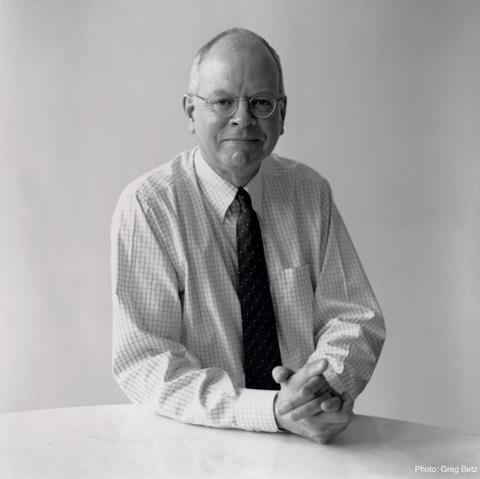

Chris Fogarty reflects on the legacy of his former colleague David Childs, a mentor and ambassador of American architecture

From my desk, where I’m writing this, I have an extraordinary view looking south over downtown Manhattan. One World Trade Center rises at the heart of it all – simple, powerful, and symbolic.

Its name, and the tragedy associated with it, encapsulate much of the past eighty years of American exceptionalism. Last month, its lead designer, David Childs, passed away.

I live in New York because of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. After finishing university, I worked in their London office for nearly five years. Somewhat unexpectedly, I was asked to lead the design department in the Washington, D.C. office in 1997.

A few years later, I moved to New York and began working alongside David on a new tower in Times Square, a proposed replacement for the New York Stock Exchange, and – after 9/11 – the rebuilding of the World Trade Center.

Whatever one might think of SOM today, its legacy reflects the ambition and optimism that defined postwar America. From the 1950s through the 1970s, buildings like Lever House and the Hancock Tower stood as confident declarations of American progress. SOM embraced the European modernism of Mies and Gropius and recast it in the image of corporate capitalism.

The firm’s architecture became an expression of America’s global influence – exporting ideals, whether welcomed or not. But by the 1980s, that paternalistic corporate ideal had devolved into deregulation and junk bonds, and SOM’s sleek internationalism gave way to postmodern pastiche. It took over a decade for the firm to recover its design direction.

David joined SOM in Washington in 1971 after working with Nathaniel Owings and Senator Patrick Moynihan on the redevelopment of Pennsylvania Avenue. He was an ultimate diplomat – fiercely intelligent, quietly political, and unfailingly gracious.

He cultivated client relationships and mentored younger designers, always encouraging them to do their best work. He was charming, patrician, and sophisticated.

I recall how at a public meeting in Virginia in 1998, an elderly woman approached me to ask about David. She vividly recalled how, twenty years earlier, he had sent her a handwritten note thanking her for her comments about a building’s exterior lighting. She hoped he was well.

I picked up many other valuable professional lessons along the way. Once during a presentation, I referred to something I had done. Afterwards, David took me aside and gently chided me, reminding me that “there’s no ‘I’ in team.”

David’s passing feels like the end of an era – one in which America, despite its obvious flaws, stood for a greater good

On another occasion, while we were in a meeting, his assistant informed him that Donald Trump was on the line to discuss a potential project. David chose not to take the call. Surprised, I asked him why, and he explained that in New York, discerning which clients to avoid can be just as important as pursuing new ones.

A few months ago, I wrote about how Trump’s presidency might affect architecture and construction. At the time, there was still a naïve hope that he wouldn’t follow through on his more extreme promises – that the markets or more rational voices might prevail.

But less than three months into his term, it’s clear: he intends to do exactly what he spent the previous year campaigning on – disrupting the structure of institutions, government, and now the global trading system.

The recently announced tariffs will hit the construction industry and our profession hard. Months of uncertainty lie ahead. While we hope that trade agreements will be made and prices will stabilise, hope isn’t a plan.

For now, projects that were already difficult to finance with high interest rates will rapidly become unviable. In the short term, no one’s going to be breaking ground on anything unless they have to.

David’s passing feels like the end of an era – one in which America, despite its obvious flaws, stood for a greater good. He will be deeply missed, as will the optimism for the future that he so fully embodied.

>> Also read: Exempt from the chaos? What Trump’s tariff carve-out means for architects working in UK life sciences

>> Also read: Trump tariffs could make investors pause funding for major schemes, experts warn

Postscript

Chris Fogarty is co-founding principal of Fogarty Finger.

No comments yet