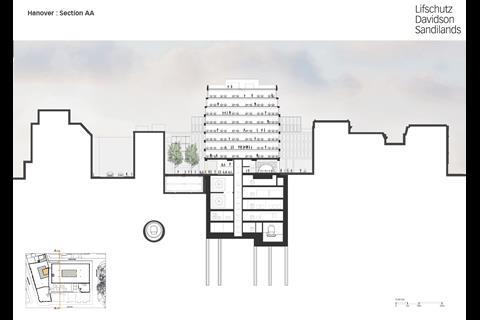

Number 18 is the highest building on Hanover Square by three stories. In the original 2011 planning approval, this was addressed through a mansard roof – a time-honoured method for adding more storeys in central London. But, as Farries observes, this was felt to be a rather half-hearted solution: “It was a bit apologetic, with the building never finished satisfactorily at the top.”

With the station already under construction in 2015, LDS then came back with a complete redesign, adopting a layered and stepped approach. Farries says it was a matter of “allowing your architect to be the architect”.

It’s a carefully proportioned building that has more than a little of the Manhattan skyscraper about it

Looking back at the previous design, he says: “We got rid of the mansard roof and gained more space, but we also got a better building.”

Sandilands believes that the building is “very much Mayfair”. Pointing across the square to James Cubitt & Partners’ 1959 Vogue House, Sandilands says: “We always loved the Vogue building. It’s what we aspired to.”

It’s a carefully proportioned building that has more than a little of the Manhattan skyscraper about it. Like Thomas Hastings’ Devonshire House on Piccadilly, with its setbacks and hierarchical composition, it is not hard to imagine an additional 50 storeys soaring above.

“a new gateway into the West End”

“We wanted to do something that had the longevity of the Rockefeller Centre,” says Sandilands.

Visitors to the Hanover Square entrance of the new station now arrive in a sober and restrained ticket hall designed by JMP. Associate JMP director Colin Bennie explains that the “the key” in terms of the practice’s design approach was to think about “the average commuter’s experience and needs”. Bennie, describes it as “a new gateway into the West End”.

“Daylight was key for both ticket halls,” says Bennie, before adding that “there’s a lot of McAslan house style – rigour and simplicity of materials”. There are bronze-framed ventilation panels and bronze-hinged grille doors that are closed at night.

>> Also read: Bond Street Elizabeth line station

Bennie says the choice of materials was driven by the 125-year lifespan of the project’s brief. “You have to design for a much longer timeframe,” he says. Fluted bronze columns are also intended as a refence to the London Underground stations of Charles Holden.

David Farries describes it as an “incredible project” with “a bit of everything – public realm, listed building, station”. The success of the project is “down to detailing and choice of materials” he says, before adding that it’s “very much a Mayfair building with a very contemporary take”.

The extensive public realm works by Publica represent a complex urban intervention in their own right. Sandilands says Publica were involved “very early on” to establish the pedestrian routes and how the overall development would integrate into the wider context.

On the western side of the square sits 20 Hanover Square, built in 1720. Designed by French-born architect Nicholas Dubois, many original features remain.

It has been given a thorough restoration by LDS, with Donald Insall Associates as expert consultants. The building has been let to the London Fashion Academy, a small private university, running courses that combine fashion design and business skills, funded by Jimmy Choo.

Behind 20 Hanover Square lies Medici Courtyard. It is an intriguingly ambiguous space that falls into that sometimes controversial category of privately owned public space. It is not dissimilar to a number of new private/public courtyards recently created in Fitzrovia, such as at Fitzroy Place (also by LDS) and Rathbone Square. These spaces are helping to bring back some of the porosity of 18th and 19th-century London, with its labyrinthine network of alleyways and passages, many of which have been lost or degraded during decades of site consolidation and wholesale redevelopment.

The minimalist landscaping of Medici Courtyard is by Bradley-Hole Schoenaich. To the south it is overshadowed by the rear elevations of offices on Brook Street, although there is coherence provided at ground level by a wall of travertine concealing plant related to the station below.

LSD’s work extends to the western end of Medici Courtyard, where the firm has undertaken a substantial facade retention scheme on New Bond Street. Here the design team has made good use of an existing entrance in the New Bond Street elevations to create a new pedestrian passageway.

Architecturally the LDS elements do not read as having been designed by a single hand, although they work well together. The residential and office elements at the western side of Medici Courtyard could have been by another practice. Meanwhile the back of 20 Hanover Square has been refaced with a new and entirely convincing Georgian-style elevation.

At the heart of its success, though, is the team’s commitment to collaborative working

The result is that this does not feel like another homogenous site consolidation scheme. LDS has made a virtue of a slightly disparate approach. Architecturally these buildings are not seeking to establish some “common language” and perhaps it is this that makes it feel more like London and less like a generic real estate development.

At the heart of its success, though, is the team’s commitment to collaborative working, and a desire to enrich the public realm. For once a major central London development feels as if it may have given back to London a little more than it has taken away.

An expert view

Nicholas Boys Smith, founder, Create Streets

Hanover is a splendidly skilful project: encouraging walking, improving Hanover Square, creating an arcade and a courtyard, artfully folding some height and heavy infrastructure into an historic context and infinitely preferable to the dreary porridge that was there before.

But heavens it is big isn’t it? Tenterden Street’s height to width ratio is overwhelming. It needs more rhythm. And the architects should have had the courage to permit more playfulness and pattern to create the coherent complexity that most people prefer.

Otherwise so many windows and such gaping doors risk becoming a spreadsheet not a face. More would be more. But this is doubtless London getting much much better.”

An expert view

Toby Lloyd, independent housing policy consultant and former No 10 special adviser

This project potentially points the way in terms of a mutually beneficial public-private approach to land acquisition and long term stewardship. GPE have had the vision to recognise the mutual benefit that could be achieved from a constructive partnership with TfL.

The end result is that the developer was able to produce a scheme that got more commercial value - as well as more high quality public realm and infrastructure - out of the site than a more typical adversarial tussle over a compulsory purchase order and planning.”

Hanover project team

Station client: Crossrail / Transport for London

Overstation development client: GPE

Station architect: John McAslan + Partners

Overstation development architect: Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands

Public realm consultants: Publica

Medici Courtyard landscape architect: Bradley-Hole Schoenaich Landscape

Multi-disciplinary engineer: WSP

Station contractor: Skanska/ Costain/ Engie

Commercial and residential contractor: MACE

1 Readers' comment