Despite eight centuries of history, Birmingham’s markets are being sidelined in the city’s latest redevelopment plans – with traders facing an uncertain future and no clear strategy for continuity, writes Joe Holyoak

In 1166, the Lord of the Manor of Birmingham, Peter de Bermingham, obtained a charter from King Henry II, permitting him to hold a weekly market. The market was held a few yards away from the de Bermingham home, the moated Manor House next to St Martin’s Church, in what later came to be called the Bull Ring. More than eight centuries later, the market is still running in approximately the same location.

As the small mediaeval town grew through the industrial revolution into a metropolis of one million people, the city centre migrated uphill to the west, with a more formal civic location grouped around Victoria Square and Chamberlain Place. But the Bull Ring remained the working-class focus of the city: less formal, more untidy, more socially dynamic. This remained true even after the area was transformed by the simultaneous arrival in 1963 of the Inner Ring Road and the Bull Ring Shopping Centre, which blew apart eight centuries of organic incremental growth.

The replacement of the 1963 shopping centre in 2003 by Hammerson’s Bullring (a horrid neologism) resulted in a displacement of the markets from their original location – moved further away from the central area to the opposite side of Edgbaston Street. Today, there is the outdoor retail market, opposite St Martin’s Church; next to that, the Rag Market building; and next to that, the Indoor Market, with floors of car parking above it.

The Bull Ring markets – the manifest evidence of eight centuries of urban tradition and the location of a vital element of the local economy and culture – ought to be highly valued and celebrated by the city council. Sadly, they are not.

Through all the physical disruption of the last 60 years, the market traders have been poorly treated, and their workplaces have been pawns in the constant game of spatial chess played by impersonal economic forces. Currently, the fate of the Indoor Market hangs in the balance.

The Smithfield masterplan for the redevelopment of the 1970s Wholesale Market site by Lendlease, which includes the three retail markets, has been the subject of two earlier columns for Building Design. The masterplan includes new accommodation for the three markets in Phase 1 of the development, due to start on-site in 2027.

As I wrote previously, the plans imply an unwelcome element of gentrification of what is, by definition, a relatively unsophisticated but affordable source of fruit and vegetables, clothing, shoes, shoelaces, meat and fish, and most other things you can think of.

>> Also read: Birmingham’s Smithfield regeneration project risks marginalising the communities who use its markets

Another issue to which I referred – one for which no satisfactory answer has yet been delivered – is how continuity of trading is to be achieved, given that the new markets will occupy approximately the same footprint as they do presently. This is a vitally important matter that you might imagine a masterplan would address.

Another thing you might imagine is that the Indoor Market building – with its exceptional fish market, a symbol of the city’s history and reputation – would be in municipal ownership. But it is not. It is owned by Hammerson, the owners of the Bullring shopping centre on the opposite side of Edgbaston Street.

The future of the Indoor Market seems to depend on decisions made by two large developers: Lendlease and Hammerson, with the city council as an ineffective bystander. At present, the two developers do not seem to be part of the same conversation.

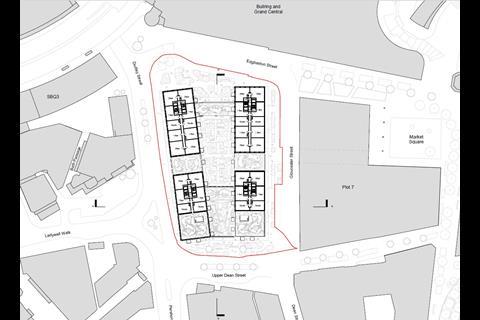

Hammerson’s Indoor Market site is, nominally at least, within Lendlease’s Smithfield masterplan, although there is little evidence of coordination between the two developers. Hammerson has submitted an outline planning application for the demolition of the Indoor Market building and its replacement with a high-rise residential development designed by Howells.

A statement by the agents Avison Young, submitted with the application, denies that Hammerson has any responsibility for the Indoor Market. It states: “Policy GA1.2 (of the Birmingham Development Plan) cannot be read as obliging Hammerson to provide new market space as part of its proposals.” When the statement refers to the loss of the Indoor Market, it puts the word ‘loss’ in inverted commas, as though it were an imaginary event.

Lendlease has at last addressed the issue of continuity of trading. The simplest and most obvious solution would be for the present Indoor Market to continue in use until the new one is built. But that would depend on a plan being agreed upon by Lendlease and Hammerson – one they seem unable or unwilling to consider. Instead, a decanting of traders into a temporary building is being suggested.

There is currently no approved scheme for a temporary indoor market and no funding for it

It is difficult to see how this could be achieved. Immediately behind the existing retail market sites, there is a four-metre vertical drop, resulting from the scraping out of a flat site in the 1970s for the big sheds of the Wholesale Market, now migrated to Witton.

The planning application was considered by the Planning Committee on 16 January and, after a short discussion, was wisely deferred. There has been widespread anxiety in the city, reflected in that discussion, about the future of the Indoor Market. It is not inconceivable that it might fall fatally into a gap between the two developers.

It was stated at the Planning Committee that there is currently no funding for a temporary market building. Neither developer is likely to offer to fund it, and in the city council’s present financial crisis, it may not be seen as essential expenditure by the government commissioners who are now overseeing all the city’s major financial decisions.

Howells’ design for the Indoor Market site is not the subject of this column, but it is worth mentioning, as it is surprisingly poor. It is an outline application, but the illustrative scheme seems to indicate what is intended. It features four towers linked together in a symmetrical plan – the tallest on Edgbaston Street with a maximum height of 210 metres.

It is an object building, apparently with little interest in the shaping of public space around it. Left-over spaces on the perimeter are filled in with trees and other planting.

It is possible that the problematic issue of the Indoor Market could have a satisfactory resolution. But it is difficult to see this happening. There has been a transference of authority over important public assets from the public sector to the private sector, into the hands of private developers who deliver what the market will pay for and have no responsibility for the provision and maintenance of civic resources.

The elected councillors and the planning officers seem unable to change this. It is a failure of planning. One kind of market is calling the tune – another kind of market could be a casualty as a result.

The Hammerson planning application will be heard for a second time at the Planning Committee on 13 February. This time, it is being recommended for approval. The case officer’s report states that the imposition of what is called a Grampian condition on the approval was considered.

This would prevent demolition until alternative accommodation existed. But this was deemed unreasonable, as Hammerson has no control over the provision of a temporary market building.

There is currently no approved scheme for a temporary indoor market and no funding for it. So it is likely that eight centuries of history, a vital resource to many citizens, and the livelihoods of hundreds of traders will be ended in the cause of private enterprise. Does this fulfil Rachel Reeves’ definition of growth?

No comments yet