David Rudlin tries to pin down some slippery concepts

Twenty years ago the team at the Urban Task Force made the decision to replace the word “urban” with the word “quality” where they could in their report. The word urban, it was felt, had negative associations, but who was going to disagree with the notion of quality?

Twenty years later the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission has replaced the word “quality” with the word “beauty” and created an entirely different controversy. But they are still basically talking about the same thing.

Words matter, of course, and the suspicion of the architectural community was that the word “beauty” was code for “traditional” and was going to be a thinly veiled attack on contemporary design. That was certainly the case with the original Policy Exchange Report that gave birth to the commission which explicitly linked beauty with “traditional design”. This is why the spoof BD exposé of the workings of commission published on April 1 rang so true.

However the interim report, published last week, will confound the commission’s critics in waiting. Indeed the RIBA has already come out in favour. It is a perfectly sensible, well-argued analysis of why development in the UK falls so far short of what it could be, why ordinary people are so often dissatisfied with the results, why opposition is so strong and what we might do about all of this. Talking to Nicholas at last week’s launch, he made no apologies for referencing recent reports by Farrell, Letwin and Raynsford. There are some differences in emphasis but all of these reports, despite their very different origins, have come to similar conclusions. This is not repetition, it’s a growing consensus!

This is not repetition, it’s a growing consensus

The report starts by spending a little time justifying the word beauty. It recognises that in a time of housing crisis many people may not see beauty as the priority (you know who you are). It tackles head-on the criticisms that beauty means traditional design, is elitist and purely a subjective matter “in the eye of the beholder”.

It argues that just because a concept can’t be defined, doesn’t mean that it isn’t important. Beauty is like “truth” or “goodness” – it is hardwired into us and our relationship with the world around us. There are references to our love of beautiful old places but the report studiously refuses to engage in style wars and most of the examples cited are contemporary.

The report is also very good on assembling the research into why people oppose development: the notion of metathesiophobia being the fear of the new. It is realistic in acknowledging that good design will not, on its own, overcome concerns about the loss of green fields, pressure on infrastructure and more general worries about how communities cope with change.

It also provides a good review of the evidence of what people like and the fact that a majority of people accept the need for new housing. They also like access to nature, a supportive community, a sense of history and memory, well-made places, a walkable mix of uses and a sense of agency and stewardship. These are the components of beauty. It is just that they are much easier to find in old places than new ones.

People often don’t find out about a scheme until it’s too late - and then fight for years to oppose a decision that’s already been made. No wonder they feel excluded

The report goes on to make eight recommendations that the commission proposes to expand and develop in the second part of its work. Many of these – like building places not estates, collaborative planning, promoting a greater diversity of small house builders and better training and resourcing for planning departments – are sensible and nothing particularly new.

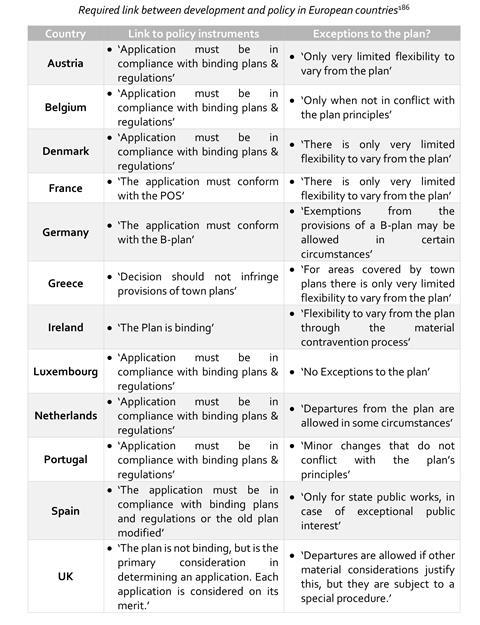

It also says sensible things about form-based design codes and the value of more spatial, less discretionally planning practices. (There is a useful table on page 60 - pictured - that shows that all European planning systems other than ours do this.) In Europe local people are engaged early in a proper debate about where housing should go and then, once the plan is fixed, discussions can focus on design. In Britain people often don’t find out about a scheme until it is already too late and then fight for years to oppose a decision that has already been made. No wonder they feel excluded.

But I am still left with a slightly uneasy feeling about building the report around the notion of beauty. As with “quality” one of the problems is that the word means so many different things that it creates the illusion of agreement while we all carry on talking about different things. Then there is the question of whether beauty can be a policy aim, or whether it is just what happens when we get things right?

The first recommendation suggests we should put “beauty first” in national planning policy alongside sustainable development (which is something else we struggle to define as the report accepts).

Then, having argued in the body of the report that beauty can’t be defined, the recommendation goes on to urge planning authorities to discover and define beauty “empirically through analysis and surveying of local views on objective criteria”.

This goes to the heart of the problem. While the report says many very sensible things I’m pretty sure the result of such an “empirical” process would not be pretty, let alone beautiful.

4 Readers' comments