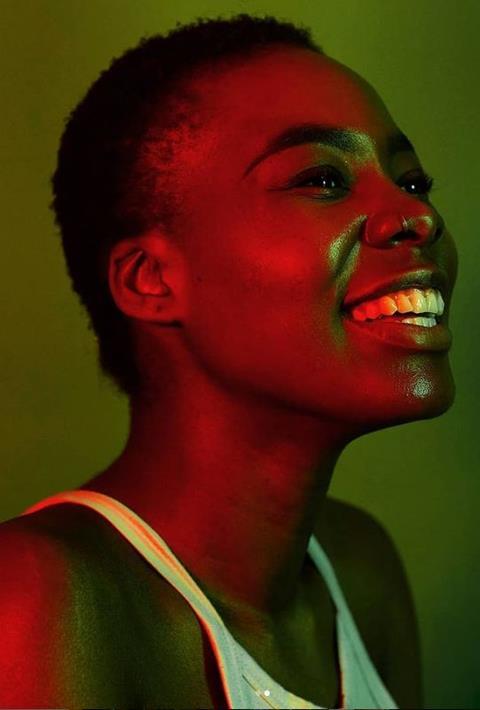

Kudzai Matsvai on how the recent far-right riots underline the urgent need to address systemic injustices within the architectural profession and wider built environment

A few weeks ago, unprecedented scenes unfolded as we witnessed our cities, towns, and streets terrorised by far-right hooligans. Fuelled by nothing but hate and misinformation, they wreaked havoc on the lives and livelihoods of Black, Brown, immigrant, and Muslim communities across the country for a week.

During that week, it was impossible to escape the race riots—whether on social media, the news, or even in daily conversations with family, friends, and colleagues. This inevitably led to broader discussions about systemic issues such as white supremacy, Islamophobia, and anti-immigration rhetoric, leaving many in the profession wondering, “What role, if any, do we play in all of this?”

Space is inherently political, given that our built environment is intended to equitably serve the needs of all the diverse individuals who occupy it. However, as I watched designated “safe” spaces—full of innocent people who came to this country seeking safety and a better life—being set alight, while white supremacist thugs controlled traffic based on skin colour and violently attacked unsuspecting citizens in the streets with impunity, I found myself grappling with the stark disconnect between intention and reality.

As we witness a nationwide return to a state of “normalcy,” many will be quick to forget these horrific events. However, as a profession, we cannot afford to adopt this amnesic approach and return to business as usual, because the gross inequities and hateful ideologies that emboldened those fascists to act did not disappear with the riots. They continue to exist in our cities, towns, neighbourhoods, streets, and even in our buildings. Therefore, it is paramount that we understand how the spaces we create are powerful sites of change that will either aid or oppose those inequities and ideologies moving forward.

>> Also read: Inclusion Emergency: ‘An emergency that we can no longer afford to ignore’

Spatial justice and equity in the built environment, particularly concerning issues like race and religion, regained relevance in architectural debates in the summer of 2020 following the brutal murder of George Floyd. Discussions on diversity quickly highlighted institutional shortcomings, with schools across the Global North admitting to failing those from racialised and underrepresented groups. Similarly, many practices released statements declaring commitments to being ‘anti-racist’, professing ‘allyship’, and pledging to ‘do better’. Yet, the recent violence that erupted across the country proved how little has changed.

In the wake of the riots, we must hold accountable those who were quick to speak in 2020. Their commitments and statements should not be dismissed as mere words but should instead be seen as pledges to act that go far beyond the passive ‘listening and learning’ strategies that became popular post-2020. It is also important to challenge those who are yet to speak, and more importantly, to act, on their continued silence and inaction.

As a profession, we must work to understand how factors like racism and Islamophobia impact people’s experiences of the built environment. The spaces we create directly and indirectly aid systems of oppression, as dominant ideologies like white supremacy and patriarchy are often embedded into their conception and manifest in their use. Without this vital comprehension, we are unable to fully understand the built environment and, therefore, unable to build a better world.

We must also strive to recognise that our professional environments often act as microcosms of the spaces we create, as the behaviours we perpetuate and normalise in the workplace are replicated, reproduced, and amplified in the built environment.

>> Also read: We need to address the prejudice and exploitation that underpin our national myths

Earlier this year, I interviewed people from marginalised groups working in the profession, and their experiences exposed deep-rooted inequities that remain unaddressed. Learning that Black built environment professionals still worry about certain hairstyles being viewed as unprofessional in the workplace, while Muslim people feel excluded from social events that often centre around alcohol, it became clear that the inability to recognise and cater to differences that we saw in our streets has roots in our work environments.

Architectural education is also in desperate need of challenge and change. It has never been just about gaining knowledge and skills; it also helps students to develop values and ideologies. Therefore, as we continue to grapple with systemic injustices on a global scale, these issues must also become central to the way we teach students to understand space.

We must strive to create architecture that directs people’s lives towards a future free from hate

In challenging education, it is also vital that we do not treat the violence we have just seen as an isolated incident, because riots have always been an integral part of Britain’s political and social landscape. In some of the most infamous riots of the past, including those that occurred in 1919 and 1981, racism and systemic abuses were once again underpinning factors. Racialised riots, and resistance to them, are central to the complex cartographies of Britishness.

As our architecture schools continue to reproduce and regurgitate the same Eurocentric, white-washed curricula that are largely to blame for our collective disconnect with these issues, they ignore these crucial cartographies of violence and resistance that are key to understanding the history and present state of Britain. To paraphrase Marcus Garvey, a people without a firm understanding of their past are like a tree with shallow roots: it can easily be uprooted when the winds are strong or the rains are heavy, and we are, indeed, in a period of strong winds and heavy rains.

What has once again become abundantly clear is that we are in desperate need of a radical reimagining of how we teach about, create, and occupy space. However, we cannot begin to imagine those futures while marginalised groups are still so underrepresented in our profession. A glance at the most recent ARB EDI survey will illuminate the state of emergency we are currently experiencing regarding diversity in the profession. So, how do we create diverse, inclusive, and equitable futures when the profession still does not reflect those values?

Japanese architect Tadao Ando once said, “I believe that the way people live can be directed a little by architecture.” As built environment professionals, we must strive to create architecture that directs people’s lives towards a future free from hate.

>> Also read: Why we need to talk about race and architecture

>> Also read: Inclusive building design helps clients demonstrate their commitment to people and planet

No comments yet