From school atlas to GPS, maps are the key to understanding ourselves, says Gillian Darley

Apart from a dictionary, the most important textbook of my school years was an atlas. It was, after all, the static 2D version of a globe and every classroom had one of those. The four corners of the world were presented in different colours, denoting colonial pasts alongside our own over-weaning imperial effort.

But even the nimblest publisher, even the most attuned government information agency, let alone this post-war stamp-collecting child turning into a politically aware young adult, could not keep up with all the adjustments through those decades. Not just the loss of pink on the page but names too, and concepts, from Iron Curtain and Eastern bloc to Common Market and European Union.

All that was in the hands of human agencies. But the mapping of the shifting, tormented natural world, the shorelines ravaged by the incursions of the sea, the disruption to contour lines after seismic activity and, now, the terrifying reality of rapid climate change, needs to move faster still.

For context, cultural historian Travis Elborough and map-maker Martin Brown have just published the Atlas of Vanishing Places, an intriguing list of locations around the world whose disappearance hinged on innumerable factors.

We may know Xanadu by name but we have only been able to visit the fragmentary ruins since 2011 for all it is now a World Heritage Site. Other places, like the River Fleet, still bowling along below our feet not far from where I write this, were simply forgotten while Port Royal, Jamaica, once “the roistering capital of the Caribbean” was decimated by an earthquake and tsunami in 1692.

Post-war Canvey Island in Essex could hardly match 17th-century buccaneering profligacy, but it was just as vulnerable to the whim of the ocean. In early 1953, devastating North Sea floods overwhelmed the Netherlands and then hit the east coast of England with terrible consequences and loss of life.

The tides and winds are, these days, confronted by the immense concrete seawall and yet, even in 2014, they remain unpredictable and there was almost another disaster. On the Ordnance Survey map the coastline remains intact thanks to those sea defences, but elsewhere the Essex landscape of estuaries, inlets and salt marsh is often left to fend for itself, the official term being “managed retreat” and the most conspicuous winners, ornithologists and walkers.

Ordnance Survey maps are, in their own right, historic documents of record. For immediate purposes we have instantaneous methods of reading a landscape, from Google Earth onwards. But back on those sheets (and Essex and Kent were the first counties to be surveyed, driven by the worry that Napoleon might arrive on our eastern shores by the shortest route) all manner of coded symbols are reminders of sites long gone, from gothic-lettered manors or abbeys to the runway lines of wartime airfields.

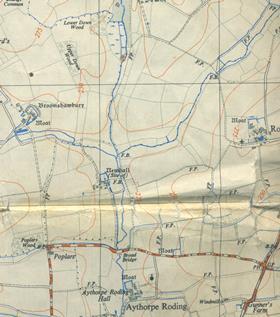

Elsewhere new introductions are added, such as a kind of peppering over the landscape, which turns out to denote landfill while they show rural constants – footpaths, watercourses, woods and, correct at the time of printing, public houses and phone boxes. Looking recently at the 1952 Ordnance Survey for my new book Excellent Essex, I noticed that where moats are common, in north-west and mid Essex, the cartographers show which ones still contained water, which not. Later editions dispense with that charming detail, a microscopic fragment from that atlas with which I began this piece.

But it suggests that if we can better comprehend our immediate surroundings, we might apply that principle to a wider world.

Postscript

Gillian Darley’s new book, Excellent Essex: In praise of England’s most misunderstood county, is out now from Old Street Publishing.

An exhibition on the history of maps, Talking Maps, is on at the Bodleian Library in Oxford until March 2020.

No comments yet