French architects have built a reputation for imaginative reuse

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal are the winners of the 2021 Pritzker Architecture Prize.

The decision to give architecture’s biggest prize to the French duo, who founded Lacaton & Vassal in 1987, was announced by Tom Pritzker, chair of sponsor the Hyatt Foundation, this afternoon.

The pair are best known for their large-scale housing and cultural projects which always focus on reuse and other principles of sustainability.

“By prioritising the enrichment of human life through a lens of generosity and freedom of use, they are able to benefit the individual socially, ecologically and economically, aiding the evolution of a city,” said today’s statement.

The architects are celebrated for the way they increase living space through winter gardens and balconies that enable inhabitants to conserve energy and access nature during all seasons.

Their initial application of greenhouse technologies was at Latapie House in Floirac, France, in 1993. They installed a winter garden that allowed a larger residence for a modest budget. The east-facing retractable and transparent polycarbonate panels on the back of the home allow natural light to illuminate the entire dwelling, enlarging its indoor communal spaces from the living room to the kitchen, and enabling ease of climate control.

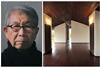

Other key projects include the FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais at Dunkirk in 2013 (pictured), the transformation of Paris’s Palais de Tokyo and a 59-unit social housing development at Jardins Neppert, in Mulhouse, France 2014–2015.

Martha Thorne, executive director of the Pritzker Prize and dean of the IE School of Architecture in Madrid, praised the “talent and continuous commitment of Lacaton and Vassal.

She said the award “shares a clear message about the important role that architecture should play in creating livable, beautiful spaces for all, while addressing larger societal challenges”.

“The 2021 Pritzker Prize Laureates approach each project convinced that what already exists (a building, site, surroundings) has value and that their role as architects is to appreciate, understand and embrace the existing, while respectfully adding new value through each project,” she added.

Tom Pritzker said: “Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal have always understood that architecture lends its capacity to build a community for all of society. Their aim to serve human life through their work, demonstration of strength in modesty, and cultivation of a dialogue between old and new, broadens the field of architecture.”

Lacaton & Vassal has completed more than 30 projects across Europe and west Africa.

Lacaton and Vassal are the 49th and 50th Laureates of the Pritzker Architecture Prize which last year was won by Grafton’s Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. Other winners include Zaha Hadid, Richard Rogers and Balkrishna Doshi, the first Indian winner.

>> From the archive: Building Study: Frac Nord-Pas de Calais, Dunkirk, by Lacaton & Vassal

>> Also read: RCKa’s inspiration: the Palais de Tokyo by Lacaton & Vassal

Jury citation

The work of Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal reflects architecture’s democratic spirit. Through their ideas, approach to the profession, and the resulting buildings, they have proven that a commitment to a restorative architecture that is at once technological, innovative, and ecologically responsive can be pursued without nostalgia. This is the mantra of the team of Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal since founding their Paris-based firm in 1987. Not only have they defined an architectural approach that renews the legacy of modernism, but they have also proposed an adjusted definition of the very profession of architecture. The modernist hopes and dreams to improve the lives of many are reinvigorated through their work that responds to the climatic and ecological emergencies of our time, as well as social urgencies, particularly in the realm of urban housing. They accomplish this through a powerful sense of space and materials that creates architecture as strong in its forms as in its convictions, as transparent in its aesthetic as in its ethics. At once beautiful and pragmatic, they refuse any opposition between architectural quality, environmental responsibility, and the quest for an ethical society.

For more than 30 years, their critical approach to architecture has embodied generosity of space, ideas, uses and economy of means, materials, and also of shape and form. This approach has resulted in innovative projects for residential, cultural, educational, and commercial buildings. Since their early projects, including Latapie House, the private house in Bordeaux, and civic works such as the proposal for the Human Science Center in Saint-Denis or the School of Architecture in Nantes, they have shown sensitivity and warmth of experience to their buildings’ users. The architects have expressed that buildings are beautiful when people feel well in them, when the light inside is beautiful and the air is pleasant, and when there is an easy flow between the interior and exterior.

The notion of belonging and being accountable to a larger whole involves not only fellow humans but the planet in general. From very early on, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal have consistently expanded the notion of sustainability to be understood as a real balance between its economic, environmental and social pillars. Their work has delivered through a variety of projects that actively address responsibility in these three dimensions.

The practice begins every project with a process of discovery which includes intensely observing and finding value in what already exists. In the case of the 1996 commission, Léon Aucoc Plaza, their approach was simply to undertake the minimal work of replacing the gravel, treating the lime trees, and slightly modifying the traffic, all to grant renewed potential to what already existed.

In their housing projects for the transformation of the Paris block, Tour Bois le Prêtre, and three blocks in the Grand Parc neighborhood in Bordeaux (both realized with Frederic Druot), instead of demolition and reconstruction they carefully added space to the existing buildings in the form of generous extensions, winter gardens and balconies that allow for freedom of use and therefore are supportive of the real lives of the residents. There is a humility in the approach that respects the aims of the original designers and the aspirations of the current occupants.

For the cultural center, FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais in Dunkirk, they chose to keep the original hall and attach a second one of similar dimensions to the existing building. Absent is nostalgia for the past. Rather, they seek transparency, openness, and luminosity with a respect for the inherited and a quest to act responsibly in the present. Today, a building that previously went unnoticed becomes an iconic element in a renewed cultural and natural landscape.

Source: Pritzker Prize

The 2021 jury

Alejandro Aravena (Chair) - Architect, Educator and 2016 Pritzker Laureate - Santiago, Chile

Barry Bergdoll - Architecture Historian, Educator, Curator and Author - New York, New York

Deborah Berke - Architect and Dean, Yale School of Architecture - New York, New York

Stephen Breyer - U.S. Supreme Court Justice - Washington, DC

André Aranha Corrêa do Lago - Architectural Critic, Curator and Brazilian Ambassador to India - Delhi, India

Kazuyo Sejima - Architect and 2010 Pritzker Laureate - Tokyo, Japan

Wang Shu - Architect, Educator and 2012 Pritzker Laureate - Hangzhou, China

Benedetta Tagliabue - Architect and Educator - Barcelona, Spain

Martha Thorne (Executive Director) - Dean, IE School of Architecture & Design - Madrid, Spain

Manuela Lucá-Dazio (Advisor) - Paris, France

Biography

Anne Lacaton (1955, Saint-Pardoux, France) and Jean-Philippe Vassal (1954, Casablanca, Morocco) met in the late 1970s during their formal architecture training at École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture et de Paysage de Bordeaux. Lacaton went on to pursue a Masters in Urban Planning from Bordeaux Montaigne University (1984), while Vassal relocated to Niger, West Africa to practice urban planning. Lacaton often visited Vassal, and it was there that the genesis of their architectural doctrine began, as they were profoundly influenced by the beauty and humility of sparing resources within the country’s desert landscapes.

“Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world, and the people are so incredible, so generous, doing nearly everything with nothing, finding resources all the time, but with optimism, full of poetry and inventiveness. It was really a second school of architecture,” recalls Vassal.

In Niamey, Niger, Lacaton and Vassal built their first joint project, a straw hut, constructed with locally sourced bush branches, which yielded surprising impermanence, relenting to the wind within two years of completion. They vowed to never demolish what could be redeemed and instead, make sustainable what already exists, thereby extending through addition, respecting the luxury of simplicity, and proposing new possibilities.

They established Lacaton & Vassal in Paris (1987), and have since demonstrated boldness through their design of new buildings and transformative projects. For over three decades, they have designed private and social housing, cultural and academic institutions, public space, and urban strategies. The duo’s architecture reflects their advocacy of social justice and sustainability, by prioritizing a generosity of space and freedom of use through economical and ecological materials.

Providing physical and emotional wellbeing has also been intentional in their work. Their application of greenhouse technologies to create bioclimatic conditions began with Latapie House in Floirac, France (1993). Using the sun, in harmony with natural ventilation, solar shading and insulation, they created adjustable and desirable microclimates. “From very early on, we studied the greenhouses of botanic gardens with their impressive fragile plants, the beautiful light and transparency, and ability to simply transform the outdoor climate. It’s an atmosphere and a feeling, and we were interested in bringing that delicacy to architecture,” shares Lacaton.

Through both new construction and the transformation of buildings, honoring the pre-existing is authentic to their work. A private residence in Cap Ferret, France (1998) was built on an undeveloped plot along Arcachon Bay, with the goal of minimal disruption to the natural environment. Rather than fell the 46 trees on the site, the architects nurtured the native vegetation, elevating the home and constructing around the trunks that intersected it, allowing occupants to live among the plant life.

Lacaton explains, “the pre-existing has value if you take the time and effort to look at it carefully. In fact, it’s a question of observation, of approaching a place with fresh eyes, attention and precision…to understand the values and the lacks, and to see how we can change the situation while keeping all the values of what is already there.”

Their skillful selection of modest materials enables the architects to build larger living spaces affordably, as demonstrated by the construction of 14 single-family residences for a social housing development (2005), and 59 units within low-rise apartment buildings at Neppert Gardens (2015), both in Mulhouse, France; and in adjoining mid-rise buildings consisting of 96 units in Chalon-sur-Saône, France (2016); among others.

Throughout their careers, the architects have rejected city plans calling for the demolition of social housing, focusing instead on designing from the inside out to prioritize the welfare of a building’s inhabitants and their unanimous desires for larger spaces. Alongside Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin, they transformed 530 units within three buildings at Grand Parc in Bordeaux, France (2017) to upgrade technical functions but more notably, to add generous flexible spaces to each unit without displacing its residents during construction, and while maintaining rent stability for the occupants. “We never see the existing as a problem. We look with positive eyes because there is an opportunity of doing more with what we already have,” states Lacaton. “We went to places where buildings would have been demolished and we met people, families who were attached to their housing, even if the situation was not the best. They were most often opposed to the demolition because they wished to stay in their neighborhood. It’s a question of kindness,” continues Vassal.

Current works in progress include the housing transformations of a former hospital into a 138-unit, mid-rise apartment building in Paris, France, and an 80-unit, mid-rise building in Anderlecht, Belgium; the transformation of an office building in Paris, France; mixed-use buildings offering hotel and commercial space in Toulouse, France; and a 40-unit, private housing, mid-rise building in Hamburg, Germany.

“Good architecture is a space where something special happens, where you want to smile, just because you are there,” shares Vassal. “It is also a relationship with the city, a relationship with what you see, and a place where you are happy, where people feel well and comfortable—a space that gives emotions and pleasures.”

Lacaton is an associate professor of Architecture and Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH Zurich (Zurich, Switzerland, since 2017), and a visiting professor at Polytechnic University of Madrid, Master in Housing (Madrid, Spain, since 2007). She has been a visiting professor at Delft University of Technology (Delft, Netherlands, 2016–2017) and Technische Hochschule Nürnberg Georg Simon Ohm (Nürnberg, Germany, 2014); was the Design Critic in Architecture (2015) and the Kenzo Tange Visiting Chair in Architecture and Urban Planning (2011) at Harvard Graduate School of Design (Cambridge, MA); and the Clarkson Chair at the University of Buffalo (Buffalo, NY, 2013). She served on the LafargeHolcim Awards jury for Europe (2017) and will be a member of the 2021 jury later this year.

Vassal is an associate professor at Universität der Künste Berlin (Berlin, Germany since 2012) and has previously taught at Technische Universität Berlin (Berlin, Germany, 2007–10); Peter Behrens School of Arts at the University of Applied Sciences (Dusseldorf, Germany, 2005); École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles (Versailles, France, 2002–2006); and École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture et de Paysage de Bordeaux (1992–99). He was head of the jury for LafargeHolcim Awards, Europe (2014) and a juror (2008 & 2011).

Together, they have held visiting professorships at Sassari University in Alghero (Alghero, Italy, 2014–2015); the Pavilion Neuize OBC-Palais de Tokyo (Paris, France, 2013–14); and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010–11). Lacaton and Vassal are the recipients of the BDA Grand Prize, 2020; Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, Cité de l’Architecture & du Patrimoine, 2018, with Druot; Académie d’Architecture, Gold Medal, 2016; the Heinrich Tessenow Medal, 2016; the Rolf Schock Prize, Visual Arts, 2014; Daylight & Building Components Award, Villum Foundation and Velux Foundation, 2011; the International Fellowship from the Royal Institute of British Architects, 2009; the Grand Prix National d’Architecture, France, 2008; and the Schelling Architecture Award, 2006.

Their practice, Lacaton & Vassal, has been awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award, Trienal de Lisboa (2016); and the Fundació Mies van der Rohe, European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture (2019) along with Frédéric Druot Architecture and Christophe Hutin Architecture for the transformation of 530 Dwellings at Grand Parc, Bordeaux.

Joint publications include freespace (Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal, on the occasion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia, 2018), The Incidents. Freedom of Use (Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Sternberg Press, 2015), PLUS: Large Scale Housing Development. An Exceptional Case with Druot (Editorial Gustavo Gili, SL, 2007), and Il fera beau demain (Anne Lacaton & Jean Philippe Vassal, Institut Français d’Architecture, 1995).

They work and reside in Paris, France.

Source: Pritzker Prize

No comments yet