Colin Bennie argues that today’s stations should be more than places of transit – they must inspire, connect, and offer permeability that embeds them meaningfully in the life of the city

During early development of the railways, infrastructure was often excluded from architectural discourse, dismissed as instruments of “material progress, speed and accelerated exchange”, as John Ruskin wrote. However, transport and station design has evolved over the past 200 years into a discipline which integrates engineering and architecture and, at its best, can elevate the everyday commuting experience and lift the soul.

The Elizabeth Line’s 2024 Stirling Prize win marks this change in recognising transport as equally valid for recognition where architecture and engineering align. It has helped to change perceptions of what transport architecture can do, raising the bar for future projects to be more than generic and bland spaces, infusing drama, excitement and identity as these projects continue to drive growth and renewal.

Evolution of transport architecture

Some of the great Victorian termini stand as examples of scale, maximising the drama of movement and creating memorable gateways into cities, becoming recognisable emblems of those places, such as Grand Central in New York.

When King’s Cross opened in 1852, there was no set precedent for station design. Lewis Cubitt approached it from first principles, creating a functional, double-shed structure – one for arriving and one for departing trains – with a flat-fronted gable elevation, and towers bookmarking the corners. This was a temple to the function and logistics of rail in its purest form.

In contrast, St Pancras, completed 14 years later, was designed for people not freight, prioritising grandeur. The engineer and architect worked on a shared masterplan – although perhaps from different points of view: the engineer for efficiency of movement, the architect in celebration of that movement.

Much of the visual power of the interiors of both stations comes from the way in which the soaring arches of the trainsheds allow the eye to capture the space immediately, properly closed at the ends as if by theatrical curtains hovering above the platforms. There are none of the distracting webs of secondary arches, braces and rods required by sickle-truss roofs – which distract from the theatre of movement.

Although we admire these structures, the lack of permeability across them and the relentless elevations alongside trainsheds are issues that recent renewals to both stations have sought to address.

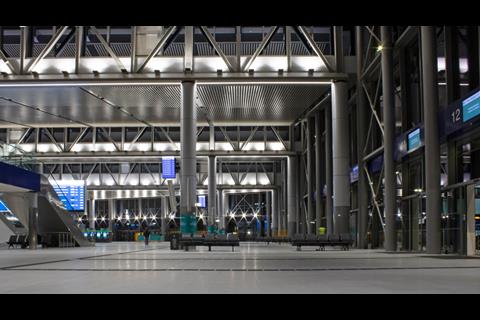

Many new-build post-war transport hubs are seen as generic and bland objects, lacking the civic scale and ambition of former termini – not places you actually want to be in – providing little to persuade users of the benefits of public transport over the modern predilection for the car. Often, the quality of these spaces is further eroded by ad hoc retail and incremental additions over time, a lack of pedestrian and urban integration, and general visual noise which undermines the user experience and sense of place.

So many modern stations preclude any sense of experience in the theatre of transport – an enriching part of a journey, and of marking those important moments of arrival and departure where stories start and end. Our transport hubs can and should be spaces that address a need beyond the function of travel alone.

Stations as urban catalysts

Transport architecture has the potential to shape and enhance its context. One entrance to the Elizabeth Line’s Bond Street station sits on the 17th-century Hanover Square, originally built as a garden square for residential townhouses. The green space – just one block from Oxford Circus – has been re-energised following the opening of the station, activating the urban realm, and drawing new creative and high-value business and footfall to the landscaped space in London’s largely grey West End.

Similarly, the sawtooth roof on the new Belfast Grand Central Station has been lovingly nicknamed locally as the ‘Seven Peaks’. And while the genesis of this was in exaggerating the sawtooth roof forms of the former linen mills which lined the site, the ambition to place the building within the landscape was one we wanted to embed from the outset. The station’s elevated mezzanine offers new perspectives of West Belfast’s skyline and the hills which embrace the city boundary, reinforcing a sense of place.

These stations serve as examples that transport can act as social and urban anchors when properly integrated. Beyond transit, they become community hubs, attracting leisure, retail, and amenities.

Permeability, activated edges, and mixed-use developments enhance engagement, fostering regeneration. Successful stations facilitate intuitive movement, clear visual connections, and open spaces that reduce stress and enhance security.

Designing for clarity and experience

The original King’s Cross had no booking hall – it wasn’t needed – but today’s stations have a role that extends beyond providing access to rail services alone. They are hubs of wider connectivity, convenience and amenity.

Their core function, however, depends on safe operations, clarity and legibility. Uncoordinated signage and ad hoc interventions disrupt cohesion, undermining both safety and user experience. Management of signage, lighting, seating, and artwork should be established from the outset.

This does not have to result in bland and formless design, but it does require commitment from all stakeholders – and to be maintained post-occupancy. Plus, inclusive design must extend beyond mobility, accommodating neurodivergent and elderly users with quiet spaces, intuitive navigation and information located in the right places and at the right time.

The future of transport hubs

Looking to the future, we need to consider a more joined-up experience, door to door, to drive further growth in public transport use. It is completely within our gift to deliver creative solutions that create greater comfort beyond the station itself and encourage people out of their cars.

Active travel and micro-mobility urgently require greater integration and legibility at a city scale. Clarity of purpose must be balanced with financial collaboration, but we can do better than a generic shopping mall approach. Instead, stations should remain architectural anchors, shaping their surroundings while offering functional, inspiring experiences.

As transport infrastructure continues to evolve, embracing drama and clarity in design will be key to ensuring stations are not merely transit points but vital components of urban life.

Postscript

Colin Bennie is a director at John McAslan + Partners, leading the infrastructure team on projects that have ranged from New York’s Penn Station to Belfast’s Grand Central

No comments yet