An account of what visitors found when being shown round the half-completed building by its architect Alfred Waterhouse

Site safety is one aspect of construction the Victorians did not excel at, but usually it would be the builders who are at risk. On a visit to the site of the Natural History Museum in 1876, it was members of the Architectural Association who found themselves narrowly avoiding a fatal accident. Workers on the scaffold above accidentally dropped two or three bricks, which landed within 2ft of the tour group and smashed one of the half-completed building’s terracotta tiles.

The piece below nonetheless gives a good sense of the state of the building three years into its construction and four years before it was completed in 1880. Designed by Manchester Town Hall architect Alfred Waterhouse, it was among the first buildings to be covered almost entirely in terracotta tiles, which could resist London’s sooty atmosphere. The tiles were also used for the interior, although those on the floor would be boarded over on the request of curators who ”find it exceedingly unpleasant to be constantly on a tile floor”.

The report, published in The Builder, the predecessor of Building Design’s sister title Building, also highlights the dangers of gas lighting at the time. Bottles containing fish preserved in spirit were deemed at risk of exploding if ignited by a stray flame, meaning that much of the building would remain unlit.

News item in The Builder, 5 February 1876

THE NEW NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, SOUTH KENSINGTON.

VISIT OF THE ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION.

The first of the Saturday afternoon visits of the Architectural Association for the present session to buildings in progress was made on the 29th ult., when the new Natural History Museum at South Kensington was inspected, so far as the dense fog prevailing at the time would permit. The visit was originally arranged for a fortnight earlier, but was postponed on account of the inclemency of the weather; and could the fog of Saturday last have been foreseen, another postponement would certainly have been made.

Notwithstanding the inauspicious state of the atmosphere, the members of the Association mustered from eighty to one hundred strong, and Mr. Waterhouse, the architect, having kindly arranged to be present and conduct the members over the works, the most was made of the occasion.

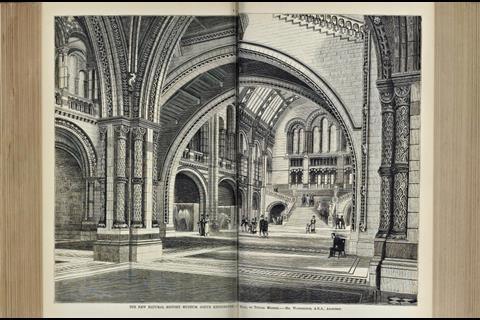

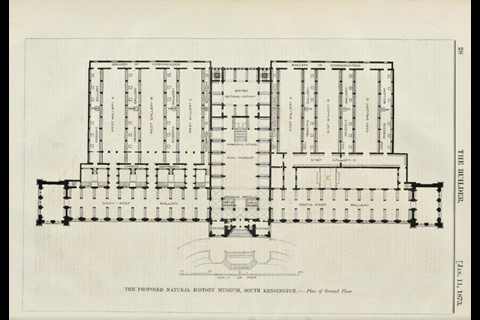

The building, as will be known to many of our readers, will exemplify the use of terracotta as an architectural and constructive material to an extent not yet carried out in any other modern English building, the whole of the façade and of the walls and architectural members of the interior being entirely of terracotta, with the exception that some if not all of the columns of the interior will carry the weight they are destined to bear by means of iron stanchions, which will be surrounded by terracotta. The style adopted is Romanesque, which Mr. Waterhouse explained is better adapted to the exigencies of the material than Italian or any other style.

The Museum, of which a view has already been given in the Builder, will present one very notable feature of arrangement, viz., the “Index Museum,” which will be the largest apartment in the building, and approached directly from the principal entrance in the centre. This “Index Museum” will, as its name imports, serve as a general key or guide to the whole contents of the Museum, and will form, together with the British Natural History Museum in its rear, the really popular part of the collections.

The building will be unique as to its ornamentation, which will be entirely based on the extinct and living species of birds, beasts, fishes, reptiles, and insects, of which examples will be exhibited in the museum. Of course these present an endless variety, and the manner in which the different specimens have been modelled by Mr. Dujardin (of Messrs. Farmer & Brindley’s) has met with the unqualified approval of the architect. The extinct specimens have been modelled from fossils now in the British Museum.

The floors will be of fire-proof construction, but boarded over instead of tiled, as curators find it exceedingly unpleasant to be constantly on a tile floor. The whole of the ironwork used in the building comes from Belgium, a fact well worth pondering over by British workmen. The stairs will be of stone; Mr. Waterhouse would have liked them in terracotta, but did not think it was possible to get the requisite truth of line in that material.

It is not intended to light the whole of the building with gas, on account of the extreme danger which would arise, owing to the fact that the fish are preserved in spirit. In case of fire the stoppers of the jars would fly out, and the burning spirit would be all over the place, carrying destruction wherever it went. It is contemplated, however, to close all portions of the Museum in the evening except the “Index Museum” and the British Natural History Museum, which will be, as before stated, the really popular portions of the building, and these it is proposed to light with gas.

The heating of the building will be effected by boilers placed below the British Natural History Museum. The foul air was originally intended to be carried off by the two towers, which were cut down by Mr. Ayrton, and which, though not included in the present contract, the architect hopes will be built in their integrity. If the towers are not built, some modification in the scheme of ventilation will have to be devised. The whole of the basement fronting the Cromwell-road will be occupied by workshops, the rear portions of the basement being devoted to store and lumber rooms.

In concluding his remarks in elucidation of the plans, Mr. Waterhouse, quoting the motto “Honour to whom honour is due,” said he had been most ably assisted by his old pupils, Messrs. Cooper and Isaac Steane, by Mr. Farquharson (clerk of works), and by Mr. Dujardin, who, as before stated, has modelled all the ornament.

A word or two on what, though a trifling incident of Saturday afternoon’s visit, might have been a very serious matter. It is always a sufficiently dangerous task to conduct a large party of visitors along the scaffolding of a building in course of construction, and it is therefore desirable that all extraneous sources of danger should be stopped while such a visit is in progress.

While the party was proceeding along one of the scaffolds at the Museum on Saturday last, some men who were at work on a scaffold above dropped two or three bricks, which fell within 18 in. or 2 ft. of several of the visitors, shattering one of the terra-cotta blocks. The men were of course ordered to stop working, but not until what might have been a fatal accident had occurred. In future visits it will be well if somebody in authority will think of the old adage anent the futility of locking the stable-door after the steed has been stolen.

More from the archives:

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

1 Readers' comment