Ugandan practice Peatfield & Bodgener survived the rule of one of the world’s most brutal dictators. Ben Flatman finds out how

Resilience is arguably the most important, unteachable, quality that any architect can possess. While talent and enthusiasm abound in architecture schools, few architects go on to achieve much without an underlying, steely ability to persist against all odds. So as the storm clouds of Brexit gather over Britain and a general sense of crisis seems to pervade the national mood, it’s worth being reminded that some architects have endured far worse turmoil and still survived.

Many practices have confronted the conventional pitfalls of recession, poor cash flow and litigation. Far fewer have had to navigate the extreme challenges that have faced the British-Ugandan practice of Peatfield & Bodgener over its 65 year history, from dictatorship through to civil war. When I recently met the firm’s current director, Irishman Philip Curtin in his tranquil Kampala office, I tried to gain an understanding of how Peatfield & Bodgener had weathered such a turbulent period in African history and lived to tell the tale. Curtin described an approach to architecture which has embraced the profession’s most entrepreneurial and bloody-minded traditions.

Thomas Peatfield and Geoffrey Bodgener were schoolmates who served together in the RAF during the Second World War. After being demobbed, they completed their architectural studies in London and went on to form a practice together in 1952. Like many young architects in the post-war era, Peatfield & Bodgener sought out commissions from amongst the remnants of Empire and the emerging independent nations of the British Commonwealth. From their office in a Georgian terrace on Blackheath, they entered a Commonwealth architectural competition in 1956 for a new national assembly building in Uganda. They won, and so began a project that would lead the practice on to remarkable success, and right through one of the most violent and tumultuous periods in Uganda’s history.

Like many a canny architect, when he arrived in Uganda, which was still a British protectorate, Bodgener set about rewriting the competition brief. He convinced the client that what was needed was something more ambitious and better suited to become the future parliament of an independent nation than a modest assembly building. The competition winning scheme soon evolved into something grander, with significant planned expansion designed in from the beginning. Joseph Mayo, a young architect with a talent for sculpture, was tasked with carving a huge wooden screen for the foyer, evoking everyday life in Uganda. Like much architecture that Britain exported to its former overseas territories, with its familiar campanile and bas-relief artwork, the finished building is as evocative of early post-war England as it is of post-colonial Africa.

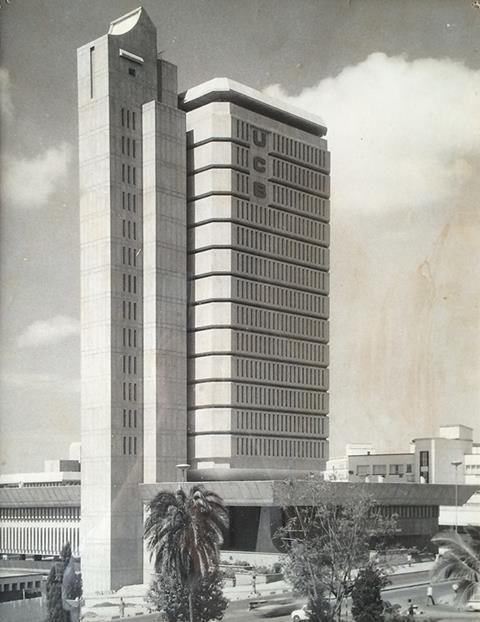

The debating chamber was completed in 1959 and on the back of the parliament building, the practice began to grow. At the time of independence the nearest architectural school was in Nairobi, and so in a country with few trained architects Peatfield & Bodgener were well placed to win the lion’s share of new commissions, including the landmark Uganda Commercial Bank building (now Cham Tower). The Kampala office was primarily run by Bodgener, with the support of another British partner, George Edmead, and focused on design, business development and construction. Back in the UK, Thomas Peatfield managed specifications and much of the tendering.

The early years in Uganda were extremely productive. Under the left-leaning leadership of Milton Obote, the first post-independence prime minister, Uganda began the process of state-building, 12 district hospitals were built in the late 1960s to early 70s, all designed by Peatfield & Bodgener. However, as the 1960s progressed, there were growing tensions within the young nation. Obote nationalised a swathe of British-owned businesses, and was accused of overseeing a culture of cronyism and corruption. By 1966 he had imposed himself as president and was facing growing dissent from minority groups and the army. In 1971 there was a military coup, soon followed by the assumption of power by Idi Amin.

During his first few years in power, Amin was by all accounts very personable. He was often seen out and about in his open top jeep or walking the streets on foot – seemingly an approachable ‘man of the people’. When Peatfield & Bodgener’s architectural photographer, Syd Adams almost ran over a pedestrian in the central business district and leant out of the window to berate him, he discovered the man he’d almost killed was Idi Amin.

But as time passed, the mood in Uganda changed. Bodgener would later recall a late night visit by Amin’s secret police, the “State Research Bureau”, who had come to confiscate his passport. It was not unusual for such visits to lead to arbitrary arrest, or worse. Unfazed, Bodgener decided to disarm his visitors by playing the archetypal Englishman, laying on high tea for the secret policemen in the middle of the night, dressed in a smoking jacket. They took the passport, but left Bodgener untouched and free to continue his work. In a climate of fear and arbitrary theft and violence, he adopted coping strategies, keeping his ostentatious Citroen DS parked in the garage and making sure to only be seen in an inconspicuous and less covetable Fiat 500 for trips around town.

As Amin’s erratic and increasingly oppressive style of government continued, so it brought progressively greater economic instability. Remarkably, Peatfield & Bodgener continued to practice and won a commission to design a new Bank of Uganda headquarters. The governor of the national bank, fearful that Amin would soon empty the nation’s coffers, demanded a design that could be constructed in just 9 months, before the money ran out. The architects responded by proposing a largely pre-fabricated kit of parts approach. At the time, it was expected to be the world’s largest multi-storey space-frame structure. However, the governor’s fears proved well founded. Work on site started in 1978, but as Uganda slid into turmoil, construction halted and the bank was left unfinished for almost a decade.

Amin was overthrown in 1979 and replaced by a returning Obote, followed by a period of protracted and particularly destructive civil war. Bodgener decamped to Nairobi for a short time, but Edmead remained in Kampala, often sleeping in the office to avoid the dangerous drive home at night. The practice’s offices at the time sat directly behind the central police station and Edmead would later talk of work phone calls being interrupted by the sickening sounds of the savage beatings and torture going on nearby. Shootings and violence were not uncommon on the streets. It is difficult to imagine a more surreally macabre and disturbing working environment.

Philip Curtin, a contemporary of former RIBA President Angela Brady at the Dublin Institute of Technology, arrived in Kampala at a moment of relative calm. Tired of his job designing housing at the Milton Keynes development corporation, Curtin applied for and was offered a job with Peatfield & Bodgener and touched down in Kampala in 1987, soon after Yoweri Museveni became president. Curtin’s early work in Uganda involved a lot of reconstruction and rehabilitation of the country’s ruined institutions, including the Makerere University campus in Kampala.

As Museveni set about the slow task of rebuilding the country from the ground up, work restarted on the unfinished skeleton of the national bank, still under the supervision of the ever-present Peatfield & Bodgener. Curtin describes how the practice began tracking down the various components of the building, which had been left in their containers at various ports and depots around the world. Some of the space-frame elements were still at the factory in Exeter from which they’d been ordered almost a decade earlier.

Peatfield & Bodgener still survives in Uganda today, having maintained a functioning office in Kampala throughout the years of Idi Amin, civil war and the rebuilding that followed. Most of the practice’s buildings are still also intact, although there is growing concern, recently highlighted by DOCOMOMO, about the fate of the National Theatre. Like the practice itself, the buildings are case studies of architectural resilience and survival.

1 Readers' comment