Explore the intricate restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, where centuries-old craftsmanship meets contemporary design

This past weekend, the Notre Dame Cathedral reopened its doors to the public for the first time since the devastating 2019 fire, offering a fresh look at its restored interior following five years of comprehensive conservation work. The reopening between 7 and 8 December marked a significant milestone in the cathedral’s reconstruction, showcasing the extensive repairs to its stonework, vaulting and timber roof.

The restoration was carried out using traditional craftsmanship and modern techniques, including the use of hand-hewn oak beams for the roof and advanced digital modelling. This approach reflected a broader commitment to reviving traditional skills, with artisans employing time-honoured methods to restore the cathedral’s fabric.

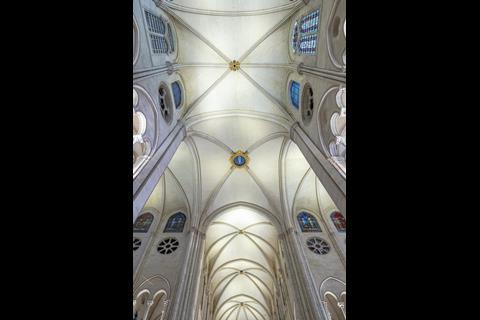

The completed interior now features a bright, cream-coloured stone finish, achieved through a painstaking cleaning process intended to remove soot, pollution, and fire damage. This process involved applying a latex paste to the stone surfaces, which was peeled off to reveal the original material. While the restoration aims to return the cathedral’s interior to a more luminous state, it has sparked some debate.

As Liz Smith noted in her recent BD column, “In an era when patina carries an age value that many appreciate as reflecting antiquity, the interior cleaning at Notre Dame could prove too much for hardcore conservationists.” Some have expressed concerns about the removal of the building’s natural patina, which many see as an integral part of its historic identity.

The restoration also highlighted the use of traditional skills, particularly in the reconstruction of the cathedral’s timber roof. Using methods nearly lost to time, carpenters employed “green wood” to rebuild the 13th-century oak structure, with each beam hewn by hand, reflecting a commitment to preserving age-old techniques alongside modern digital tools.

These photographs offer a visual insight into the monumental restoration effort, capturing the finished cathedral interiors, with ongoing external and public realm work as part of the broader project set to complete in 2026.

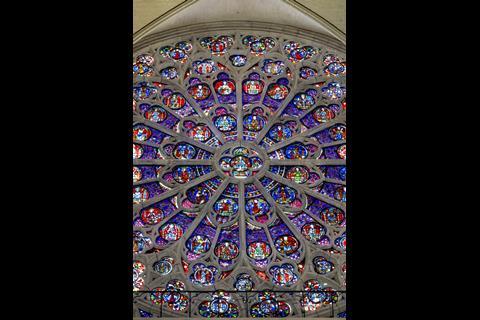

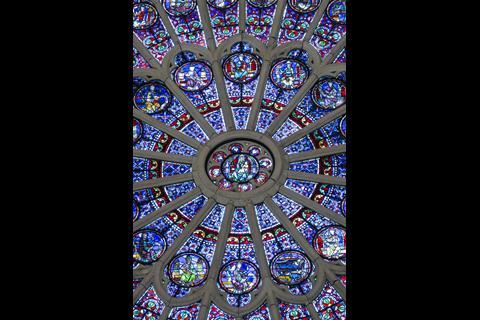

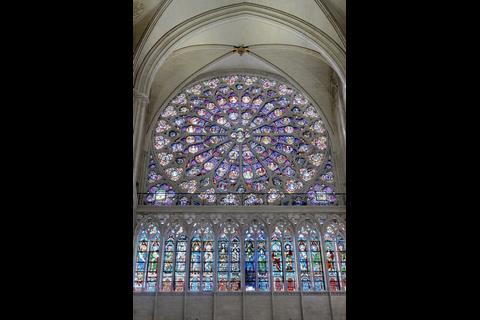

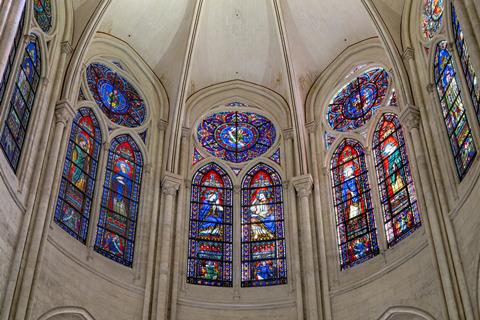

Windows and stained glass

Among the most significant features of the cathedral are its three rose windows, each a stunning example of Gothic craftsmanship. The south rose window, also known as the “midday rose,” measures almost 13 metres in diameter and depicts scenes from the Last Judgement, with Christ at the centre, surrounded by angels and saints. Its intricate design includes 84 panels spread over four circles, with symbolic numbers and references to biblical scenes. The north rose window, largely intact with its original 13th-century glass, depicts Mary with the Christ Child, surrounded by kings and prophets, while the west rose window, the smallest and oldest, showcases the Madonna and Child in the centre, with rays symbolising the 12 tribes of Israel.

As the cathedral reopens, a controversy over replacing some of Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century stained glass with contemporary designs continues to linger. While the heritage committee overseeing the project has unanimously rejected the idea, the proposal to introduce new stained glass, championed by President Macron, continues to provoke debate.

The ambulatory

The ambulatory of Notre Dame is designed as a walkway, allowing worshippers and visitors to move around the apse and nave. Unlike many cathedrals, Notre-Dame features a double ambulatory around the nave, defined by two rows of columns that form the side aisles.

When the cathedral was expanded in the 13th century, additional chapels were added along these side aisles. This distinctive arrangement of double aisles and a double ambulatory around the choir is a rare and significant feature in medieval church architecture.

Chapels

Notre Dame is surrounded by twenty-nine chapels, many added during the 13th century, with those located around the choir known as “radiating chapels.” During the Middle Ages, wealthy families often built chapels to ensure ongoing prayers and services for deceased relatives. These chapels were funded through foundations, with families offering annuities to chaplains in exchange for exclusive use of the space. As the 14th century progressed, the number of chapels and foundations continued to grow.

Each chapel was typically adorned with an altar, statues, paintings, and tombs, with some featuring elaborate wall decorations and relics of patron saints. Much of the cathedral’s chapel decoration was lost during the French Revolution, though some elements remain. Notably, the tomb of Simon Matifas de Bucy, bishop of Paris in the late 13th century, is the only surviving painted 13th-century decoration.

Contemporary interventions

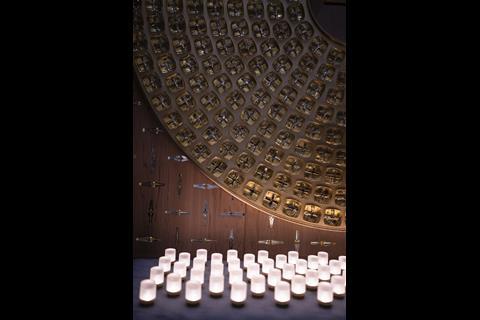

The new reliquary, designed by Sylvain Dubuisson, is inspired by the Crown of Thorns. Made of cedar wood, the reliquary takes the form of a large altarpiece. In the centre, a deep blue half-sphere surrounded by a golden halo creates a focal point for the Crown of Thorns when it is displayed. The reliquary also serves a practical function, with a secure compartment concealed within its base for the safe housing of the relic when not on display.

The new liturgical furnishings in Notre Dame have been designed by sculptor Guillaume Bardet. The five key elements – altar, cathedra and associated seats, ambo, tabernacle, and baptistery – are crafted from bronze. Bardet’s choice of bronze was inspired by the power of the cleaned stone within the cathedral, which he described as a material that manifests existence “without shouting” and “without over-showing.”

>> Also read: Notre Dame reopens: the power of craft, culture, and community

No comments yet